Mission: Cook! (32 page)

Roberto Donna, both as friend and as inspiration, has no peer. The first time I met Roberto was at the Madison Hotel at a Beard Foundation dinner. Somehow, no food had been prepared to feed the chefs who had cooked the main dinner of the evening. Without missing a beat, Roberto appropriated half a dozen prehistoric-sized cuts of beef from the walk-in and cheerfully prepared salt-crusted prime rib with trimmings for us all. I would affectionately describe him as a happy warrior in the kitchen.

He now presides over the dining room at his restaurant, Galileo, in the nation's capital. Everything he does is filled with passion, as anyone who has ever worked in one of his kitchens will attest. His kitchen is not a quiet place, especially if his wishes are not immediately and flawlessly carried out. As magnificent as Galileo is, with its homemade cotechino sausages, agnolotti, mousses, and terrines; its universe of excellent pastas and sauces, cheeses, and risottos; and its vibrant and memorable soups and desserts, the real action, as in Rick's place in

Casablanca,

is in the back room. That is where, in his private dining workshop, his culinarian's lair,

Il Laboratorio,

he labors to find perfection. Here he creates ten- and twelve-course tasting menus for his clients in an intimate

venue, featuring not just fine Italian food but fine dining experiences to compete with any in the world. His flawless technique may be on full display in his Roasted Duck Liver with Cherry Sauce, but the effort and skill he puts into garnishing it with a single zucchini flower, which he stuffs and poaches whilst managing to keep every petal of the flower intact, is wondrous to behold. If passion is in the details, then my good friend is passion personified.

Decide what

you

are going to obsess over. Great cooking is seeing to the details.

STYLE AND SUBSTANCE

The importance of doing it with style and my road to the White House

Robert and Big George heating things up in the kitchen

I

N THE RUNNING GUN BATTLE BETWEEN STYLE AND SUBSTANCE, IT IS PROB

- ably true that style gets all of the good press whilst substance does all of the work. Style has all of the fun; substance does all of the planning and scheduling and even does the washing up afterward. Now, in any good fable, style usually gets its comeuppance, as in “The Tortoise and the Hare,” or “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” but in reality I think that the two are inextricably linked, like tea and crumpets, fish and chips, or love and marriage (at least in the best ones).

I had been invited to attend (as a guest) a gala luncheon charity event given by the Ladies Professional Golf Association, or the LPGA, which was being held at the Atlantic City Convention Center. I decided to walk over from the Taj Mahal to take a look. I was especially intrigued by the invitation because the cooking was going to be done by Charlie Trotter, out of Chicago.

Charlie Trotter is one of the best in the business. He is a consistent five-star Mobil chef, a multiple James Beard Award-winner, a chef who has had a real impact on the trade itself. He is a pioneer in the renaissance of the tasting menu, and

his exacting standards and the perfect judgment and balance in his dishes can make a single bite seem like an adventure. I had brought a friend of mine along, another chef, named Robert Caracciola, and we were looking forward to seeing and tasting what was on offer, and to a rare and well-earned day off. There's also no question that the “nosy” side of me wanted to poke around and see what was going on.

We arrived early, hoping to squeeze in a bit of reconnaissance, and there literally seemed to be

nothing

going on. I found one of the lovely ladies who was to be in charge of the event, and she looked much more worried than happy to see me. Apparently, due to a miscommunication of some kind, the stage for the presentation was practically bare, and nothing was ready for the impending arrival of the impresario, Mr. Trotter. No pots, no pans, no water, not a single chopped onion, not a towel or a spoon. Realization and panic were setting in for her at the same time. “I need your help,” she said. “What am I going to do?!”

There is nothing like rallying to the rescue of a damsel in distress to whet your appetite before a big dinner, and I'm generally happier in a setting where

I

can be the boss, for at least part of the evening anyway, so Bobby and I took off our jackets and set to work. We worked together at the Taj Mahal, and we ran across the boardwalk and raided the Taj's kitchens for carts full of everything we thought

we

would want at hand to put on a show. We arranged for Trotter's cooking gear, utensils, pots and pans, mise en place, even put nice clean liners in the garbage cans. Charlie arrived later than expected, due to a flight delay, and when he arrived was in no mood for hugs and kisses, so we backed off and stayed out of his way. He is very strict and nothing was really the way he had asked for it to be, but at least we had given him a fighting chance. We had stuck to rule number one: get the food on the plates. And it helps when the guy's a geniusâ¦his food was fantastic.

Having made a favorable impression, I was asked to put the LPGA event together on my own a couple of years hence, and I was in a mood to do it with some style. This was one of the events that started to build my reputation for putting on splashy parties. I brought in a number of chefs, including my old friends Ming Tsai and Marcus Samuelsson of Aquavit; about forty in all. My theme was “Chefs of the (Salad) Greens,” and I paired a fantastic chef with each of the golfers on the tour. The event was for the benefit of about twenty charities bundled together, so the facilities and the arena at the Taj Mahal had been donated, and therefore I actually had a respectable budget to work with, and I took advantage of it. The chefs took over management of their own stations, and were charged with producing the most incredible dishes they could devise. For the setting, I provided miniature “golf holes” with pin flags and

real grass

for each station. We laid fresh sod down over the entire ballroom floor.

I have a friend who lived near me at the time named Vivat Hong Pong, who is a wonderful guy and also happens to be the world's greatest ice sculptor. He is the Michelangelo of the chain saw, and he came and carved

golf carts

out of titanic blocks of ice that looked big and detailed enough to drive away in. The printers at the Taj had the bills of fare printed up to look like score cards. We raised lots of money, made a big splash in the South Jersey press, and had a heck of a lot of fun with it all. Sometimes you want a simple understated dinner for two, but at other times you have to pull out the big guns and throw a

party.

W

ITHOUT SUBSTANCE, THERE IS NO “THERE” THERE, AND THE CONVER

-sation never really gets started. That is why we slave over technique, search for the best combinations, write them into recipes, seek out only the finest, freshest ingredients, and refuse to compromise on quality. But all of this preparation seldom rises to the level of true greatness without style. Style adds a little flair, a little flourish, the tip of the hat, the gleam in the eye, the perfect remark to the perfect person at the perfect moment. It's the lady in the tramp, and the little bit of tramp in the lady. There is both high and low style, and every kind in between. The epitome of high style is probably Fred Astaire in anything, Cary Grant in

It Takes a Thief,

Princess Diana at the White House. An excellent example of low style is Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe's reply to a surrender demand from the German forces when surrounded in the Battle of the Bulge at Bastogne: “Nuts.” In both cases, you know it when you see it.

Whatever your personal “it” may be, you had might as well do it with style.

Sometimes style can mean just doing what comes naturally when the opportunity presents itself. When the time had come to leave the Taj Mahal, I remember interviewing for the executive chef position in Atlantic City at Caesar's and had just sat down to lunch with their top-tier executive team. They ordered a number of appetizers, among them a clam dish in a light savory sauce with garlic and herbs. I knew upon sampling the first bite that a mistake had been made. The clams had a weird metallic taste; the base of onions and garlic and herbs had been processed in a mechanical chopper of some kind and had imparted a metallic taste to the clams. I excused myself, made my way back into the kitchen, and quickly recooked the dish (with a few of my own touches), but this time I prepped the ingredients by hand. I brought the dish to the table and had my interviewers compare the results whilst I explained. They signed me up on the spot. A bit of knowledge and experience applied at the proper moment, with just a dash of style, clinched the deal.

SERVES

6

FOR THE RISOTTO

2½ cups lobster stock

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 tablespoon chopped shallots

1 cup Arborio rice

¼ cup white wine

2 ounces heavy cream

3

/

4

cup diced lobster meat, cooked

3 tablespoons freshly grated Parmesan cheese (plus a piece to shave for garnish)

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 tablespoon chopped fresh basil

Juice of 1 lemon

Salt and pepper

FOR THE CLAMS

24 littleneck clams, well scrubbed and rinsed

1 tablespoon minced garlic

1 tablespoon minced shallots

1 sprig of fresh thyme

¼ cup white wine

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 tablespoon chopped fresh parsley

6 sprigs of fresh basil

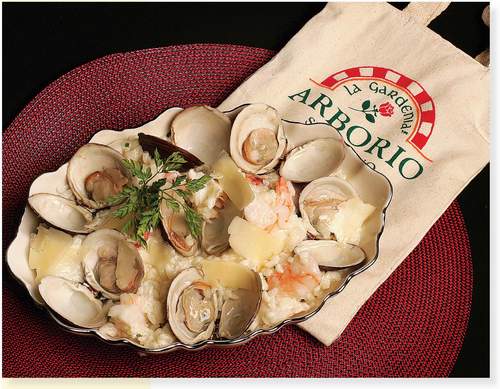

The preceding story put me in mind of one of my favorite clam dishes. Really the only secret to a delicious risotto is patience. Make the commitment to stir the Arborio rice constantly whilst it is cooking. Maybe try to remember the lyrics to “Stairway to Heaven” to pass the time when you are doing it; if you can manage to remember them all without cheating, the timing should be just about right.

Put

the lobster stock in a pot and

keep just below boiling.

(“Just below boiling” is the true definition of “simmering” in classical cooking.) On an adjacent burner, heat the olive oil in another large saucepan. Add the shallots to the oil and cook until soft. Stir the rice into the pan with the oil and shallots. Stir the rice until it becomes translucent, then pour the wine into the rice to deglaze the pan. When most of the liquid has evaporated from the rice pan, add one ladle of stock at a time to the risotto from the simmering pot of lobster stock on the next burner. The method is to let the risotto absorb the lobster stock gradually before you add the next ladleful to it. Once all the stock has been added and absorbed (after 15 to 25 minutes), add the heavy cream.

Remove the risotto from the heat. Stir in the lobster meat, cheese, butter, basil, and lemon juice. Season with salt and pepper to taste.

Place the clean clams in a saucepan; add the garlic, shallots, thyme, and white wine. Cover and bring to a simmer. Cook, covered, until the clams open. (Discard any clams that do not open). Swirl in the butter and parsley.

PRESENTATION

Mound the risotto in the center of each of 6 shallow bowls. Place 4 clams on top of each serving and drizzle the liquid from the clam pot. Garnish with a sprig of basil and shaved Parmesan.

A Note on Cooking with Wine

Cook with a wine you wouldn't mind drinking! You only need ½ cup for the Lobster Risotto with Clams, which means you can drink the rest with your meal. (Or while you're cookingâbut don't stop stirring that risotto!)

I

N GREAT COOKING, STYLE HAS A LOT TO DO WITH COMMUNICATION. STYLE

can run hot or cold. Some cooks like big, hearty preparations that will feed an army, and others only want you to have an impeccably crafted bite or two before they are ready to take you in another direction. Style is always a reflection of personality. In the old days, the kitchen was walled off from the dining room, except in rare cases, and seldom the twain did meet. But Escoffier was able to pay exquisite homage and an everlasting compliment to a great singing diva of his day, Nellie Melba, with his creation Péche Melba. They never really even had to meet. He said all he wanted to say with warmed peaches, silky ice cream, raspberries, and red currant jelly. He could have remained forever in the back of the house and she would have understood completely.

I like to communicate with food, in the way it is presented, and with special or unlikely ingredients. I will design an evening dress for a beautiful woman made entirely of fiberglass and fitted with shelves for an assortment of spectacular hors d'oeuvres, and have her circulate through the room before dinner service. I will plant fireworks in your food for presentation if I think you will be duly impressed and entertained. I will spend tens of thousands of dollars to build a replica of an Italian village in a hotel in Atlantic City to serve you a plate of spaghetti (and it will be very good spaghetti). I really want you to have a good time, in style.

It is epigrammatic in the business that “you eat with your eyes first.” It's true. The mix of colors on a plate, the arrangement of items, evocative compositionâall are important to the experience. There should always be a certain amount of “come hither” on the plate, an invitation to pleasure. I think that the presentation on the plate should delight the eye, like fine sculpture or painting, as well as reflect the sensibilities of the artist, that is to say, the chef.

These four words, which I drill into the heads of my chefs, are the essence of my style of presentation on the plate: