Mendel's Dwarf (6 page)

1

. Hamer et al.,

Science

, 1993.

F

rancis Galton, cousin of Charles Darwin, looked for evidence that intelligence runs in families—and found it, naturally enough, among his own august relatives. One wonders what he would have made of his exact contemporary, Gregor Mendel. One wonders what he would have made of the meanness of the world from which Mendel came, of the dull stupidity, of the grim labor in the fields, of the poverty and squalor. Mendel’s father was no more than a serf. He might have owned his small-holding, but he was still subject to the

Robot

. That was the world from which Mendel came.

Robot

is an emblematic word. Of course it was intended to be so from the moment that the playwright Karel Čapek took it from the lumber room of the Czech language and coined its modern sense.

1

In Mendel’s day,

Robot

was man, not machine: three days’ forced labor out of every week of a peasant’s life. Following the revolution of 1848, in which the peasants were emancipated, the

Robot

was abolished; but not before it had destroyed Anton Mendel. That was the family endowment that Gregor stood to inherit.

Galton, on the other hand, inherited a personal fortune and invented the science of eugenics in order to prove that the superior classes were, in fact, superior (in his particular case they were also sterile, but let that pass). In my thesaurus, “Galton’s law” comes immediately next to “Mendelian ratio.” There’s an irony.

The village is still there, of course, tucked away among the hills of northern Moravia—the very navel of Europe, as far from Madrid as from Moscow, as far from the Baltic as from the Mediterranean. It’s a pretty enough place. A rural idyll, you might think. The fields and woods lie quietly beneath the fragile summer sky now just as they did in Mendel’s day. The same stream still runs beside the same road (merely tarmacked now) down toward the Odra valley. The same trees—alder and willow and aspen—grow along the streambank, while across the fields to the north rise the foothills of the same mountains, still black with spruce. You can almost imagine the family still there in the cottage, Rosine stout and jolly, Anton sallow and saturnine, the two daughters, Veronika and Theresia, and the son Johann. You might imagine all that, but you would be far from the truth.

The fact is that although the geography may be the same and most of the buildings may be the same, the place itself has changed beyond reckoning. The name has changed, the language has changed, the people have changed, the whole world has changed. Nothing is the same. Heinzendorf is a vanished world—it is Hynčice now, a straggle of orchards and cottages and barns along a single street, merging into the neighboring village of Vražné that was once Grosspetersdorf. The mountains that rise to the north are part of the Sudety range.

This is the Sudetenland.

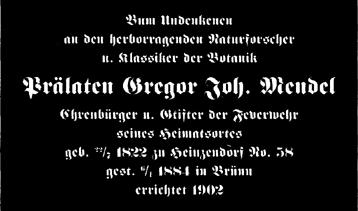

At the crossroads in the center of this idyllic village is a curious

building. It looks like a hybrid between a bus shelter and a chapel. Raised above the roof of the hut is a black stone plaque inscribed in gothic lettering:

It is not difficult to imagine a detachment of soldiers in

feldgrau

halting at that crossroads and looking up at that plaque. It would be a fine autumnal day of 1938. They would have a halftrack perhaps; maybe a motorcycle and sidecar. They would look up at the inscription with the satisfaction of the liberator, while villagers—women in floral aprons with flour on their arms, and men in overalls and muddied boots—would come out of the houses and barns to welcome them.

“Hier wurde Mendel geboren,”

the villagers would explain.

“Mendel? Ein Jude?”

“Nein, nein.”

Laughter.

“Prälat Mendel. Entdecker der Genetik.”

A grinning, embarrassed relative would be produced as evidence. Conscious of race and blood, of the purity of their genes and the inferior nature of the Slavs, the soldiers would be delighted to learn that they had fetched up in Mendel’s home village. It would appear to them an omen. There would be laughter. Perhaps there would even be a photograph taken with a sharp, neat, futuristic Leica to send back to the family in Rostock.

Oświecim/Auschwitz is a two-hour drive away, just over the Polish border.

The Mendel house itself still stands, a stout cottage set back from the road up an overgrown path, surrounded by cherry and apple trees. There is a metal sign painted in the crude lettering of the onetime People’s Republic—

Památka G. Mendela

, the G. Mendel Memorial—and you get the key from the woman who runs the village shop. She is Czech, of course. She understands little German.

There are just two rooms open to the public, both whitewashed, both tainted with damp. On the walls are the usual photographs—Gartner, Nägeli, Darwin, the Augustinian friars—and the usual facsimiles of Mendel’s papers. There are diagrams of some of the pea crossings and a quotation from T. H. Morgan, and a stylized and inaccurate model of part of a DNA molecule. There is little else. Only in the inner room is there something that Mendel himself might have recognized: a tiled stove standing in one corner as mute witness to the long, hard winters.

In the visitors’ book someone has put the epithet

SudetenDeutscher

beneath his name.

What was it like, that distant, Sudeten German life one hundred and fifty years ago? Frugal, fearful of God, attentive to duty, I suppose. The future would have been no more than a continuation of the past, not subject to change. You accepted your lot, and visited the family graves regularly just to see what acceptance meant. You prayed and you worked. You didn’t question.

Johann Mendel escaped through the only door that stood half-open—education. In 1834, encouraged by the local schoolmaster, he sat the entrance examination to the Imperial Royal Gymnasium at Troppau (Opava) and won a place.

Imagine his mother’s pride when she heard the news: picture her in the kitchen, wiping her ruddy hands on a cloth and turning to embrace her young son in a powerful, maternal clasp. She had plans, we imagine: her uncle had once been a teacher, and she had similar plans for her son. And picture old Anton, swallowing bitterness and envy while slapping his son on the shoulder. “In my day you didn’t get opportunities like this, my boy. In my day you had to work to better yourself …”

“But the lad

has

worked. He’s worked with his

brain

.” The reproach would have been there just below the surface, the hint that Johann was destined for better things, the suggestion that by using your brains you could escape the clutches of serfdom and the

Robot;

and the implication that by marrying Anton Mendel, Rosine Schwirtlich had somehow stepped down a rung.

Johann was admitted to the grammar school on half-commons—the equivalent, I suppose, of free dinners. He worked hard and did well at his studies—

prima classis cum eminentia—

but escape wasn’t that easy, for in the winter of 1838 his father was badly injured while logging in the forests above Ostrau—while working under the

Robot

. A trunk broke loose and rolled onto him, and they brought him home on a cart with his chest half crushed.

Heinzendorf must have been rife with speculation. What would Johann Mendel do? The father survived more or less, but manual work was beyond him. What was the son, the only son, going to do? Grim and implacable, the

Robot

stood waiting in the shadows to claim Johann Mendel for his own.

Can there be a gene for stubbornness? Johann was a stubborn man, sure enough. He was stubborn in his work with the garden pea (eight years, eight generations, more than thirty thousand plants); he was stubborn in his battle with the taxman when he was abbot of the monastery; and he was stubborn then, when he was a mere boy of sixteen and his father was a near

invalid and the farm was going to wrack and ruin. It isn’t hard to imagine the rural drama that reigned in that cottage in the village of Heinzendorf when he came home. It isn’t difficult to picture the internecine quarrel that threatened to split the family apart—the jealousies, the accusations, the false appeals to duty and the dishonest appeals to affection, the whole caustic solution of a family dispute.

“The boy must be allowed to continue his studies,” Rosine would insist.

And old Anton, sitting in a chair by the stove, would cough and hack and bring up mucus and blood like evidence. “I’ve worked myself to the bone for this place. And I get it thrown back at me without so much as a thank-you.”

“It’s not like that, Father,” the son would try to explain, with little success.

“Oh, it’s exactly like that. Farm work’s beneath you, that’s the trouble. You think it’s beneath you. You think that you can become grand just by reading a few books …” Old Anton, hacking and spitting and pointing his finger at his son, with the daughters hovering in the background, pleading for him to stop. “You’ll do yourself an injury, Father.”

“You keep out of it. This isn’t the business of women.”

But it was. It was precisely the business of the women, for it was the daughters who held the key—the elder Veronika with her shining new husband and the young Theresia, Uncle Harry’s grandmother, then a mere child of eleven. I imagine they plotted the whole thing together with their mother and presented it as a fait accompli to the father. Veronika’s husband, Alois Sturm, had some money put away. He could buy the farm and so keep it in the family. The sale would raise enough money for Anton and Rosine to retire—he wasn’t in any fit state to carry on, was he?—and there would be something left over to support Johann at the university. And Theresia—stout, sensible Theresia—would surrender her own share of the inheritance,

her dowry in fact, to help her beloved brother with his studies.

So he stayed at his studies, living from hand to mouth, doing some private teaching, scratching out a living, battling with poverty and guilt.