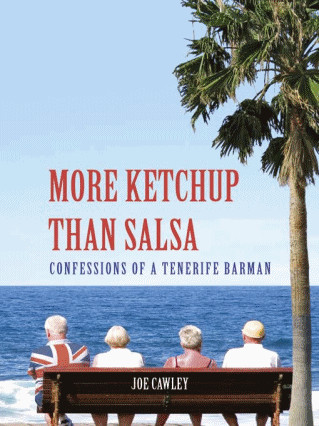

More Ketchup Than Salsa - Confessions of a Tenerife Barman

Read More Ketchup Than Salsa - Confessions of a Tenerife Barman Online

Authors: Joe Cawley

Tags: #Travel

More Ketchup Than Salsa

Confessions of a Tenerife Barman

Joe Cawley

MORE KETCHUP THAN SALSA

Copyright © Joe Cawley 2006

The right of Joe Cawley

to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

Printed and bound in Great Britain

ISBN 1 84024 501 8

ISBN 13: 978 1 84024 501 1

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

ONE

It was while holding aloft a not altogether pleasant-smelling mackerel that the decision was made. Blood dripping from a rabbit dangling overhead tinted the cold water from the fish and rolled down a white sleeve. The March rain hammered on the rotting tin roof high above the stall, and where there was more rot than metal, columns of water plunged onto the shuffling shoppers below. Their faces were drawn and bleak like a funeral cortège following the last remains of hope. From life they expected nothing – save a nice piece of cod at a knockdown price. Northern England in March. Northern England for most of the year, in fact. I was 28. There had to be more. I lowered the fish to eye level, ‘Is this my life?’

The fish said nothing but I already knew the answer.

I had worked on Bolton market for six months, forcing myself out of bed at 3.30 every morning to spend 11 hours knee-deep in guts and giblets, selling trays of dubious fish and chicken at three for a fiver. The freezing cold and the smell I had grown used to, but the pinched expressions of fellow passengers on the bus journey home still brought about a great deal of embarrassment. It couldn’t be denied, in the inverted language of market traders I was lemsy (smelly) from deelo (old) fish.

Word inversion was useful when you didn’t want customers to understand. ‘Tar attack!’ would have all the workers scuttling for higher ground onto splintered pallets or battered boxes of chicken thighs stacked at the back of the stall as a rat the size of a bulldog decided it was time for mayhem.

Originally dubbed ‘the poor man’s market’ in what was a working man’s town built on the prosperity of the local cotton mills, Bolton market was subsidised by the council to provide cheap food and clothing for low-income workers. (In a flourish of affluent delusion it has since been completely refurbished and modernised. The rats get to scamper around on fitted nylon carpets amid designer lighting franchises. An elegant coffee shop offering vanilla slices on dainty china now occupies the spot where once the best meat and potato pie sandwiches in Lancashire were messily consumed by fishy-fingered stall workers like me.)

It was an undemanding job both physically and mentally, which suited me fine. Stress was for the rich and hardworking, characteristics that were never going to be heading my way. That’s not to say that I was content. A string of menial jobs had taught me that contentment is not always found on the path of least resistance, but I had found myself meandering towards that monotonous British lifestyle of school–job–pension–coffin, and something needed to be done – fast.

I had grown bored with the same old stallholder banter – ‘We’re losing a lot of money, but we’re making a lot of friends,’ or ‘Oh yes, love, it

is

fresh, it

will

freeze.’

I was becoming less and less amused by the teasing of old ladies as they stood at the stall with purses wide open, names inadvertently displayed on their bus passes.

‘Hello, Mrs Jones. Fancy seeing you here.’

From beneath a crocheted hat the gaunt figure would try to force a vague recollection. ‘I… err…’

‘You remember me, don’t you, Mrs Jones? I used to come round your house for tea every Friday.’

‘I… I think I do. Yes, yes. Now I remember,’ she would say with a weak smile.

Even the daily competition to land a rabbit’s head in Duncan’s hood had lost its appeal. Duncan was a mentally retarded hulk who, although teased mercilessly by the market crew, was also well looked after by them. They gave him pocket money that he spent on

Beano

comics and Uncle Joe’s Mintballs, and made sure that no harm came to him from occasional gangs of skinheads that, for want of anything more constructive to do, would try to beat him senseless.

At six-foot-four, 18-stone, with no neck and an unappealing habit of walking around with his cheeks puffed out and his bottom lip investigating the underside of his nose, he was not what most able-sighted people would term ‘attractive’. If one of the workers did manage to score a rabbit he would charge at the victor, bellow obscenities and curse them with death threats until his attention was distracted by one of the girls. At this point all aggression would dissipate as he embellished the gurning with a damp pout. ‘Give us a kiss,’ he would demand in such a commanding voice that, were it not for his spectacular ugliness, would have been hard to refuse.

‘Hey, boss,’ I shouted, jerking my head back from the open box of chicken thighs. ‘You can’t sell this. It stinks.’ Pat continued pulling at the innards of a rabbit.

‘Dip it in tandoori and put it out as five for a fiver.’ I looked down at the poultry pieces glowing green.

‘No. I mean it really stinks. You’ll kill somebody with this.’ Pat lifted a red-stained sleeve above his shaved head and breathed in the blend of blood and body odour. His shoulders rose as his round torso filled with the sweet smell.

‘You’ve been here six months. Don’t start getting a jeffin’ conscience on me now,’ he grunted. He pointed the sharp end of a filleting knife towards me. ‘Get it sold. Anyway, the dead can’t complain.’

I dipped each piece in the bucket of rust-coloured spice then chucked them all in the waste bin when Pat turned his back to have a word with one of the girls, who had lost a false nail inside the rainbow trout she was gutting.

I decided that I should dispose of his lethal produce more permanently and wheeled the bin outside to the main rubbish collection point. The sky had given up on any attempts at clarity and had slipped into dull grey pyjamas, sucking the last remnants of colour from Ashburner Street. When had life turned grey? I asked myself. Where was the excitement, the glamour, the anticipation of things to come?

A voice answered: ‘Come on, Tinkerbell. There’s fourteen rabbits waiting for decapitation in here.’ Pat was poking his ruddy cheeks around the huge sliding doors, an ill-timed intrusion on the meaning of life.

A nine-to-five had never been a burning ambition. Neither for that matter was a five-till-four. I had long aspired to be a musician – well, a drummer at least. I’d answered the ad in my head and spent 14 years in an interminable interview.

Rock Star Wanted

Requirements: The ability to sit on your arse, make a lot of noise and become famous.

Remuneration: Unbelievable.

Perks: Aplenty.

But try as I might, I was always several beats behind stardom. A sporadic booking at Tintwistle Working Men’s Club was the closest I’d got to Wembley Stadium, which was more than 200 miles further up the pop ladder of success.

My battered old Pearl drum kit now gathered dust at the back of a garage in Compstall, while my life did the same at the back of a fish stall in Bolton. I desperately needed an out.

‘

Hola

!’ Two hands covered my eyes from behind.

‘I thought you weren’t back till tonight,’ I said and planted a kiss on Joy’s cheek. She’d just returned from a girls’ week in Tenerife.

‘I got the flight time mixed up so I thought I’d surprise you. You smell nice.’ She peeled a sliver of chicken skin off my neck.

‘Pat’s trying to offload some killer chicken. I’ve chucked it in the bin. You look well. Had a good time?’

‘Yeh, great. But listen, I’ve got some news. Big news. Meet me in the Ram’s after work.’ She winked and ran to the bus stop where the number 19 had just sprayed a line of rain-stained shoppers.

The rest of the afternoon passed just like any other. Terry came round to see if any of us had orders for him. ‘There’s a lovely brass table lamp I saw in Whitakers,’ said Julie, Pat’s wife. ‘Green glass shade, second floor, next to the clocks.’

‘Can you get me a clock, Terry? Nothing too fancy. Wooden perhaps. Something that’ll look nice above me kitchen door,’ asked Ruth interrupting the customer she was serving.

Debbie, Pat and Julie’s daughter, flapped her arms excitedly. ‘Oh, Terry, Terry, me Walkman’s bust. Get me a good one, will you? And don’t forget the batteries this time.’

Terry scribbled the orders on a scrap of paper. ‘Joe? Any more CDs?’

‘If you can get

Thrills ’N’ Pills And Bellyaches

, I’ll have that.’

‘Hey, if it’s pills you want, you only need to ask.’

‘No, it’s the new Happy Mondays CD.’

‘Oh, okay,’ he said, disappointed. ‘I’ll see what I can do. But if you

do

want pills,’ he tapped his nose conspiratorially, ‘I know a man.’

Terry returned at the end of the day, red-faced and panting. He dragged a large, leather holdall behind the stall.

‘Littlewoods are here,’ shouted Julie. We grouped around Terry who opened the bag and passed around the various items like Father Christmas on day release. Price tags were strung around the clock and table lamp and my CD still had the security tag attached.

‘I’ll be back on Saturday to settle up,’ he said and scuttled off into the crowd with the empty bag.

I continued to push out ‘tish’ at three for a fiver and mechanically joined in the banter. We wolf-whistled at passing girls and then shouted after them as they turned and blushed, ‘Not you love. Don’t flatter yourself.’ Monotony could be so cruel.

The Ram’s Head was not the obvious choice for a celebratory reunion but it was run by Leonard, the only landlord who would put up with the aroma of stale trout. A previous unsuccessful career in boxing had left him nasally advantaged when it came to our patronage.

There were half a dozen drinkers scattered about the perimeter of the high-vaulted room. Most sat alone. Their eyes tracked what little movement occurred beyond Leonard methodically drying glasses with an aged tea towel. A Jack Russell lay across the feet of one man. It yawned at the lack of antagonists while its master carefully rolled a cigarette as if in slow motion.

Brass wall lights topped with cocked green shades cast the room in a sickly pallor, throwing sallow circles of light onto the once-white wallpaper, now jaundiced through decades of low-grade tobacco.

The only sounds were phlegmatic coughs and the deranged melody of a fruit machine happy to have found a friend. Joy was feeding it 50-pence pieces with one hand, jabbing at the nudge buttons with the other. Her tan had attracted the attention of two investment advisers dressed in no-brand tracksuits, who were teaching her about consecutive bells and lemons. Lessons in slot machine skills she certainly did not need.

‘Pint and a half please.’

‘Joy’s at it again.’ Leonard smiled a toothless smile and nodded at the machine.

‘No stopping her, I’m afraid. She insists it’ll pay off one day.’

I carried the glasses carefully across the threadbare carpet and blew on the back of her neck. ‘You winning?’

‘Nearly. Have you got any fifties? I think it’ll hold on two bars.’ The two lads peered inside the machine trying to see if was worth risking their beer money.

‘Come on.’ I motioned to a table under a window. A karaoke poster written in yellow marker pen obscured most of the outside view which would have been of the damp remnants of Bolton’s first ever bicycle shop.

‘So what’s this great idea then? You give all your money to me and I stop it disappearing inside those stupid machines?’

She took a sip and raised one eyebrow. ‘You’re gonna like it.’ She paused to take another sip then smiled again. I smiled back. ‘So come on then.’

I’d known Joy ever since she’d pushed me backwards off the top of the slide at nursery school. She was an experimental child but compassionate with it. As soon as my head had hit the floor she slid down and ran around to peer in my face. ‘You dead?’ she asked. I managed to smile crookedly as Miss Cornchurch dragged her off by the arm before I passed out.

But I took solace in the fact that I was not the only one bullied by Joy. In fact, she was so impressed by my not dying that she took on the role of protector and regularly pushed other kids off the slide if I wanted to have a go. She also insisted that I push

her

off, as she was curious to see what it felt like to fall so far. I declined the offer.

As pre-teens we had only once stepped over the line of platonic friendship. It was Saturday night and her parents had left us playing Buckaroo while a romantic western flickered in the background. Joy’s attention was diverted from the kicking mule by a passionate scene involving a feisty cowgirl and cowboy.

‘Kiss me like that,’ she commanded and pulled my face against hers. I remember the taste of liquorice toffees and wondered if this is what she tasted like to herself all the time. We remained eye-to-eye for about a minute until, unimpressed, Joy pulled away and silently placed another bucket on the donkey’s backside. Romance didn’t surface again for a long time although we both maintained a mutual disrespect for each other’s juvenile

amour

s.

Although in different classes at comprehensive school, we would still hang around with each other during most lunch breaks and after school, plotting horrific revenge on the teachers that had dared to reprimand us. I was usually no more than an accessory, but due to my pubescent lanky stature I had taken over the mantle of protector. And boy, did she need it. A cheeky smile and sparkling eyes could redeem her of most crimes but there were times when physical intervention was unavoidable.

We finally became an item after an unplanned holiday together. Joy’s boyfriend had dumped her just days before departure, accusing her of spending more time with me than with him. It all came to a head outside the Dog and Partridge in Hazel Grove, when I was invited to what her boyfriend thought was going to be a cosy tête-à-tête, but which turned out to be a tête-à-tête-à-tête.

On a campsite in southern France, fuelled by too much alcohol and exposure to naked flesh, intimacy was inevitable. The holiday romance continued after we returned home and still did three years later inside a dingy pub in Bolton.

‘How do you fancy moving to Tenerife?’ Joy peered over the rim of her glass. Her eyes searched mine.

‘Uh… why?’

‘We’ve been offered the chance to run a bar, only it needs two couples to run it, so I said I was married.’