Method and Madness: The Hidden Story of Israel's Assaults on Gaza

Read Method and Madness: The Hidden Story of Israel's Assaults on Gaza Online

Authors: Norman Finkelstein

Tags: #History, #Middle East, #Israel & Palestine, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Israel

© 2014 Norman G. Finkelstein

Published by OR Books, New York and London

Visit our website at

www.orbooks.com

First printing 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-939293-71-8 paperback

ISBN 978-1-939293-72-5 e-book

Cover design by Bathcat Ltd.

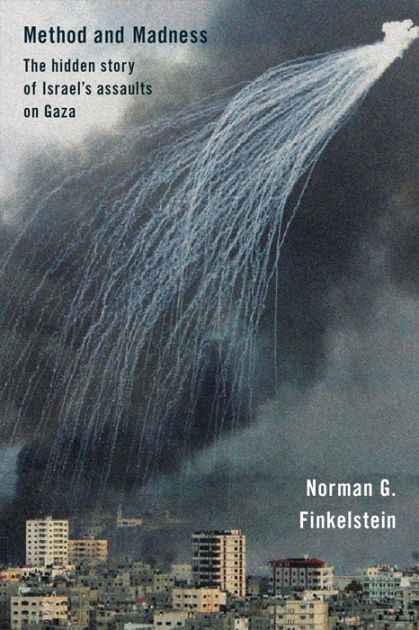

Cover photograph: Israel’s bombing of Gaza with white phosphorus during Operation Cast Lead, January 2009 (Human Rights Watch).

This book is set in Amalia. Typeset by CBIGS Group, Chennai, India.

Printed by BookMobile in the US and CPI Books Ltd in the UK.

To

Rudy, Carolyn, and Allan

This is a battle for hearts and minds. The IDF will make every effort to clearly demonstrate it can fight terrorism and win, thereby cementing itself in the enemy’s psyche as a beast one should not provoke

.

—Veteran Israeli journalist Ron Ben-Yishai on Operation Protective Edge

Israel has committed three massacres in Gaza during the past five years: Operation Cast Lead (2008–9), Operation Pillar of Defense (2012), and Operation Protective Edge (2014). It also killed in 2010 nine foreign nationals aboard a humanitarian vessel (the

Mavi Marmara

) en route to deliver basic goods to Gaza’s besieged population.

This book chronicles and analyzes these various Israeli assaults. It casts doubt on the accepted interpretation of their key triggers, features, and consequences. Each chapter reproduces (with minor stylistic changes) the author’s commentary as it was composed after each successive assault. The year in each chapter heading indicates when it was written.

A trio of themes form the connective tissue of the book’s narrative. First, Israel has repeatedly manufactured pretexts to achieve larger political objectives. Invariably, it resorted to military action against Hamas in order to provoke a violent response. Israel then exploited Hamas’s retaliation to launch a series of murderous assaults on Gaza.

Second, Israel has time and again eluded accountability for its war crimes and crimes against humanity. Both the Goldstone Report and Turkey’s attempt to prosecute Israel after the

Mavi Marmara

massacre proved stillborn. An International Criminal Court indictment of Israeli leaders after Operation Protective Edge also seems unlikely.

Third, at the end of each new round, the political balance between the antagonists did not change: each side declared victory, but neither side won. Such a stalemate has been much more tolerable for Israel than for the people of Gaza. The human and material losses suffered by Gazans have been of an incomparably greater magnitude. Moreover, Israel can live with the status quo, whereas Gaza, suffering under the double yoke of a foreign occupation and an illegal blockade, cannot. The fact that the indomitable will of the people of Gaza has repeatedly brought the Israeli killing machine to a standstill cannot but impress. However, such “negative” victories have yet to translate into a “positive” victory of a real improvement in Gaza’s daily life.

Palestinians are under neither legal nor moral obligation to desist from using armed force against Israel. Nonetheless, it is this author’s contention that nonviolent mass resistance, both in Gaza

and by its supporters abroad

, still offers the best prospect for ending the illegal siege and occupation. Armed resistance has been attempted many times and, notwithstanding its heroism and nobility, has failed to budge Israel a jot. The time is ripe to attempt militant nonviolent resistance, or so it is argued in the ensuing pages.

Norman G. Finkelstein

September 2014

I am grateful to Maren Hackmann-Mahajan and Jamie Stern-Weiner for both their editorial skills and the pleasures of collaborating with them. I am also indebted to the many individuals who forwarded me important information and read earlier drafts of this manuscript.

(2011)

“

IF ONLY IT WOULD JUST SINK INTO THE SEA

,” Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin despaired just before signing the 1993 Oslo Accord.

1

Although Israel had always coveted Gaza, its stubborn resistance eventually caused the occupier to sour on the Strip. In April 2004, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon announced that Israel would “disengage” from Gaza, and by September 2005 both Israeli troops and Jewish settlers had been pulled out. It would relieve international pressure on Israel and consequently “freez[e] . . . the political process,” a close advisor to Sharon explained, laying out the rationale behind the disengagement. “And when you freeze that process you prevent the establishment of a Palestinian state.” Harvard political economist Sara Roy observed that “with the disengagement from Gaza, the Sharon government was clearly seeking to preclude any return to political negotiations . . . while preserving and deepening its hold on Palestine.”

2

Israel subsequently declared that it was no longer the occupying power in Gaza. However, human rights organizations and international institutions rejected this contention because, in myriad ways, Israel still preserved near-total dominance of the Strip. “Whether the Israeli army is inside Gaza or redeployed around its periphery,” Human Rights Watch (HRW) concluded, “it remains in control.”

3

Indeed, Israel’s own leading authority on international law, Yoram Dinstein, aligned himself with the “prevalent opinion” that the Israeli occupation of Gaza was not over.

4

In January 2006, disgusted by years of official corruption and fruitless negotiations, Palestinians elected the Islamic movement Hamas into office. Israel immediately tightened its blockade of Gaza, and the US joined in. It was demanded of the newly elected government that it renounce violence, and recognize Israel as well as prior Israeli-Palestinian agreements. These preconditions for international engagement were unilateral, not reciprocal. Israel wasn’t required to renounce violence. It wasn’t compelled to withdraw from the occupied territories, enabling Palestinians to exercise

their

right to statehood. And, whereas Hamas was obliged to recognize prior agreements, such as the Oslo Accord, which undercut basic Palestinian rights,

5

Israel was free to eviscerate prior agreements, such as the 2003 “Road Map.”

6

In June 2007, Hamas consolidated its control over Gaza when it preempted a coup attempt orchestrated by Washington in league with Israel and elements of the Palestinian Authority (PA).

7

After Hamas checked this “democracy promotion” initiative of US President George W. Bush, Israel and Washington retaliated by tightening the screws on Gaza yet further. In June 2008, Hamas and Israel entered into a cease-fire brokered by Egypt, but in November of that year Israel violated the cease-fire by carrying out a bloody border raid on Gaza. Israel’s modus operandi recalled a February 1955 border raid during the buildup to the 1956 Sinai invasion.

8

The objective, then and now, was to instigate a backlash that Israel could exploit as a pretext for a full-blown assault.

On 27 December 2008, Israel launched Operation Cast Lead.

9

The first week consisted of air attacks, followed on 3 January 2009 by a combined air and ground assault. Piloting the most advanced combat aircraft in the world, the Israeli air corps flew nearly 3,000 sorties over Gaza and dropped 1,000 tons of explosives, while the Israeli army deployment comprised several brigades equipped with sophisticated intelligence-gathering systems and weaponry, such as robotic and TV-aided remote-controlled guns. During the attack, Palestinian armed groups fired some 925 mostly rudimentary “rockets” (and an additional number of mortar shells) into Israel. On 18 January, a cease-fire went into effect, but the economic strangulation of Gaza continued.

Israel officially justified Cast Lead on the grounds of self-defense against Hamas “rocket” attacks.

10

Such a rationale did not, however, withstand even superficial scrutiny. If Israel had wanted to avert the Hamas rocket attacks, it would not have triggered them by breaking the June 2008 cease-fire with Hamas. Israel also could have opted for renewing—and then honoring—the cease-fire. In fact, as a former Israeli intelligence officer told the Crisis Group, “the cease-fire options on the table after the war were in place there before it.”

11

More broadly, Israel could have reached a diplomatic settlement with the Palestinian leadership that resolved the conflict and terminated armed hostilities. Insofar as the declared objective of Cast Lead was to destroy the “infrastructure of terrorism,” Israel’s alibi of self-defense appeared even less credible after the invasion: overwhelmingly the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) targeted not Hamas strongholds but “decidedly ‘non-terrorist,’ non-Hamas” sites.

12

A close look at Israeli actions sustains the conclusion that the massive death and destruction visited on Gaza were not an accidental byproduct of the 2008–9 invasion but its barely concealed objective. To deflect culpability for this premeditated slaughter, Israel persistently alleged that Palestinian casualties resulted from Hamas’s use of civilians as “human shields.” Indeed, throughout its attack, Israel strove to manipulate perceptions by controlling press reports and otherwise tilting Western coverage in its favor. But the allegation that Hamas used civilians as human shields was not borne out by human rights investigations, while the gap between Israel’s claim that it did everything possible to avoid “collateral damage” and the hundreds of bodies of women and children dug out of the rubble was too vast to bridge.

“The attacks that caused the greatest number of fatalities and injuries,” Amnesty International found in its post-invasion inquiry,

were carried out with long-range high-precision munitions fired from combat aircraft, helicopters and drones, or from tanks stationed up to several kilometers away—often against preselected targets, a process that would normally require approval from up the chain of command. The victims of these attacks were not caught in the crossfire of battles between Palestinian militants and Israeli forces, nor were they shielding militants or other legitimate targets. Many were killed when their homes were bombed while they slept. Others were going about their daily activities in their homes, sitting in their yard, hanging the laundry on the roof when they were targeted in air strikes or tank shelling. Children were studying or playing in their bedrooms or on the roof, or outside their homes, when they were struck by missiles or tank shells.

13

It further found that Palestinian civilians, “including women and children, were shot at short range when posing no threat to the lives of the Israeli soldiers,” and that “there was no fighting going on in their vicinity when they were shot.”

14

An HRW study documented Israel’s killing of Palestinian civilians who “were trying to convey their noncombatant status by waving a white flag,” and where “all available evidence indicates that Israeli forces had control of the areas in question, no fighting was taking place there at the time, and Palestinian fighters were not hiding among the civilians who were shot.” In one instance, “two women and three children from the Abd Rabbo family were standing for a few minutes outside their home—at least three of them holding pieces of white cloth—when an Israeli soldier opened fire, killing two girls, aged two and seven, and wounding the grandmother and third girl.”

15

Unabashed and undeterred, Israel still sang paeans to the IDF’s unique respect for the “supreme value of human life.” Israeli philosopher Asa Kasher praised the “impeccable” values of the IDF, such as “protecting the human dignity of every human being, even the most vile terrorist” and the “uniquely Israeli value . . . of the sanctity of human life.”

16

The charges and countercharges over the use of human shields were symptomatic of Israel’s attempt to obfuscate what actually happened on the ground. In fact, Israel began its public relations preparations six months before Cast Lead, and a centralized body in the prime minister’s office, the National Information Directorate, was specifically tasked with coordinating Israeli

hasbara

(propaganda).

17

Nonetheless, after world opinion turned against Israel, influential military analyst Anthony Cordesman opined that, if it was now isolated, it was because Israel had not sufficiently invested in the “war of perceptions”: Israel “did little to explain the steps it was taking to minimize civilian casualties and collateral damage on the world stage”; it “certainly could—and should—have done far more to show its level of military restraint and make it credible.”

18

Israelis “are execrable at public relations,” Haaretz.com senior editor Bradley Burston weighed in, while according to respected Israeli political scientist Shlomo Avineri the world took a dim view of the Gaza invasion because of “the name given to the operation, which greatly affects the way in which it will be perceived.”

19

But if the micromanaged PR blitz ultimately did not convince, the problem was not that Israel failed to convey adequately its humanitarian mission or that the whole world misperceived what happened. Rather, it was that the scope of the massacre was so appalling that no amount of propaganda could disguise it.

What explains Israel’s brutal assault on a civilian population? Early speculation centered on the upcoming Israeli elections, scheduled to be held in February 2009. Jockeying for votes was no doubt a factor in this Sparta-like society consumed by “revenge and the thirst for blood.”

20

However, the principal motives for the Gaza invasion were to be found not in the election cycle but, first, in the need to restore Israel’s “deterrence capacity,” and, second, in the need to counter the threat posed by a new Palestinian “peace offensive.”

Israel’s “larger concern” in Operation Cast Lead,

New York Times

Middle East correspondent Ethan Bronner reported, quoting Israeli sources, was to “re-establish Israeli deterrence,” because “its enemies are less afraid of it than they once were, or should be.”

21

Preserving its “deterrence capacity” has always loomed large in Israeli strategic doctrine. In fact, it was a primary impetus behind Israel’s first strike against Egypt in June 1967 that resulted in Israel’s occupation of Gaza and the West Bank. To justify Cast Lead, Israeli historian Benny Morris wrote that “many Israelis feel that the walls . . . are closing in . . . much as they felt in early June 1967.”

22

Ordinary Israelis were no doubt filled with foreboding in June 1967, but Israel did not face an existential threat at the time (as Morris knows

23

) and Israeli leaders were not apprehensive about the war’s outcome. Multiple US intelligence agencies had concluded that the Egyptians did not intend to attack Israel and that, in the improbable case that they did, alone or in concert with other Arab countries, Israel would—in President Lyndon Johnson’s words—“whip the hell out of them.”

24

The head of the Mossad told senior American officials just before Israel attacked that “there were no differences between the US and the Israelis on the military intelligence picture or its interpretation.”

25

The predicament for Israel lay elsewhere. Spurred by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s “radical” nationalism, which climaxed in his defiant gestures in May 1967,

26

the Arab world had come to imagine that it could defy Israeli orders with impunity. Israel was losing its “deterrence capability,” Divisional Commander Ariel Sharon admonished Israeli cabinet members hesitant to launch a first strike, “our main weapon—

the fear of us

.”

27

In effect, “deterrence capacity” denoted, not warding off an imminent lethal blow, but instead keeping Arabs so intimidated that they could not even conceive challenging Israel’s freedom to carry on as it pleased, however ruthlessly and recklessly. Israel unleashed the war on 5 June 1967, according to Israeli strategic analyst Zeev Maoz, “to restore the credibility of Israeli deterrence.”

28

At the start of the new millennium, Israel confronted another challenge to its deterrence capacity. After a nearly two-decade-long guerrilla war, Hezbollah had ejected the Israeli occupying army from Lebanon in May 2000. The fact that Israel suffered a mortifying defeat, one celebrated throughout the Arab world, made another war well-nigh inevitable. Israel almost immediately began planning for the next round,

29

and in summer 2006 found a pretext when Hezbollah captured two Israeli soldiers inside Israel (several others were killed during the operation) and in exchange for their release demanded the freedom of Lebanese prisoners held by Israel. Although Israel unleashed the full fury of its air force and geared up for a ground invasion, it suffered yet another ignominious defeat. One indication of Israel’s reversal of fortune was that, unlike in any of its previous armed conflicts, in the final stages of the 2006 war it fought not in defiance of a UN cease-fire resolution but in the hope that a UN resolution would rescue it from an unwinnable situation. “Frustration with the conduct and outcome of the Second Lebanon War,” an influential Israeli think tank reported, prompted Israel to “initiate a thorough internal examination . . . on the order of 63 different commissions of inquiry.”

30