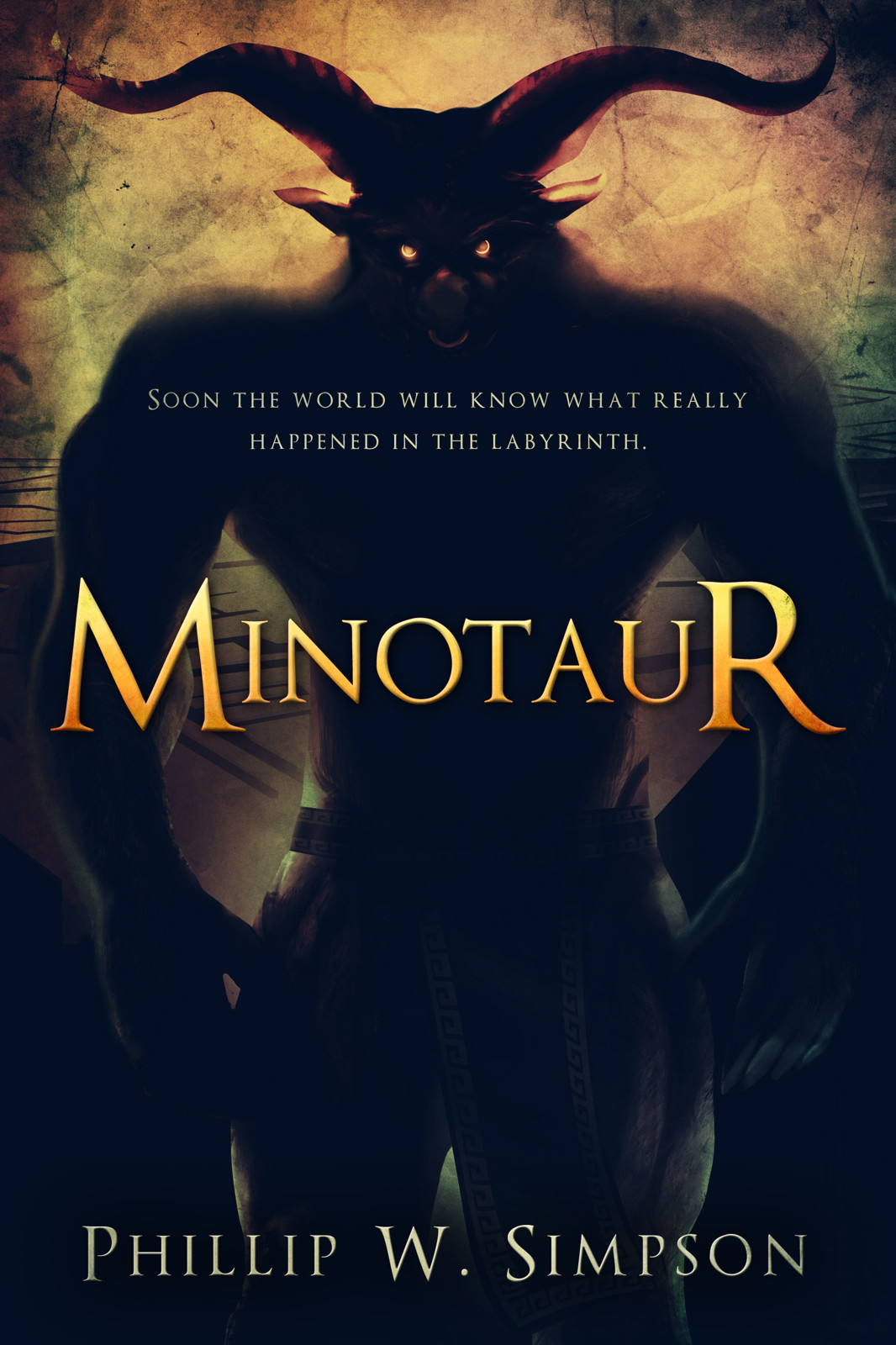

Minotaur

Authors: Phillip W. Simpson

Tags: #YA, #fantasy, #alternate history, #educational, #alternate biography, #mythical creatures, #myths, #legends, #greek and roman mythology, #Ovid, #minotaur

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The author makes no claims to, but instead acknowledges the trademarked status and trademark owners of the word marks mentioned in this work of fiction.

Copyright © 2015

MINOTAUR by PHILLIP W. SIMPSON

All rights reserved. Published in the United States of America by Month9Books, LLC.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Published by Month9Books

Cover designed by Najla Qamber Designs

Cover Copyright © 2015 Month9Books

Map of ancient Greece used with permission from

greeka.com

.

For Emeritus Professor Vivienne Gray. Emeritus Professor Geoffrey Irwin and Professor Tanya Fitzgerald. Thanks for instilling within me a sense of wonder and thirst for knowledge about the ancient world.

“With record of his deeds. When men shall have read of

…

the mingled form of bull and man.”

Ovid, Heroides 2. 67 ff

“Krete rising out of the waves; Pasiphae, cruelly fated to lust after a bull, and privily covered; the hybrid fruit of that monstrous union - the Minotaurus, a memento of her unnatural love.”

Virgil, Aeneid 6. 24

“What Cretan bull [the Minotauros], fierce, two-formed monster, filling the labyrinth of Daedalus with his huge bellowings, has torn thee asunder with his horns?”

Seneca, Phaedra 1170

“Theseus escaped the cruel bellowing and the wild son of Pasiphae, the Minotauros and the coiled habitation of the crooked labyrinth.”

Callimachus, Hymn 4 to Delos 311

Cretan Royal family

King Minos:

King of Crete. Stepfather of Minotaur.

Queen Pasiphae:

Queen of Crete. Mother of Minotaur.

Princess Ariadne:

daughter of King Minos and Queen Pasiphae of Crete.

Prince Asterion:

Also known as the Minotaur or just Minotaur. Sometimes as the ‘starry one.’ Son of Queen Pasiphae of Crete and the Greek god of the sea, Poseidon. Step-son of King Minos of Crete.

Prince Glaucus:

Son of King Minos and Queen Pasiphae of Crete. Youngest sibling to Asterion.

Prince Androgeus:

eldest son of Minos and Pasiphae. Brother of Asterion.

Prince Catreus:

Son of King Minos and Queen Pasiphae of Crete. Twin brother of Deucalion. Younger brother of Asterion.

Prince Deucalion:

Son of King Minos and Queen Pasiphae of Crete. Twin brother of Catreus. Younger brother of Asterion.

Princess Phaedra:

Illegitimate daughter of King Minos.

Cretan retainers

Daedalus:

Master craftsman. Builder of the labyrinth with his son, Icarus.

Icarus:

Master craftsman. Builder of the labyrinth with his father, Daedalus

Alcippe:

Nursemaid for the King’s children on Crete.

Paris:

Martial trainer in the palace of King Minos of Crete.

Athenians

Prince Theseus:

Prince of Athens. Son of King Aegeus and Poseidon.

Princess Aethra:

Mother of Theseus

King Aegeus:

King of Athens. Father of Theseus.

Queen Medea:

Queen of Athens

Other

Publius Ovidius Naso:

Also known as Ovid. Roman poet in 1st century BC.

Periphetes:

An outlaw

Procrustes:

An outlaw

Sciron:

An outlaw

Sinis:

An outlaw

The ship swept into port at Iraklion. Swaying slightly, Ovid stood at the rail and waited impatiently for it to dock, eager to see the sights and sounds of this island. Shipboard life, whilst vaguely entertaining, had begun to be a little monotonous.

Crete was a place he’d always been keen to visit, especially given his current work in progress. His most ambitious work to date. The

Metamorphoses

, his epic poem of Greek and Roman mythology, was almost complete. He considered it his

magnum opus

, his greatest work—something that he was immensely proud of. It would, he hoped, cement his place amongst the best Roman poets and live on long after his death. It was a monumental piece of work, comprising fifteen books and over two hundred and fifty Greek and Roman myths, painstakingly researched, rewritten and reinterpreted. It chronicled the history of the world from its creation all the way through to the reign of Julius Caesar. All that remained was a little editing and some fact checking and then it would be ready—he hoped. Ovid desperately needed it to be a success. Even poets with the Emperor’s favor could not afford to waste years on an unpopular work.

After working for so long, he’d had a sudden desire to get out, to actually see some of the places he’d been writing about. To see where these events had taken place. Not that it was especially important—most of his work had taken a decidedly creative approach to historical events—but it was invigorating nonetheless. He was a poet after all, not an historian. That was why he was on Crete. To see for himself the fabled home of the Minotaur.

Ovid’s thoughts turned for a moment to Rome. For once, he didn’t miss the bustling metropolis. He wondered for a moment what his daughter was doing. No doubt busy with his three grandchildren. They would have liked this trip, but he had quickly discarded the idea of bringing them along as foolhardy. At fifty, he felt old. The grandchildren exhausted him.

He disembarked, unburdened by any baggage other than a wineskin. A sailor trailed in his wake, carrying bags that contained his few important items; his writing implements and a few changes of clothes.

The port was a bustling hive of activity; sailors and dock workers vying with each other for elbow room, loading and unloading crates, urns, and a bewildering array of other products, which included live animals and people like himself.

A nearby voice raised in anger drew his attention amongst the chaos. A circle of bodies formed, incorporating Ovid into their midst. Within the circle, two figures stood. A shattered urn lay at their feet, shards of broken pottery lying in pools of what was clearly wine. Ovid drew a long breath in, savoring the delicious fumes even as he mourned the waste of good wine slowly evaporating.

One was an average sized man, unshaven with hair that looked like it had been chopped and sawn off with a clumsy blade. He wore a battered and torn tunic that appeared Roman in origin. Facing him was perhaps the largest man Ovid had ever seen. He stood head and shoulders above the other man and most of the others that gathered eagerly nearby. The simple tunic he wore could hardly contain his chest and arms, thick with corded muscle. Legs like seasoned oaks supported him.

The huge man’s tunic marked him as Cretan. Ovid really didn’t think Cretans were so, well, large.

“You clumsy fool,” snarled the smaller man. “You’ll pay for that.”

“I’m sorry,” said the huge man. “It was an accident.” A breeze suddenly sprung up, wafting the man’s long, greasy hair so that his face was suddenly revealed. His cheek bore evidence of ancient scars.

“Pay me now,” said the other man, holding out his hand expectantly.

The giant shook his head. “I have no money to pay,” he said, almost sadly.

The smaller man’s face twisted in anger. “Then my fist will extract payment,” he said, aiming a mighty blow at his opponent.

The huge man did nothing other than bring his hand up. He caught the fist of his attacker, stopping it dead like it had impacted with a stone wall.

The other man’s eyes went wide with surprise. He tried to wrestle his hand back from his opponent but found that it was stuck fast. The situation might’ve degenerated into something much worse then but for the intervention of the town’s garrison.

Three legionaries were pushing their way through the crowd.

“Break it up,” shouted one of them. The crowd grudgingly dispersed, grumbling. The two antagonists melted away with them.

The legionaries pushed through them until they were standing before Ovid.

“Publius Ovidius Naso?” said one of them.

Ovid sighed wearily. He was beginning to sober up, which didn’t exactly improve his mood. “That is my name, yes, but most call me Ovid.”

If the legionnaire was annoyed or disconcerted, he didn’t show it. “The Emperor sent word you would be coming. You are here to see the palace at Knossos?”

“I am indeed,” said Ovid.

The legionnaire nodded. “Please come with us, sir.”