Mithridates the Great (23 page)

Even if the case is hopeless, Justin has Mithridates declaiming, a true man will draw his sword against robbers, if only to achieve some measure of revenge. Yet Pontus could not only revenge itself against Rome, but follow the examples of the Gauls and Hannibal and bring the city to its knees. Nor was it a question of whether to go to war with Rome – merely a question of whether the time was currently right; Rome being Rome, war was inevitable at some point, as past Roman conduct had proven. ‘Their founders, as they themselves claimed, were suckled by the teats of a wolf, so the whole race has the disposition of wolves, insatiable in their lust for blood and tyranny, desperately hungry for wealth’.

Rome had enslaved even its native land of Italy and was even now making war on its own peoples. As proof, the king pointed to his entourage, which included Romans of noble descent who had taken refuge with him from the violence of their own city. (These were the men sent by Sertorius, one of whom bore the renowned name of Marius. This Marius was Sertorius’ candidate for governor of Asia if Mithridates succeeded in ‘liberating’ the province. It has also been suggested that enough disaffected Fimbrians and other deserters had joined the Pontic side to produce an Italian-style legion.) Mithridates pointed to the strength of Pontus, its conquests on the Black Sea, and his own lineage as a descendant of Xerxes and Cyrus, and promised his men that he would lead them personally to victory.

2

The chronology of what happened next is uncertain.

3

The most probable scenario has Mithridates retaking control of Paphlagonia at the end of 74 BC, before the Roman consuls arrived in Asia Minor in the following year. This aggressive move by Mithridates would have given the consuls a clear idea of what they were in for; in fact, the young and energetic Julius Caesar had already interrupted his studies at Rhodes and taken over organizing the defence of Bithynia on his own authority. The manner in which the consuls went on to a

full war footing from the moment of their arrival certainly suggests that Mithridates had already made his intentions clear. Furthermore, the Pontic invasion force that descended on Bithynia in the spring of 73 BC spring took only nine days to arrive, which suggests that it either moved by forced marches, or from nearby Paphlagonia.

Mithridates seemed to be following the same path as he had taken when he swept down from the mountains in 87 BC in the wake of the defeated Nicomedes and Aquillius, but the situation in 73 BC was significantly different. Lucullus, to the south, would probably be able to pull together a fully-fledged Roman army of four legions. Admittedly, the core of that army would be the Fimbrians. Surly, disaffected, and openly longing for their discharge papers, they were, nevertheless, veteran Roman legionaries, tough and deadly once they could be persuaded to fight. Cotta, in Bithynia, was the easier target, as he had few Roman troops under his command and was a somewhat inept commander himself, as Mithridates’ spies in the Roman camp had undoubtedly informed their king. Furthermore, Mithridates was uncertain exactly how the Romans to his south were deployed, but he knew exactly how to get at Cotta. Therefore he sent his general Diophantes south with orders to hold the passes along the Halys, whilst he aimed to crush Cotta before Lucullus could swing into action.

4

With Cotta gone, perhaps Asia would rise again, allowing a vastly strengthened Mithridates to swing south with his full force, defeat Lucullus, and claim suzerainty once more over the full area of Asia Minor.

Chalcedon

The Roman operation was in many ways the mirror image of what Mithridates had in mind. Like Diophantes, Cotta was to try to stop the main enemy push, whilst the stronger part of their forces under Lucullus pushed into the enemy heartland, and then swung back to defeat the by-now hopefully demoralized and weakened main army. Lucullus, however, had first to whip the Fimbrians into shape, train up his raw levies and gather together the legions which had previously been deployed against the pirates in Cilicia. It is not surprising then that Mithridates’ version of the plan, carried out by well-trained and prepared troops, came into operation first and forced Lucullus to change course.

Most of Bithynia welcomed Mithridates back with open arms. This was unsurprising since the province was still outraged by its first experience of Roman rule. Even in the cities of the province of Asia there was unrest, even

though these cities had also experienced the weight of Roman vengeance. Heraclea tried hard to maintain neutrality, but Mithridates arranged the killing of Roman tax collectors and his popularity soared. The city government was forced to hand over ships and money to help with the Pontic war effort and to admit a Pontic garrison within its walls.

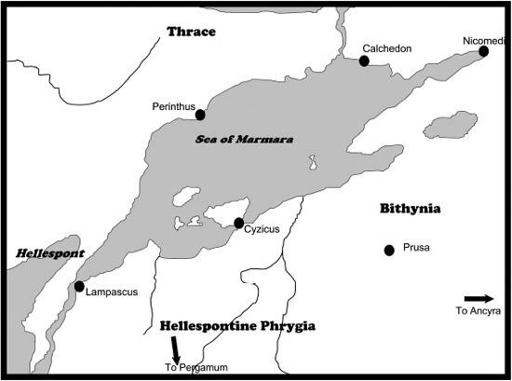

Cotta retreated to Chalcedon, where he had the Roman fleet at his back, and sent urgent messages to Lucullus to the effect that the invasion of southern Pontus could wait until the Pontic invasion of Bithynia had been dealt with. These messages became even more strident when Cotta unwisely allowed Nudus, his naval prefect, to take the field against Mithridates. Nudus located his men in fortified positions outside the city, but, like Murena before him, was utterly taken aback by the speed and professionalism with which the Pontic army swept over his defences.

The Roman force fell back to the city, but it was an untidy retreat with the rearguard already overwhelmed. After the Pontic archers had made the most of the tight-packed targets struggling to get into the city gates, the Pontic infantry charged. The city’s defenders had no choice but to drop the portcullis to prevent Mithridates’ men from getting inside. This left a large portion of the Roman force trapped outside the walls. Nudus and some of his officers were pulled over the ramparts by rope, but from there they could only watch as the rest of their force, some 3,000 men, was cut down.

Mithridates energetically followed up his success with a combined land and sea assault on the harbour. An advance guard of Bastarnae (this Danubian tribe, was called by Appian ‘the bravest people of all’), managed to break the long chain of bronze that guarded the harbour entrance, and the Pontic fleet sailed in. The Romans lost four warships before their resistance collapsed. Then the defenders on the walls of Chalcedon could only watch in horror as their enemies calmly took control of sixty warships, the entire Roman naval strength east of Athens, and towed the ships away for later recommissioning as part of the Pontic navy. In the entire battle, Mithridates lost twenty men, those being from the Bastarnae assault force.

With Cotta bereft of his army and his fleet, his local support melted away. Nicaea, Lampsacus, Nicomedia and Apameia, all major cities in the region, either fell to Mithridates or opened their gates to him. Only the nearby city of Cyzicus held to the Roman cause, perhaps embittered towards Mithridates because some 3,000 of their citizens had died fighting at Chalcedon. Cotta’s only hope was Lucullus, but the question was whether Lucullus would come. Mithridates former general, Archelaus, was now firmly and literally in the

Roman camp, either because the suspicions of Mithridates had driven him there, or because those suspicions were justified in the first place. Archelaus argued that Diophantes and his army guarding the southern passes could easily be defeated, and thereafter, Pontus would be defenceless. This was a tempting option, not least because a Roman army in the heretofore unplundered Pontic heartland could get very rich before Mithridates returned from Bithynia to defend his kingdom. Nevertheless Lucullus put saving Cotta first.

Finding the enemy

For once, Mithridates’ excellent intelligence network seems to have failed him. He ordered Diophantes to send out probing raids to try to find Lucullus, and sent another general, Eumachus, plundering across Phrygia and Psidia to see what reaction this would draw. After initial success, Eumachus did indeed encounter serious opposition –s but not from the Romans. Mithridates’ vindictive purge of the Galatian leadership during the first Mithridatic war had sufficiently thinned the field for a single Galatian, Deiotarus, to become king of the hitherto disunited country. Deiotarus knew that one of the best ways to unite his people under his rule was to lead them against a foreign enemy, and no other foreigner was as well-hated by the Galatians as Mithridates. Accordingly, he attacked Eumachus and duly sent the somewhat battered general back to Bithynia to report that, despite the absence of Lucullus, Phrygia was emphatically in enemy hands.

Eventually Lucullus was located and scouts reported him to be moving north up the valley of the River Sangarius to confront Mithridates. Consequently, Diophantes was released from garrison duty to take his men raiding the new Roman conquests in Cilicia and Isauria, and a large force was sent under Marius, the Sertorian ‘governor’ of the province of Asia, to confront the Romans. The two sides met in the Bithynian lowlands between Nicaea and Prusias, at a place called Otryae, for the most puzzling confrontation of the war.

It appears that

L

ucullus had been expecting to meet a small detachment guarding the Pontic rear and probing for his whereabouts. He was nonplussed when he found that the enemy force was almost as large as his own contingent of 30,000 men, and confident enough to offer battle.

T

his challenge, unless he was to lose all credibility with his unruly legions, Lucullus had to accept. The battle lines were drawn up and there followed an odd delay. Perhaps Lucullus was reluctant to engage in case his army received a severe mauling

even before it had encountered the main Mithridatic force. And it has been credibly suggested that the Sertorians were confidently waiting for the Fimbrians to come over to their side. They had, after all, been sent out whilst leaders of the faction of Sertorius had been ruling Rome, and should still be sympathetic to that cause. However, for the moment, it appeared that the Fimbrians were giving Lucullus the benefit of the doubt and they stayed firm in their loyalty to their general.

Thereafter, proceedings were interrupted by a strange event. In the words of Plutarch ‘without warning the skies opened, and a large glowing object fell to the ground between the two armies. It was the size of a substantial barrel and glowed like molten silver’.

5

Uncertain what to make of this strange and undoubtedly-supernatural prodigy, the two armies withdrew from contact and did not re-engage thereafter.

This reticence was partly due to the fact that Lucullus, astonished by the size of the detachment that Mithridates had sent against him, decided to make serious enquiries about the size of the Pontic force. When he established that it numbered just less than 300,000, the Roman general determined on a new strategy. Even the resources of Pontus would be stretched to keep that many fed and Mithridates had to transport the food to them. The way to defeat so large an army was memorably described by Lucullus as ‘stamping on its stomach’. In fact the Pontic army numbered about 140,000 infantry and about another 20,000 cavalry. But a cavalryman is effectively a man and a horse, giving the combined pair a tremendous appetite, and though the rest of the 300,000 were camp followers, these had to eat too.

6

Apart from supplies and whatever nefarious plans the Romans were cooking up against him, Mithridates had other worries. It was becoming clear that, despite the Pontic success at Chalcedon, the occupation of Asia Minor was not going to be the triumphal procession of 87 BC. Young Julius Caesar was keeping much of the western coast loyal to Rome, and the Asian cities, with their brutal experience of Roman resilience and vindictiveness, would not commit to the Pontic side again unless victory seemed certain.

The siege of Cyzicus

To encourage the others, Mithridates looked for a recalcitrant city to make an example of, and chose nearby Cyzicus. There were strategic as well as political reasons for this. It was becoming probable that the fate of Asia Minor would largely be determined by a single confrontation, rather as the Romans had broken the power of the Seleucids in 190 BC at the Battle of

Magnesia. The Pontic king would undoubtedly have paid careful attention to what was required to prevent the Romans enjoying a similar victory on the forthcoming occasion. Pontus had a good army that hugely outnumbered Lucullus, and their cavalry was vastly superior. In the Bithynian lowlands, there would be none of the cramped conditions experienced at Chaeronea, and if Lucullus did as Sulla had done and dug in, Mithridates would simply leave the battlefield and go elsewhere. In short, Mithridates was prepared to play a waiting game if need be. It had probably also occurred to him that Lucullus, too, would stand off from a crucial battle until lack of supplies had

worn down the Pontic army, and he was determined that this lack of supplies would not happen. Mithridates’ current supply base was at Lampsacus, where the harbour was good enough to shelter his fleet, but was totally unequipped to handle the tons of war materiel required by his huge army. In fact, by detailed questioning of prisoners, Lucullus had satisfied himself that the entire Pontic army was virtually living from hand-to-mouth, with just four days of reserves.