Men of Honour (11 page)

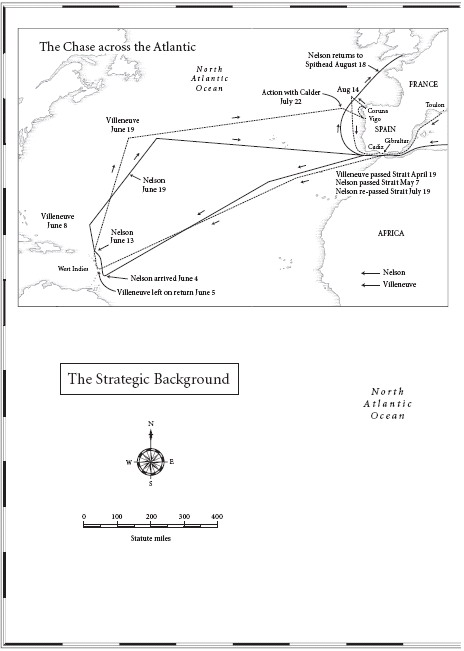

The French fleets failed to meet up in the Caribbean but Villeneuve, partly through some false information received by Nelson, kept one step ahead of him and on 5 June headed north and back for Europe. Nelson was exhausted, longing for home and England âto try and repair a very shattered Constitution.' âMy very shattered frame,' he wrote to his friend and agent Alexander Davison, âwill require rest, and that is all that I ask for.' Not yet though. He had to set out back across the Atlantic, in pursuit of the French: âBy carrying every Sail and using my utmost efforts I shall hope to close with them before they get to either Cadiz or Toulon to accomplish which most desirable object nothing shall be wanting on the part Sir of your most obedient servant. Nelson + Bronte'.

There is strain and exertion in every word. All he needed was proximity. Get close to them, and he felt he could rely on the destructive power of the fleet under his command. Every rag in every ship was hauled to the mast but he never caught them and never guessed at what the grand Napoleonic scheme might be. Villeneuve was heading, as his orders required, for Ferrol in northwest Spain, but Nelson was still thinking of the Mediterranean, and he headed for the Strait of Gibraltar. By 18 July, after a round trip of 6,686 miles, Cape Spartel, on the Moroccan side of the Strait, was sighted from the

Victory

, but no enemy in sight, ânor any information about them; how sorrowful this makes me, but I cannot help myself'. They had given him the slip.

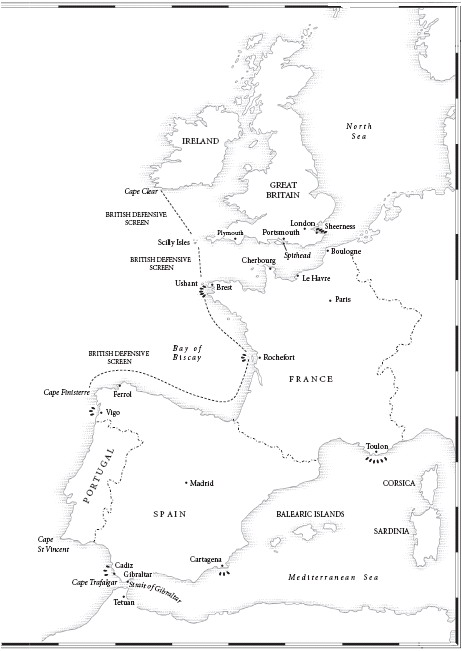

Any complacent sense of system that might have prevailed among the armchairs of London was totally absent from the fleet. Throughout the anxious summer, the feeling at sea was of a desperate stretched thinness to the British naval resource. Admiral Knight at Gibraltarâsomething of a complainerâfelt he had no ships with which to confront the Spanish in the Strait: âI therefore trust their Lordships will allow me to repeat to them the exposed situation of a British Admiral without the means of opposing this Host of armed Craft.' In Malta, the pivot of the British presence in the eastern Mediterranean, Sir Alexander Ball, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge acting as his secretary, wrote in full anxiety on 24 June 1805. âWe are in very great distress for Ships of war for the services of this island. Affairs here are drawing fast to a crisis.' His ships were dispersed in Constantinople, Trieste and off Sardinia. He of course had no idea where Nelson's fleet was, nor Villeneuve's; or even whether England might have been invaded.

On 19 July, after very nearly two years at sea, Nelson stepped ashore in Gibraltar. The next day he was writing to the Admiralty, assuring their Lordships âthat I am anxious to act as I think their Lordships would wish me, were I near enough to receive their orders. When I know something certain of the Enemys fleet I shall embrace their Lordships permission to return to England for a short time for the reestablishment of my health.'

If things had been different, the great events of 1805 might have reached their crisis at the end of July. Napoleon's army was waiting at Boulogne. It was the most effective invasion force ever assembled and would go on to win the most devastating victories against the Austrians and the Russians at Ulm and Austerlitz. The strategy of the French Mediterranean fleet had foxed Nelson. It is true that the British Channel Fleet still held the French shut into Brest. All that was needed was for Villeneuve to collect the

Spanish ships from Ferrol and the French squadron from Rochefort and to drive north to the Channel. The Brest fleet would emerge and in overwhelming numbers they would come to dominate the Channel as Napoleon had envisaged.

On 22 July, 100 miles west of Cape Finisterre, Villeneuve fell in with a British fleet under Sir Robert Calder and in fog and with a greasy swell sliding under them, met in an inconclusive battle for which Calder was pilloried in the British press. Nelson headed north from Gibraltar on 15 August. He left most of his ships with the Channel Fleet and in

Victory

went home to England, the arms of Emma Hamilton and rest. Any idea that the events of the preceding months had been governed by order and rationality would have summoned from him a hollow laugh. All was contingency, guesswork and desperation. He was reading in the newspapers, which he picked up from the Channel Fleet, of Calder's half-hearted engagement off Finisterre. As he wrote to his friend Thomas Fremantle:

Who can, my dear Fremantle, command all the success which our Country may wish? We have fought together and therefore know well what it is. I have had the best disposed Fleet of friends, but who can say what will be the event of a Battle? And it most sincerely grieves me, that in any of the papers it should be insinuated that Lord Nelson should have done better. I should have fought the Enemy, so did my friend Calder; but who can say that he will be more successful than another?

Napoleon wrote to Villeneuve, to tell him that âthe Destiny of France' lay in his hands. After the action with Calder's fleet, he went first into Vigo and then Coruña. He wrote to Decrès about the rotten condition of his fleet. The

Bucentaure

had been struck by lightning. His ships were floating hospitals. Masts, sails and rigging were

inadequate. His captains were brave but inefficient. His fleet was in disorder. On 11 August, full of apprehension, he left Coruña, but two days later, frightened by false intelligence of a British fleet to the north, he gave the order to turn south. On 22 August he entered Cadiz, where he had remained ever since, sunk in shame. On the same day, Napoleon had written him a letter from the camp at Boulogne, addressed to Villeneuve in Brest, where he was expected to arrive at any minute.

Vice-Admiral, Make a start. Lose not a moment and come into the Channel, bringing our united squadrons, and England is ours. We are all ready; everything is embarked. Be here but for twenty-four hours and all is ended.

Villeneuve failed the test of nerve which Napoleon had set him, but he failed it on rational grounds. His inadequate fleet would have been smashed by the sea-hardened ships of the British Channel Fleet and of Nelson's Mediterranean Fleet which were waiting for him off the Breton coast. Trafalgar would have occurred in August 1805, a thousand miles further north and the British would for ever after have celebrated the great victory of Ushant.

As it was, Villeneuve and his 33 ships were now shut into Cadiz by the small English squadron of between four and six ships-of-the-line under Collingwood, which had been cruising off the port since June. For months, they had been craning their ears to discover what was going on in Cadiz. And even now, reinforced on 30 August by Sir Robert Calder with 19 sail-of-the-line, there was no sense of the anxiety being over. Far from it. Fishing boats were stopped and boarded. Neutral American merchantmen were searched and their captains interrogated. Among the papers of Captain Bayntun of the

Leviathan

is the

Atlas Maritimo de España

, published in Madrid 1789, in its

handmade sailcoth cover, sewn by a sailor on the

Leviathan

, and many of the pages deeply water-stained. The chart of Cadiz Bay is covered in Bayntun's notes and lines, the anxious care of a blockading captain drawing in the bearings on the church at Chipion near St Lucar and the Cadiz lighthouse, working out the leading marks and the bearings on various fortifications around the city, carefully annotating and translating the table of soundings for the sand, gravel, rock and mud shoals south of the city. Even 200 years later, in a muniment room in England, it is a document drenched in anxiety.

All year long they had listened to the gossip coming out of Cadiz and all of it was transmitted back to London. The Spanish fleet was watering and taking on provisions. Admiral Gravina had been appointed to command. The Spanish crews had received five months' pay. It was now said that Villeneuve âwas likely to lose his head for his conduct, and it was supposed he would be sent a prisoner to Paris.' The Combined Fleet was reported bound to the Mediterranean. Couriers were seen leaving for Madrid and Paris at ten o'clock at night. Gravina was going to strike his flag, disgusted, the report said, with the conduct of the French.

In early September a spy somehow got to Collingwood a complete breakdown of the ships in Cadiz, including precise information on their captains and the number of guns per ship. On 19 September the entire Combined Fleet was said to be stored and complete with provisions, but in want of sailors. There followed âa general press on shore, and a strict search of French, and Spanish Deserters on board all the merchant Ships of every nation.' Battle would soon follow.

In the British fleet, this constant vigilance and anxiety exacted its price. A Lieutenant Wharton, in HMS

Bellerophon

on station off Ushant with the Channel Fleet under

Admiral Cornwallis, longs to go home. He has just heard that his father has died and his affairs are âin a very confused state'. He gives his request to his captain John Cooke, who sends it to the admiral, who sends it to the Admiralty. A minute in response, by Marsden, is written as usual on the corner of the letter: âThe expence of the Service does not permit Lt Whartons request to be complied with.' No relief; he must stick to the task.

On 18 August, Lieutenant Pasco, flag lieutenant on

Victory

, was suffering from rheumatism and âmy weak state of health'. Pasco wrote to Hardy, Hardy to Nelson, and Nelson to the Admiralty requesting that Pasco go ashore. The doctor on the flagship, William Beatty, recommended 14 days âCountry Air, Exercise and change of diet'. Captain Hardy himself had been âfor many months afflicted with very severe rheumatic complaints attended with maciation and privation of rest and obstinately resisting the efficacy of medicine', for which Beatty recommends

relaxation of some weeks, from the duties of Service, change of air, and Regimen, exercise on horseback, or in a carriage, together with the frequent use of the Tepid Bath.

Sir Richard Bickerton had âconfirmed affection of the liver'; Rear-Admiral Lord Northesk wants to go home âhaving urgent business in England'; Captain Morrison of the

Revenge

wants to go home: âA Rupture of some years Standing has lately become worse. I do not find my Health equal to the Duties of my profession.' Admiral Knight in Gibraltar had become too ill to do anything. On the

Achille

on 21 September, different officers were suffering from repeated liver pain and visceral obstruction, ulcered leg and consumption. Lieutenant Will Davies on

Spartiate

was suffering from ârapid Constitutional Decay, privation of appetite and general debility'.

By early October, John Wemyss, captain of the Royal Marines on board the

Bellerophon

wrote to his captain John Cooke:

Sir,

I beg leave to represent to you that Domestic Concerns of a most Urgent and particular Nature, render my immediate presence in England indispensably necessary to my private Interests, and induce me to request you would have the goodness to use your influence with the Commander in Chief, to permit me to proceed thither, either by appointing some Officer included in the late Promotion to serve on board the Bellerophon in my room, or granting me such leave of absence as his lordship may deem proper. From my situation on the List of Captains and having some time ago completed a Tour of Sea Duty, and not having during the last thirteen years troubled my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty for an indulgence, I trust will, in his Lordships Conscience, have due weightâ

I have the Honor to be

Your most Obedient and

Humble Servant

John Wemyss

Capt Royal Marines

A month and a half later, on 16 November, after Trafalgar had come and gone, when Cooke was dead and Wemyss recovering from a dreadful wound, Barham wrote baldly:

'Aqunt Lord Collingwood that Capt Wemyss's request cannot be complied with.'