Mithridates the Great (15 page)

The situation in Athens was desperate. Three times Archelaus had tried to get supplies to the city’s starving people, and each time his plans had been betrayed from within. After his second attempt failed, Archelaus suspected what was happening. To confirm his suspicions, he ordered, in the strictest secrecy, an attack on the Roman lines at the same time as a further push was to be made to get supplies to the Athenians. Sure enough, the Romans were away attacking the Pontic supply train when Archelaus’ attack took place. The Romans returned to find that the defenders of the Piraeus had made a bonfire of their siege weapons for them to cook their captured food on.

To make sure the famine within Athens was effective, Sulla had built forts and surrounded the city with a ditch to make sure that no-one got out. Consequently, hunger had weakened the defenders to the point where rumours of cannibalism abounded, and the walls were no longer adequately defended.

3

Hearing that there were no longer any guards on a particularly vulnerable section of the walls, Sulla first reconnoitred the spot personally to ensure this was not another diabolical Pontic trap, and then, on 1 March 86 BC, he sent a storming party over the walls. Plutarch describes what followed:

At around midnight, Sulla entered the breach, accompanied by the triumphant howl of an army turned loose to rape and slaughter. They swept through the streets with naked swords ... even without mentioning what happened in the rest of the city, the blood from the Agora spread across the area of the Ceramicus, poured under the Double Gate and ran through the gutters of the suburbs.

4

Eventually, the extent of the slaughter turned even Sulla’s stomach and he ordered an end to the killing. In a reference to the city’s glorious past, he magnanimously announced ‘I shall spare the living for the sake of the dead’, though one Greek historian bitterly remarked ‘by then there were few enough

living to spare’. Ariston and his cronies took refuge in the Acropolis, the ancient citadel of Athens. The Romans saw no point in losing lives in storming the place, and waited until thirst did their work for them. Ironically, an hour after Ariston surrendered, a squall descended on the hill and deluged it with water whilst the Romans were busily helping themselves to the Athenian gold and silver reserves stored within.

With Roman morale boosted, the attack on the Piraeus resumed with renewed fury. Catapults, siege towers and rams hit the walls in a coordinated wave, while a rain of arrows and javelins sought to clear the walls of defenders. The Romans smashed through the lunette, only to discover that Archelaus had built another lunette behind that, and others in sequence almost the entire way back to the dockyards. There was, however, a maniacal determination behind the Roman attack which forced the slightly-stunned Pontics to give ground despite themselves. Finally, Archelaus pulled back right to the Munychia, the central harbour of Piraeus, which, for the time being, was out of the Romans’ reach.

In fact, by this time Archelaus was only in the Piraeus at all because the Romans were so determined to take casualties by smashing themselves against its walls. The Pontic general was well aware that the entire bloody episode at Athens was something of a diversion from the main contest. Mithridates’ main army had now arrived. Under the command of Arcathias, a son of Mithridates, this huge force (estimated in the Roman sources at 100,000 men, 10,000 horse and 90 scythed chariots) had effortlessly swept the Roman legions of Macedonia aside, conquered the province, and hurried down to Greece. Even given the enthusiasm with which Roman historians over-estimated the size of Asiatic armies, there is no doubt that this was a formidable force. Archelaus had been a distraction to keep the Romans from interfering whilst the army of conquest arrived. Now it was here, Archelaus embarked his troops and sailed to join the main army, probably as he had always intended.

The Roman army took possession of the Piraeus and Sulla, in a fit of evil temper, ordered the burning of the famed Athenian dockyards. Then, like the Pontic army, he abandoned Athens and the Piraeus, and took his men to Boeotia where the decisive battles for Greece would be fought.

There was good reason why Sulla, having fought so hard for possession of Attica, was in a hurry to leave the place. The environs of Athens had been host to a Roman army for the better part of a year, and a Roman army which was not getting supplies from home at that. Consequently almost anything edible

that grew or walked had ended up in the bellies of Sulla’s soldiers. Athens was certainly not going to supply any more food, so, unless Lucullus was able to eventually return with sufficient ships to beak the Pontic stranglehold on the sea, Sulla had to move. Boeotia was flatter and much better suited to cavalry in which the Mithridatic army had overwhelming superiority. Even so, facing the enemy there was better than remaining in Attica and waiting for the Pontics to take up a strong position and wait until hunger forced the Romans to attack it. Besides, Sulla had achieved his objective and knocked Athens out of the war – so thoroughly that it would be a generation before the place achieved even a shadow of its former glory.

There was a final reason for moving out, and that was the significant Roman force in Thessaly under the legate Hortensius – quite probably the remnant of the Roman force in Macedonia which had fought its way southward.

*

Hortensius had some six thousand men under his command and Sulla was desperate enough for the extra manpower to run considerable risks, especially given the other pressing reasons for leaving Athens already mentioned. Hortensius had his own problems, as the Pontic vanguard was pressing him hard. Using native guides, he made his trip laboriously through the mountains, taking care never to cover ground wide or flat enough for the Pontic superiority in numbers to be brought to bear. Fighting by day and retreating by night, the small Roman force eventually joined with Sulla’s on a defensible hill on the Plain of Elatea, near the opening to the Boeotian plain.

Even united, the Roman forces were hardly sufficient to strike terror into Pontic hearts, numbering some 15,000 foot and well under 2,000 cavalry. On the other hand, every one of these men was a hard-bitten veteran, and in ancient warfare quality counted for much more than quantity. It was only possible to bring a certain number of men face-to-face in a battle line and, because the Romans fought more or less shoulder-to-shoulder, it was not uncommon for them to have local superiority over more numerous enemies who fought in more dispersed formations.

Mithridates’ son, Arcathias, had died at some point in the march into Greece, and the army fell under the command of one Taxiles until Archelaus took over once the Pontics joined forces at Thermopylae. Archelaus was unable to bring the Romans to battle. His men, deployed in battle order, almost covered the plain – a splendidly-armoured, multi national force, with the chariots and cavalry dashing about in front of the main army. This so intimidated the Romans that they refused Sulla’s

demands that they go out and fight. Sulla responded with his usual tactic of giving the men hard labour that made fighting seem the easier option. While the Romans were making up their minds what to do, Archelaus employed his army in devastating the towns and cities about him. He had no inhibitions about this, as they had changed sides to Rome when Sulla had arrived in the country.

The first sign that the Romans were girding for battle came when Archelaus sent a unit called the Brazen Shields to take a hilltop fortress, and the Romans, urged on by Sulla, managed to beat the Pontic unit to take possession of the position. Thereafter, when the Pontic force descended on Chaeronea, a Roman detachment managed to get in ahead of it and garrison the town against attack.

The move on Chaeronea gave an indication of Archelaus’ thinking. Sulla was secure on his hill and had plenty of fresh water (indeed, one of the tasks he had given his legionaries as a cure for timidity had been to divert a nearby river to a more favourable course). However, 18,000 men and horses needed a lot of feeding but Sulla, without enough cavalry to protect his men, could not let them forage for supplies. The Roman supply lines ran through Chaeronea – block these and the Romans could be starved into battle.

Sulla in his turn was more than ready to transfer operations south to Chaeronea. This fortress town was on a massif, the highest point of which was Mount Thurium. With Mount Hedylium opposite to the north and the river valley of the Cephisus between, Chaeronea controlled access to the northern plain of Boeotia. Because of its strategic position it had seen a major battle once already in its chequered history, in 338 BC when Philip II of Macedon had conquered the Thebans. Its position meant that Chaeronea needed to be defended for its own sake, but, as Sulla’s advance party would have made clear, the rocky plain between the mountains was much less suitable for the manoeuvring of large bodies of men and cavalry – a situation which favoured the Romans.

Nevertheless, having got himself into the northern part of the plain, Archelaus had either to get through the Roman army which now blocked his passage to the south or abandon the current position altogether and make his way into Boeotia by a completely different route, an option which involved a long and tortuous journey. A third alternative was to stay put and await developments. Given that Sulla was a thoroughly proactive commander who had realized that he had his enemy in as advantageous a position as he was likely to get, developments were not long in coming.

The Battle of Chaeronea

5

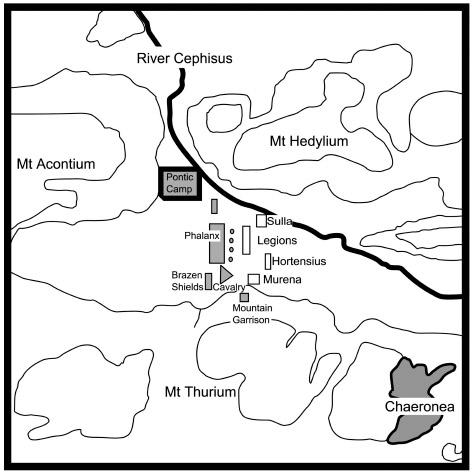

The troops whom Archelaus had sent to seize Chaeronea in the first place had retreated to a fortified position on Mount Thurium, above the town, while the main Pontic army had established itself in a pocket where the River Cephisus bent northward past Mount Hedylium and Mount Acontium blocked the end of the valley. This meant that Archelaus’ forces were in a highly secure position, having Mount Thurium to their right, Acontium behind and the River Cephisus to the left with Hedylium beyond that.

6

However, as the modern military maxim explains, ‘make it too hard for them to get in, and you can’t get out’. The only escape for the Pontic forces lay to the left, where the River Cephisus flowed between the mountains. This was certainly too small for a large army to leave in a hurry, but then, given the numbers involved, a Pontic defeat was unthinkable.

Sulla was a general with a lot of practice at thinking the unthinkable, and fighting the cavalry armies of Numidia had given him considerable experience about the options available to an infantry army faced with a mobile enemy. Regarding the Pontic infantry, he, like other contemporary commanders, knew what any traveller on the London Underground can confirm: push a large body of men closely enough together and they cannot even scratch their noses, let alone defend themselves. The Pontic cavalry could be countered given the right terrain (as Archelaus had just done for Sulla) and the large number of enemy infantry could work against itself.

Whilst Sulla was girding himself for battle, Archelaus was not yet certain that Sulla was serious about fighting. The opening engagement of the battle appeared more like the sort of skirmish which had been part of the background noise over the previous fortnight. What Archelaus probably had not yet realized was to be the Second Battle of Chaeronea (Spring, 86 BC), kicked off with fighting around Mount Thurium. A group of native Chaeroneans had approached Sulla, offering to use their local knowledge of the terrain around the mountain to outmanoeuvre the Pontic force ensconced there. The idea was to get above the Pontics and throw and roll rocks down on them until they abandoned their position.

Reconstruction of the opening phase of the Battle of Chaeronea based largely on the description by Plutarch

Sulla agreed to the proposal and drew up his forces for battle in such a way that the Pontics, as they left the mountain, would receive a warm welcome from his lieutenant, Murena, who commanded the Roman left flank on the plain below. Murena had the support of whatever cavalry Sulla could give him, whilst Sulla took the rest to guard the right (river) flank. As the plain sloped slightly downhill towards the main Pontic army, Hortensius and his Macedonian veterans, in reserve to the rear, had a view of where they should prepare to deploy themselves.

The Chaeronean ambush was a disaster for the Pontic troops on the hill. They were driven off in confusion and lost some 3,000 men without striking a blow. Archelaus, hastily drawing up his men to meet the Roman challenge, was in time to see his force from the mountain run into Murena’s welcoming party, and from there break in confusion to run pell-mell for the shelter of their own ranks. This was frustrating because the Pontic scythed chariots were ready to go and the clear field they needed for their run-up was cluttered with fleeing friendlies. To make matters worse, the Romans were following-up fast; by the time Archelaus was able to unleash his chariots

they were unable to get up the momentum they needed. When they saw the chariots coming, the well-drilled Romans opened their ranks in the manner their forefathers had once practised with Hannibal’s elephants; rather than creating carnage in the Roman ranks, the chariots rushed madly through the Roman lines without actually hitting anyone. Once through, Mithridates’ men screeched to as much of a halt as the maddened horses could manage and attempted to wheel round and take the Romans in the rear. Sulla, however, had anticipated this and had laid on javelinmen to take down the chariots at their most vulnerable moment. Archelaus saw a bad day getting worse as his vaunted chariots vanished into the Roman ranks, their disappearance followed by howls of derision and the traditional chant of spectators at the Circus Maximus in Rome, demanding that the next set of riders come out to race.