Miracles of Life (2 page)

Authors: J. G. Ballard

This rather impressed me, and I thought long and hard as

we sailed back across the river, the China Printing ferry

avoiding the dozens of corpses of Chinese whose impoverished

relatives were unable to afford a coffin and instead launched them onto the sewage streams from the Nantao

outfall. Decked with paper flowers, they drifted to and fro as

the busy river traffic of motorised sampans cut through their

bobbing regatta.

Shanghai was extravagant but cruel. Even before the

Japanese invasion in 1937 there were hundreds of thousands

of uprooted Chinese peasants drawn to the city. Few found

work, and none found charity. In this era before antibiotics,

there were waves of cholera, typhoid and smallpox epidemics,

but somehow we survived, partly because the ten

servants lived on the premises (in servants’ quarters twice

the size of my house in Shepperton). The huge consumption

of alcohol may have played a prophylactic role; in later years

my mother told me that several of my father’s English

employees drank quietly and steadily through the office day,

and then on into the evening. Even so, I caught amoebic

dysentery and spent long weeks in Shanghai General

Hospital.

On the whole, I was well protected, given the fears of kidnapping.

My father was involved in labour disputes with the

Communist trade union leaders, and my mother believed

that they had threatened to kill him. I assume that he

reached some kind of compromise with them, but he kept an

automatic pistol between his shirts in a bedroom cupboard,

which in due course I found. I often sat on my mother’s bed

with this small but loaded weapon, practising gunfighter

draws and pointing it at my reflection in the full-length mirror. I was lucky enough not to shoot myself, and sensible

enough not to boast to my friends at the Cathedral School.

Summers were spent in the northern beach resort of

Tsingtao, away from the ferocious heat and stench of Shanghai.

Husbands were left behind, and the young wives had a

great time with the Royal Navy officers on shore leave from

their ships. There is a photograph of a dozen dressed-up

wives each sitting in a wicker chair with a suntanned, handsomely

smiling officer behind her. Who were the hunters,

and who the trophies?

Amherst Avenue was a road of large Western-style houses

that ran for a mile or so beyond the perimeter of the International

Settlement. From the roof of our house we looked

across the open countryside, an endless terrain of paddy

fields, small villages, canals and cultivated land that ran in

the direction of what later became Lunghua internment

camp, some five miles to the south. The house was a three-

storey, half-timbered structure in the Surrey stockbroker

style. Each foreign nationality in Shanghai built its houses in

its own idiom – the French built Provençal villas and art

deco mansions, the Germans Bauhaus white boxes, the

English their half-timbered fantasies of golf-club elegance,

exercises in a partly bogus nostalgia that I recognised

decades later when I visited Beverly Hills. But all the houses,

like 31 Amherst Avenue, tended to have American interiors – overly spacious kitchens, room-sized pantries with giant

refrigerators, central heating and double glazing, and a bathroom

for every bedroom. This meant a complete physical

privacy. I never saw my parents naked or in bed together, and

always used the bath and lavatory next to my own bedroom.

By contrast, my own children shared almost every intimacy

with my wife and me, the same taps, soap and towels, and I

hope the same frankness about the body and its all too

human functions.

But physical privacy may have been more difficult for my

parents to achieve in our Shanghai home than I could have

imagined as a boy. There were ten Chinese servants – No. 1

Boy (in his thirties and the only fluent English speaker), his

assistant No. 2 Boy, No. 1 Coolie, for the heavy housework,

his assistant No. 2 Coolie, a cook, two amahs (hard-fisted

women with tiny bound feet, who never smiled or showed

the least signs of affability), a gardener, a chauffeur and a

nightwatchman who patrolled the drive and garden while we

slept. Lastly there was a European nanny, generally a White

Russian young woman who lived in the main house with us.

The cook’s son was a boy of my age, whose name my

mother remembered until her nineties. I tried desperately to

make friends with him, but never succeeded. He was not

allowed into the main garden, and refused to follow me

when I invited him to climb the trees with me. He spent his

time in the alley between the main house and the servants’

quarters and his only toy was an empty Klim tin that had once held powdered milk. There were three holes in its lid,

through which he would drop small stones, then remove the

lid and peer inside. He would do this for hours, mystifying

me completely and challenging my infinitely short attention

span. Aware that I had a bedroom filled with expensive

British and German toys (ordered every September from

Hamleys in London), I made a selection of cars, aeroplanes,

lead soldiers and model battleships and carried them down

to him. He seemed bemused by these strange objects, so I left

him to explore them. Two hours later I crept back and found

him surrounded by the untouched toys, dropping stones

into his tin. I realise now that this was probably a gambling

game. The toys had been a genuine gift, but when I went to

bed that night I found that they had all been returned. I hope

that this shy and likeable Chinese boy survived the war, and

often think of him with his tin and little pebbles, far away in

a universe of his own.

This large number of servants, entirely typical among the

better-off Western families, was made possible by the

extremely low wages paid. No. 1 Boy received about £30 a

year (perhaps £1000 at today’s values) and the coolies and

amahs about £10 a year. They lived rent-free but had to buy

their own food. Periodically a delegation led by No. 1 Boy

would approach my mother and father as they sipped their

whisky sodas on the veranda and explain that the price of

rice had risen again, and presumably my father increased

their pay accordingly. Even after the Japanese seizure of the International Settlement in December 1941 my father

employed the full complement of servants, though business

activity had fallen sharply. After the war he explained to me

that the servants had nowhere to go and would probably

have perished if he had dismissed them.

Curiously, this human concern ran hand in hand with

social conventions that seem unthinkable today. We

addressed the servants as ‘No. 1 Boy’ or ‘No. 2 Coolie’ and

never by their real names. My mother might say, ‘Boy, tell

No. 2 Coolie to sweep the drive…’ or ‘No. 2 Boy, switch on

the hall lights…’ I did the same from a very early age. No. 1

Boy, answering my father, would say ‘Master, I tell No. 2 Boy

buy fillet steak from compradore’ – the lavishly stocked

food emporium in the Avenue Joffre which supplied our

kitchen.

Given the harsh facts of existence on the streets of

Shanghai, and the famine, floods and endless civil war that

had ravaged their villages, the servants may have been

reasonably content, aware that thousands of destitute

Chinese roamed the streets of Shanghai, ready to do

anything to find work. Every morning when I was driven to

school I would notice fresh coffins left by the roadside,

sometimes miniature coffins decked with paper flowers

containing children of my own age. Bodies lay in the streets

of downtown Shanghai, wept over by Chinese peasant

women, ignored in the rush of passers-by. Once, when my

father took me to his office in the Szechuan Road, near the Bund, a Chinese family had spent the night huddling against

the steel grille at the top of the entrance steps. They had been

driven away by the security guards, leaving a dead baby

against the grille, its life ended by disease or the fierce cold.

In the Bubbling Well Road our car had to halt when the

rickshaw coolie in front of us suddenly stopped, lowered his

cotton trousers and leant forward over his shafts, defecating

a torrent of yellow liquid at the roadside, to be stepped in by

the passing crowds and carried all over Shanghai, bearing

dysentery or cholera into every factory, shop and office.

As a small boy aged 5 or 6 I must have accepted all this

without a thought, along with the backbreaking labour of

the coolies unloading the ships along the Bund, middle-aged

men with bursting calf veins, swaying and sighing under

enormous loads slung from their shoulder-yokes, moving a

slow step at a time towards the nearby godowns, the large

warehouses of the Chinese merchants. Afterwards they

would squat with a bowl of rice and a cabbage leaf that

somehow gave them the energy to bear these monstrous

loads. In the Nanking Road the Chinese begging boys ran

after our car and tapped the windows, crying ‘No mama, no

papa, no whisky soda…’ Had they picked up the cry thrown

back at them ironically by Europeans who didn’t care?

When I was 6, before the Japanese invasion in 1937, an old

beggar sat down with his back to the wall at the foot of our

drive, at the point where our car paused before turning into

Amherst Avenue. I looked at him from the rear seat of our Buick, a thin, ancient man dressed in rags, undernourished

all his life and now taking his last breaths. He rattled a

Craven A tin at passers-by, but no one gave him anything.

After a few days he was visibly weaker, and I asked my

mother if No. 2 Coolie would take the old man a little food.

Tired of my pestering, she eventually gave in, and said that

Coolie would take the old man a bowl of soup. The next day

it snowed, and the old man was covered with a white quilt. I

remember telling myself that he would feel warmer under

this soft eiderdown. He stayed there, under his quilt, for

several days, and then he was gone.

Forty years later I asked my mother why we had not fed

this old man at the bottom of our drive, and she replied: ‘If

we had fed him, within two hours there would have been

fifty beggars there.’ In her way, she was right. Enterprising

Europeans had brought immense prosperity to Shanghai,

but even Shanghai’s wealth could never feed the millions of

destitute Chinese driven towards the city by war and famine.

I still think of that old man, of a human being reduced to

such a desperate end a few yards from where I slept in a

warm bedroom surrounded by my expensive German toys.

But as a boy I was easily satisfied by a small act of kindness,

a notional bowl of soup that I probably knew at the time was

no more than a phrase on my mother’s lips. By the time I was

14 I had become as fatalistic about death, poverty and hunger

as the Chinese. I knew that kindness alone would feed

few mouths and save no lives.

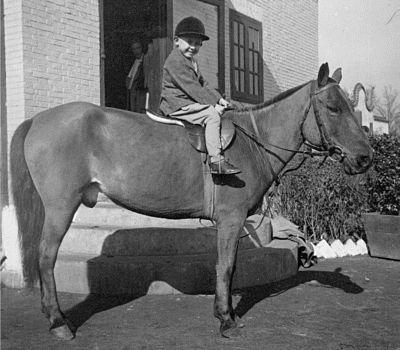

Myself aged 5 at my riding school in Shanghai

.

I remember very little before the age of 5 or 6, when I joined

the junior form of the Cathedral School for boys. The school

was run on English lines with a syllabus aimed at the School

Certificate examinations or their pre-war equivalent, heavily

dominated by Latin and scripture classes. The masters were

English, and we were made to work surprisingly hard, given

the nightclub and dinner-party ethos that ruled the parents’

lives. There were two hours of Latin every other day and a

great deal of homework. The headmaster was a Church of

England clergyman called the Reverend Matthews, a sadist who was free not only with his cane but with his fists,

brutally slapping quite small boys. I’m certain that today

he would be prosecuted for child abuse and assault.

Miraculously I escaped his wrath, though I soon guessed

why. My father was the chairman of a prominent English

company, and later vice-chairman of the British Residents

Association. I noticed that the Reverend Matthews only

caned and slapped the boys from more modest backgrounds.

One or two were beaten and humiliated almost

daily, and I’m still surprised that the parents never complained.

Bizarrely, this was all part of the British stiff-upper-lip

tradition, no match as it would turn out for another

violent tradition, bushido, and the ferocious violence meted

out by Japanese NCOs to the soldiers under their command.

When the Reverend Matthews was interned he underwent

a remarkable sea change: he abandoned his clerical collar

and spent hours sunbathing in a deckchair, and even became

something of a ladies’ man, as if at last able to throw off the

disguise imposed on him by a certain kind of English self-

delusion.

Outside school I remember a great many children’s parties,

every child escorted by its refugee nanny, a chance for

White Russian and German Jewish girls to exchange gossip.

During school holidays we would drive every morning to the

Country Club, where I spent hours in the swimming pool

with my friends. I was a strong swimmer, and won a small

silver spoon for coming first in a diving competition, though I wonder if the prize was awarded to me or to my parents.