Millions Like Us (43 page)

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

SOE agents

in the field, preparing to assist operations behind enemy lines in France, were supported by the FANYs, who were kept busy sewing French tailors’ labels into the clothes that would help to disguise them. It was also the job of the FANYs to offer agents the lethal ‘L’ tablet, to be taken if they were captured.

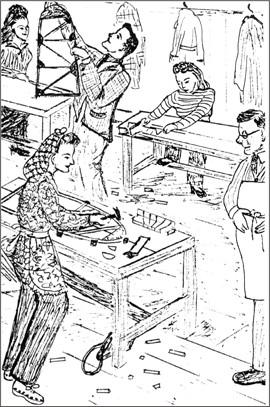

Making gliders in the Wolverton workshop: the tools and construction process are evidence of Doris’s memory for detail. But notice also her handbag under the workbench, her hairnet and her heavily nailed clogs.

Senior Wren Christian Lamb

(née Oldham) had been assigned to a post in Whitehall under Admiral Mountbatten. Here she observed the comings and goings of Winston Churchill and a number of scientific boffins. There was a ‘sense of urgency in the atmosphere, humming with activity’, but it was not till years later that Christian understood that these offices in Whitehall were the very heart of Operation Overlord. It was here that the prefabricated floating ‘Mulberry’ harbours were devised; here that the PLUTO pipeline – to run from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg – was conceived, along with the entire programme for the construction and concealment of the caissons, breakwaters, pontoons and floating ramps which would make the invasion feasible. Christian herself was sworn to the utmost secrecy about her job. She was among the few who knew that the landings would be on the Normandy coast. Working from large-scale maps of France pinned up on her office wall, it was her task to

identify everything visible that could be seen from the bridge of an approaching invasion craft.

WAAF Edna Hodgson

meanwhile had been allocated to the typing pool of General Eisenhower’s HQ in Bushey Park. Edna had no knowledge of the invasion date. But, as the time got closer, her working hours were prolonged. She often arrived at 8.30 a.m. and worked through till the early hours of the next morning on lunch and a snack, surviving on three or four hours’ sleep a night.

Some of the Wrens based in the south of England ports –

like Maureen Bolster

on HMS

Tormentor

in Southampton – were in on the most closely guarded secret in Britain’s history. Maureen was a faithful correspondent to her beloved fiancé, Eric Wells, who was based in North Africa, but as the time got closer she could do no more than hint to him of her real forebodings:

1 May 1944

My dearest

The first of May – the first of May already. It can’t be long now. I find it hard to take it in that England, my country, is on the verge of her greatest campaign of all time. It’s too immense, too shattering.

I hardly dare think what it will mean, the lives that will be lost, the numbers of everything involved – ships, planes, armour, men. One waits impatiently, wanting to get the strain of waiting over yet dreading it …

Everyone is expectant, unsettled …

On his last leave

before the invasion Eddie Parry returned to Moreton and looked up Helen Forrester before rejoining his Commando force. He would be in the forefront of the landings, and Helen tried not to think too hard about his prospects. Returning, Eddie missed the train. The May night was warm, and they walked to the Wirral bus stop together. At the foot of Bidston Hill he stopped, and there, under the starlit sky, asked Helen to marry him: ‘after the war – when I’ve got started again’. It was the last thing she was expecting. Eddie, the foul-mouthed rascal, the tough adventurer; surely holy matrimony was the last thing on his mind? He folded her in his arms. ‘I want to come back to you, Helen. Nobody else.’ Her self-control crumbled. What did she want? A husband, yes. She knew that Eddie was not the conscientious, devoted type. But more than that, she realised she wanted

him

: ‘desire shot through me’. Perhaps she was

being too demanding. Perhaps it would be all right. He would be reckless, forgetful, he would not live up to her dreams – but he would not desert her. ‘ “Yes,” I said, and put my arms round his neck.’ He kissed her solemnly and with passion. The night became cold. Eddie told Helen to go home, kissed her one more time and, without turning round, headed off to catch his bus.

Through May the sense of expectation intensified.

Sylvia Kay,

who worked General Eisenhower’s private switchboard (known as the ‘Red Board’), was told that she must prepare to move to an unknown destination. Next morning she and her colleagues were trucked to Cosham near Portsmouth. They were given tented accommodation and detailed to run the switchboard operation under canvas from a base in Cosham Forest; ‘it was a sea of mud’. Just north of Portsmouth, at the operation’s nerve centre of Fort Southwick,

ATS volunteer Mary Macleod

spent long days working in an underground cavern, typing out meticulous invasion plans, much of them in code. Meanwhile hundreds of firewomen joined their male counterparts to guard ammunition dumps.

Across the south of England, hospitals had been cleared of civilian patients prior to the invasion. Rows of beds now stood ominously empty.

A young Irish nurse,

Nancy O’Sullivan, based at a 1,000-bed hospital in Surrey, had been waiting for weeks. She and her colleagues scrubbed the wards and scrubbed them again.

QA Maureen Gara

was sent to East Anglia to prepare for D-day. There, she and her colleagues spent their spare time stitching together a huge red cross out of hessian, to serve as a ground marker for air crew, hostile or otherwise.

Meanwhile, Monica

Littleboy and her fellow ambulance-driving FANYs were posted to the Isle of Wight, where they prepared to be on the receiving end of many thousands of returning casualties.

On 24 May Elsie Whiteman

came home from working in her components factory in Croydon and wrote up her diary: ‘More hordes of bombers over this morning. The invasion seems very imminent and we hardly expect to get our Whitsun holiday.’ But still nothing was announced. ‘Friday 26th May. Everyone anxiously expecting the Second Front every day, but the weekend passed quietly.’ The assault troops were given embarkation leave.

Twenty-eight-year-old Aileen Hawkins

from Dorchester was an

ATS sergeant who as a girl had met the ageing Thomas Hardy in his home city. The courteous old poet had approved of her youthful verses; encouraged, she continued to write and publish poetry for the rest of her life. During the war Aileen married Bill, her pre-war sweetheart, now a Commando. As the day of the invasion approached she took time away from her anti-aircraft battery to say goodbye to him, knowing that these might be their last hours together:

End of D-Day Leave

Please, hold back the dawn, dear God

I cannot bear to let him go,

the world’s a battle field out there

big distant guns pepper the skies

a wailing siren stabs the air.

This moon-washed room our paradise

where we have had such little time

to share this precious love of ours.

My gentle one – a soldier now –

these years have left their mark on him,

touching his war-wearied face

I almost stare into his dreams …

…

The clock’s long hand will point the hour

the train will rattle from my view

and I will be alone once more

just longing for his love again.

‘God’, as he sleeps close to my heart,

slowly the end of leave draws near.

I cannot bear the time to part:

‘Hold back the dawn another hour’.

*

From 1 June all the Wrens had their shore leave cancelled. Phone calls were forbidden, and they were confined to barracks. ‘

We are gated,’

wrote Maureen Bolster to Eric. She and her friend Rozelle Raynes were kept busy delivering extra ammunition and signals to

the ships lying in wait. On 3 June, Maureen passed the soccer field and saw a mass of lads from the Commandos with their kit and tin hats resting in the sun. She was choked at the sight: ‘They looked so young I could hardly bear it and tears ran down my cheeks.’

D-day had been scheduled

for Monday 5 June. But on the 3rd Eisenhower and his generals reluctantly accepted that the weather forecasts they had been given made a provisional postponement necessary, and on Sunday the meteorological advisers were proved right as cloud and wind built up.

On the Isle of Wight

FANY Monica Littleboy and a friend bicycled out over the chalk downs to the west of the island and climbed up to Tennyson’s monument, from where they looked down at the Armada-in-waiting, lying at anchor on the Solent. ‘A glorious view from here all round, and here we proved that the shipping was even more intensified.’

Next morning, ‘dull and windy’, the FANYs were given a security lecture and warned that briefed personnel (‘BPs’) could be a risk if they were delirious while being carried as patients. ‘Anything we heard we were to forget.’

The typists working

in the Fort Southwick caverns had been instructed to type out two sets of documents, one of which would be signed by the chiefs. The first set gave orders to postpone the invasion, the other set commanded it to go ahead. On the evening of Sunday 4 June, in conference with his colleagues and advisers, Eisenhower heard that the weather was due to improve on Monday afternoon, sufficiently for the armada to sail overnight. The decision was made.

On 5 June village streets and country lanes in the south of England fell eerily silent. That day the news came through that Rome had fallen to the Allies.

Clara Milburn hung

up the Union Jack in the orchard and felt cheered; a letter had arrived from Alan that morning. This success meant that the war was a step closer to ending, and he was a step nearer home.

The Smell of Death

On the morning of 6 June 1944

Verily Anderson and Julie,

her Cockney mother’s help, were tidying up the Gloucestershire cottage when their children came rushing in from the garden:

‘Aeroplanes! Two tied together!’ James cried.

‘Huge,’ said Marian.

The sky was vibrating with sound. We ran out on to the lawn. None of us had seen aeroplanes since we came to the Cotswolds. Now they moved in a continuous stream over us.

‘They’re towing gliders,’ said Julie. ‘James is right.’

‘It’s our invasion!’ I said, jumping up and down. ‘It can’t be anything else. We’ve invaded France!’

There was no wireless in the cottage. They hurried across to their neighbour, the cowman’s wife, who was listening to the live broadcast:

‘Yes, It’s the invasion all right,’ she said. ‘They’ve landed in Portugal. Hundreds of our poor boys killed.’

‘Portugal?’ I repeated.

‘Some such name …’

‘Could it be Normandy?’ I suggested.

‘Yes, Normandy. Same thing no doubt. They’re all foreign places.’

All that day the planes streamed towards the coast, wing to wing, dropping an oily smoke screen as they went.

Sheets hung out

to dry that June morning were stained with black grease blown across by the gusty Channel breeze.

Sheila Hails, marooned

with her young baby in an isolated cottage near Lulworth on the Dorset coast, climbed the cliff that morning and saw an amazing sight:

I went up the grassy hill, and then I stood and blinked. There was an endless queue of ships sailing across the Channel. It was incredible, fantastic really, and I knew the invasion was happening.