Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting (2 page)

Read Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting Online

Authors: W. Scott Poole

Master narratives are, by definition, lies and untruths. This is why we need to study monsters. They are the things hiding in history’s dark places, the silences that scream if you listen closely enough. Cultural critic Greil Marcus writes that “parts of history, because they don’t fit the story a people wants to tell itself, survive only as haunts and fairy tales, accessible only as specters and spooks.” The secrets and the lies, and perhaps most importantly the victims of history, are in those stories of monsters, those dark places waiting to be explored. These places became dark in the first place because they did not fit the historical story we wanted to tell ourselves.

3

So, I am wondering if maybe the movie

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre

can explicate issues that a full-scale study of Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal policy cannot. Its lead character, Leatherface, certainly makes an impression, and his house of horrors has a lot to tell us about the American frontier. I am wondering if Frankenstein’s monster might offer us a new way to grasp the horrors of scientific racism or if Dracula can teach us something about the early twentieth-century Red Scare.

I do not want to be misunderstood here at the beginning. This is not an effort to use some horrific examples from fantasy literature and film to illustrate important truths about American history. Instead, I am seeking to read the monster as what theorist Slavoj Žižek refers to as “a fantasy scenario that obfuscates the true horror of the situation.” The monster reifies very real incidents, true horrors, true monsters. This is why they are always complicated and inherently sophisticated. The monster has its tentacles wrapped around the foundations of American history, draws its life from ideological efforts to marginalize the weak and normalize the powerful, to suppress struggles for class, racial, and sexual liberation, to transform the “American Way of Life” into a weapon of empire.

4

The reader should also be aware that the author believes in monsters. They are real. Before you shut this book and write it off as Fortean propaganda, know that I do not see myself as a poor man’s Mulder from the television show

The X-Files

, here to tell you that the truth is out there. But before we start talking about “monsters as metaphors,” let’s examine that construction a bit and you will see why I would rather just assert my belief in monsters.

5

The problem is in the concept of metaphor itself. “My love is like a red, red rose” is metaphorical language expressing a desire to sing the beauty of the beloved (and to get laid by the beloved). But really, who cares? Metaphors can be beautiful, inexact, or just plain silly but, regardless, nobody takes them seriously. The phrase “just a metaphor” sounds suspiciously to me like “just a waste of time.”

Lots of books are out there about monsters as metaphors for this or that social or psychological process. I do not think this approach works well when it comes to history. In American history the monsters are real. The metaphors of the American experience are ideas hardwired to historical action rather than interesting word pictures. If you stick with me on the path, I will explain more. Just be forewarned—I take my monsters seriously.

I do not, however, take traditional historical chronologies seriously. Although this book engages in a chronological analysis of a kind, it also ignores some of the basic conventions of historical narrative. We will move back and forth between periods, and listen to voices in the seventeenth century and the twentieth century at the same time, generally mucking up any effort to read the American experience as a linear, and thus progressive, march through time. This is because I hope to trace the ways American monsters form a systemic network, or perhaps a cultural echo chamber, rather than something like a time line.

It is also because I believe that seeing history as a stark glacial formation of dates and facts leads to viewing history as “dead” and definitively “in the past.” This, in turn, can make way for the tendency to monumentalize those events, to invest them with the immovable power of marble statues. History as memorizable event becomes at once detached from the present and the embodiment of a profoundly conservative pedagogy, markers of boundaries and parameters that can never be changed. History then becomes dead cultural weight the present must carry on its back rather than living events in conversation and debate. On the other hand, refusing to accept the idea that history is dead things on a time line frees us from the incredibly assertive arrogance of the past, its lifeless yet grasping hand. If we do otherwise, we will feel that hand, cold and brutal, holding us tight and not letting us go.

6

And so we are going to pass a long night together. If you and I make it until morning and find our way out of this dark wood, we will not see American history the same way ever again. Seeing America through its monsters offers a new perspective on old questions. It allows us to look into the shadows, to rifle through those trunks in the attic we have been warned to leave alone. Not all of our myths will make it out of here alive.

I hope one of the first victims, by the way, is that loudmouth “American exceptionalism.” This unfortunate philosophy has it that America has always been the innocent abroad, the new nation who teaches the world democracy. This sophomoric notion of world history since 1776 presents the United States as Little Red Riding Hood, setting off on the forest path of democracy and economic liberalism. A hard look at American history raises questions about whether the American nation has been the innocent in the woods or that other, more feral figure in the forest (Oh grandma, what hairy arms you have!).

So let our midnight ride begin. We will start by figuring out the way monster narratives work and what others have said about them, and hardly catch our breath before we plunge into colonial America’s world of witches and wonders. Creatures of scientific nightmare will haunt us in the nineteenth century as we meet Hawthorne and Poe, two old hands at navigating this eldritch wood. The twentieth century seems to open out into a new vista, but we only briefly see some sunlight, and we are back in the dark wood again, hiding from escaped mental patients and seeing strange lights in the sky. We will begin to dream of home and yet also wonder if it is all that safe a place after all before we get chased by creatures of the night eager to chew on us and suck us dry.

I hope you have snuggled back into your favorite reading chair and assured yourself that the world, or at least your little corner of it, is a safe place. Unfortunately for you, I propose to show you that it is not. You are implicated in a violent history, a historical landscape where monsters walk. Like it or not, you are part of the story, and it is not a romantic comedy or a melodrama. You are the main character in this terror-filled little tale.

At about this point, the Crypt Keeper would unloose a demonical laugh, both at the twisted subject matter the audience was about to read and the twisted nature of the audience who wanted to read it. Vampira would give her adolescent audience a bloodcurdling scream to announce that the grisly fun could begin. I cannot pull off that laugh, and in print no one can hear you scream. So, without further ado, let us bring on the night.

—

Herman Melville,

Moby-Dick

Joey: The demons, the demons!

Priest: Demons? Demons aren’t real, they are only parables, metaphors.

(Church door explodes and Pinhead stands threateningly in the door.)

Joey: (finger pointing at the monster)

Then what the fuck is that!

Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth

N

ovelist F. Scott Fitzgerald’s arrival at the MGM commissary followed fast on a night of humiliation. The author of

The

Great Gatsby

had embarrassed himself, in his mind irredeemably, at a party thrown the previous evening by acclaimed producer Irving Thalberg and actress Norma Shearer. Fitzgerald drank too much and launched into a long and embarrassing rendition of “In America we have the dog/and he’s a man’s best friend,” the kind of song, an observer noted, that “might have seemed amusing if one were very drunk and still in one’s freshman year at College.” Fellow screenwriter Dwight Taylor quickly saw that Fitzgerald’s erstwhile audience was not amused. Tolerant smiles turned

to a low and ominous hiss of disapproval. In the sober light of dawn, Fitzgerald felt his humiliation compounded by the fear that Thalberg would fire him for his indiscretion, cutting off his income at a time when he was desperate for funds needed to pay for his wife Zelda’s care at a sanitarium.

1

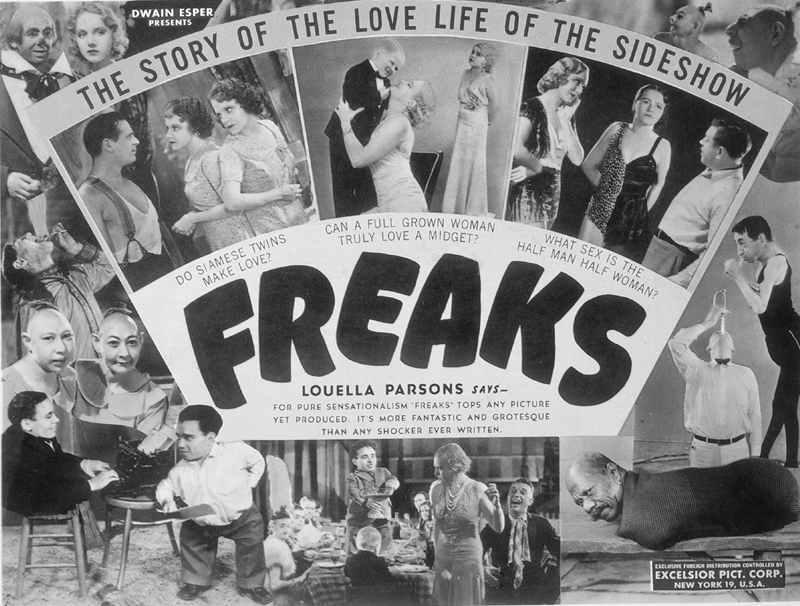

The following day, Fitzgerald planned on a hangover recovery lunch with Taylor. Neither seemed aware that they would share the commissary with the cast of the new Tod Browning production

Freaks

. Browning, coming off his wildly successful production of

Dracula

in 1931, enlisted actual sideshow performers to be the stars of his controversial project. The cast of the film that came to work on the MGM lot included midgets, a small boy with simian features and gait, fully joined Siamese twins, heavily tattooed persons of uncertain gender, and a so-called pinhead, a microcephalic with a tapering cranium and large, heavy jaw.

Almost as soon as Fitzgerald took a seat, Siamese twins known as the Hilton sisters joined him at his table, sitting down on a single stool. Holding a menu in their hands, one of the twin’s heads asked the other “what are you thinking of having?” Fitzgerald, already under the weather after his previous night’s adventures, became immediately and violently ill. “Scott turned pea green” remembered Taylor, “and rushed for the great outdoors.”

2

Fitzgerald was far from the last person to have a bad experience with

Freaks

. America did not fall in love with the tale’s twisted love story that ends in the betrayal of the freaks by a “normal,” a betrayal that the freaks answer with a horrible and unforgettable revenge. In fact, the first audiences shrieked, vomited, or simply left the theater.

The preview of the film on December 16, 1931, can only be described as a complete and utter disaster. One observer noted that disgusted audience members not only left the theater, they actually ran to get away from the film. In response to audience reaction, Browning cut

Freak

s by more than half an hour. Despite significant changes, the film still managed to anger and disgust film reviewers as well as religious and civic leaders. Louis B. Mayer, head of MGM, later sold Browning’s ode to the sideshow in hopes that he and his company would no longer have any connection to it.

Freaks

went underground for thirty years until it appeared again in 1962 at the Cannes Film Festival and soon became a permanent feature on the art house circuit.

3

The response to

Freaks

would seem to suggest that Americans have no room for the monster. As the United States faced an economic crisis in the 1930s that appeared to represent the failure and collapse of the American experiment, the portrayal of such disturbing topics as physical abnormality, torture, and ritual murder hardly seemed the tonic the movie-going public needed. The failure of

Freaks

perhaps signaled the public’s desire to see more of the kinds of films that Mayer and MGM had become famous for, namely, light romantic fare featuring actors who embodied Mayer’s fascination with blonde Anglos of perfect bodily proportions.

4

1933 Freaks featuring the Hilton Sisters

Yet this was not the case. The biggest cinematic heroes of the decade before the Second World War, purely in terms of the money they made for their studio, included a foreign aristocrat who drank the blood of his victims in a film with a clear sexual (both homo and hetero) subtext, and a monstrosity knitted together of cadavers and given, by his half-mad creator, the brain of an executed murderer. At the beginning of the next decade, Hollywood’s biggest commercial draws would include a man transformed into a ravening beast through a satanic curse and a raft of scientists delving into forbidden knowledge.

Freaks

flopped, and yet these other monstrosities shambled, howled, and slithered their way into America’s hearts.