Meg: Hell's Aquarium (49 page)

Read Meg: Hell's Aquarium Online

Authors: Steve Alten

Tags: #Thrillers, #Suspense, #Espionage, #Fiction

“Contact the Institute—someone you trust. I want the

AG-III

prototype crated and loaded on board my planes.”

“An Abyss Glider? Jonas, bin Rashidi has Manta Rays—”

“This is a rescue mission. I need something with a grappler arm.”

“Okay.” Mac stares at the Pacific. Swallows hard. “Jonas, David’s a good pilot . . .”

Jonas nods, choking on his words. “I’ll find him.”

Panthalassa Sea

Our planet is an interactive biomass, possessing a self-regulating homeostatic system that stabilizes global temperatures and chemical compositions—conditions necessary to sustain life.

Earth’s womb is its oceans, its vast currents the circulatory system that regulates global temperatures and provides nourishment to every living creature. While these currents are affected by wind and tides, the moon’s gravitational pull and the planet’s rotation, the real power train that keeps these planetary rivers of water flowing is thermohaline circulation. Warm water has a tendency to rise, while colder, saltier water, being denser, will sink. Density differentials in water, created by temperature (

thermo

) and salinity (

haline

) move large rivers of water just as the jet stream moves great volumes of air—

—a prime example being the Gulf Stream.

Part of the oceans’ global circulatory system, the Gulf Stream is a shallow, warm current that moves more water than five hundred Amazon rivers. Heated by the equatorial sun, the Gulf Stream rises, releasing enough heat to power the world a hundred times over. As it flows north past Florida, it is chilled by the wind, accelerating evaporation. Now saltier and cooler, the current sinks into the North Atlantic depths, replaced in turn by warm water, which follows its downward flow.

Reaching sub-polar temperatures around Greenland, the current descends to depths of six thousand to ten thousand feet, where it begins its southerly flow into the Western Atlantic Basin. Influenced by the contours of the deep ocean floor, this submarine river winds past Antarctica before flowing into the Pacific and Indian Oceans, looping into other currents before upwelling back to the surface to begin its planetary journey back in the Gulf Stream. So vast is this oceanic conveyor belt that it can take over a thousand years just to complete one lap around the globe.

The Panthalassa submarine current circulates nutrients in a similar way. Cold seeps rising from the ancient sea floor create a massive upwelling of dense, frigid water which is drawn in a clockwise easterly flow by the planet’s rotation. As this current continues east it collides with a warm influx of water created by a seismically active sea floor dominated by thousands of active hydrothermal vents. These vents, or black smokers, excrete superheated, seven-hundred degree Fahrenheit water, heavily laden with chemicals and minerals. As the heated water rises, it meets the freezing cold layer, forming a hydrothermal plume.

This swirling ceiling of dense mineralized water effectively traps and seals in the heat, creating a tropical layer below. The density differential between the upper cold layer and the tropical abyss drives the Panthalassa current like a raging river, increasing its flow rate over the next six hundred miles. As the current reaches the eastern-most point of the subterranean sea, the vents become sparse, the ocean temperatures cooling rapidly. The cooled current sinks as it flows to the south, then west, where it eventually meets the cool water seeps to begin the process all over again.

In the isolated depths of the Panthalassa Sea, the extreme differences in heat and cold that fuel the thermohaline submarine river has provided a perpetual supply of food for its prehistoric inhabitants for more than 250 million years. But the cold seeps and hot vents do far more than circulate nutrients; their vastly different temperate zones also serve to segregate its population into two very distinct food chains.

David Taylor closes his eyes as he urinates into the flexible plastic six-inch tube attached to the sixteen-ounce bottle. “Oh, baby, that feels good. My back teeth were floating.”

Kaylie ignores him, too focused on piloting the sub through the Panthalassa submarine current.

“All done here. Sure I can’t interest you?”

“I told you, I’m covered.”

“With what? Is it some kind of diaper or something?”

“When we get out of this mess I’ll let you try it on, okay. Now hurry up and finish, the current’s getting rougher.”

“You can’t rush a guy when he’s peeing. Cut it off mid-stream and you’re liable to blow out your prostate.” He moans for effect then feels the sub rising. He glances at the depth gauge.

. . . 19,175 feet . . . 18,840 feet . . .

“Kaylie, keep us level. You’re ascending too fast.”

“It’s not me. It’s the current.”

As if in response, the sub’s bow suddenly heaves upward, causing David to spill urine all over his pants before Kaylie can level them out again.

“That’s not funny!”

“I didn’t do it! I told you, it’s getting too rough for me!”

He caps the bottle and zips up, setting his hands and feet at the port-side master controls. “Switching over . . . now.” The two joysticks instantly animate in his palms, the current’s torque on the sub’s two wings registering throughout his upper torso. “What the hell? The current’s upwelling.”

“No shit. Take a look at the sea temperature.”

The gauge reads fifty-seven degrees Fahrenheit and rising.

“We must be entering a hydrothermal vent field.”

“Is that good?”

“Not while we’re still traveling in the current. The temperature differential could—”

Kaylie screams as a column of rushing water catches the Manta Ray’s wing expanse like hurricane winds peeling away a tile roof. The submersible’s bow flips straight up, continuing into a 360-degree somersault as the swirling vortex catches the wings like a sail, tossing the craft sideways, punishing the tiny submersible and its two helpless passengers.

Mercifully, the current spits them free.

The damaged sub stalls. Neutrally buoyant, it hovers upside-down in the water, its shaken occupants struggling to regain their equilibrium.

David massages his throbbing head, his brain rattling like it did after his football concussion.

Kaylie moans, “Can you at least right us before I puke?”

He fumbles at the inverted controls, managing to restart the engines. The starboard shaft grinds metal against metal, forcing him to ease off before he tears up the housing. Using only his left pedal, he rights the sub, moving them ahead at a cautious three knots. “You okay?”

“My head’s pounding, I’m seasick, my diaper’s full, and I’m scared shitless. Would you describe that as being okay?”

“Beats being dead. And if I remember correctly, I practically begged you not to come.”

“Remind me later to pat you on the back.” She searches a medicine bag for aspirin. Swallows four with a swig of icy water. “Any idea where we are?”

He checks their position. “About four miles southwest of Maren’s access hole and two miles beneath the Panthalassa crust. Can you hear anything on sonar?”

She listens over her headphones. “Only that current. It’s blotting out every ambient sound in the sea.”

“I’ll move us farther away.” David engages the port-side propeller when he sees something looming in the darkness ahead. Adjusting the cockpit’s night glass contrast, he stares into the olive-green abyss—

—then shuts down the engine, allowing them to drift.

“What are you doing?”

“Shh! Overhead and up ahead.” He points.

She looks up, gazing at swirling shadows of movement converging on a whale-size mass two hundred feet above their present location. Kaylie’s eyes adjust, allowing her to identify the ancient participants of the eastern Panthalassa food chain.

Hadopelagic krill swarm through the sea like hordes of locusts, rising up from the depths to feed on microscopic particles of food. Spiraling around a twinkling, albino cloud of shrimp are schools of anglerfish, their bioluminescent orbs swirling through the darkness like a million fireflies caught in a tornado. Dive bombing into the maelstrom are sharks, the predators moving far too fast to identify.

At the heart of the abyssal smorgasbord is an 83,000-pound Leeds’ fish.

Wounded, gushing blood from dozens of gaping wounds, the eighty-five-foot behemoth is literally being eaten alive as it attempts to distance itself from the Panthalassa

’s

true warm water predators.

A twelve-foot halosaur attacks one of the creature’s enormous ray-shaped pectoral fins. Paddling with its four limbs, the small mosasaur snaps its crocodile-like jaws upon the lashing fin and holds on, its double row of pterygoid teeth, located along the roof of its mouth, puncturing flesh and bone. Gill adaptions flap behind the ancient marine reptile’s powerful neck as it whips its head to and fro until the sixty-pound morsel rips free.

Drawn to the fresh wound is a pair of six-foot

Hybodus

sharks. Bearing a heavy upper-lobed caudal fin like the modern-day thresher shark, this denizen of the Triassic-Cretaceous period possesses a pair of devil’s horns protruding behind their eyes and a spine on the frontal tip of its split dorsal fin, the built-in weapon allowing it to ward off attacks from above. The sharks—both females—swoop in upon the Leeds’ fish, burying their blunt jaws nose-deep into a bleeding patch of pink flesh. Wiggling their entire bodies back and forth in a vicious frenzy of movement, they use their serrated teeth to chew through tissue and bone.

Moving out of the darkness to trail alongside the Leeds’ fish is the elasmosaur. Forty-five feet long, possessing a thin neck that spans half its body length, the heavy-bellied plesiosaur has targeted a gaping wound located just above the Leeds’ fish’s left pectoral fin, attracting several dozen piranha-like angler fish. Using its four six-foot-long flippers to propel itself closer to the frenzy, the elasmosaur suddenly lunges laterally with its head, its needle-sharp interlocking teeth spearing three of the angler fish from behind, scattering the rest. Retracting its head, it chomps down the mouthful of food, allowing the anglers time to regroup before it moves in to dine again.

David’s peripheral vision catches movement. Turning to his left he comes face to face with the reptilian eye of

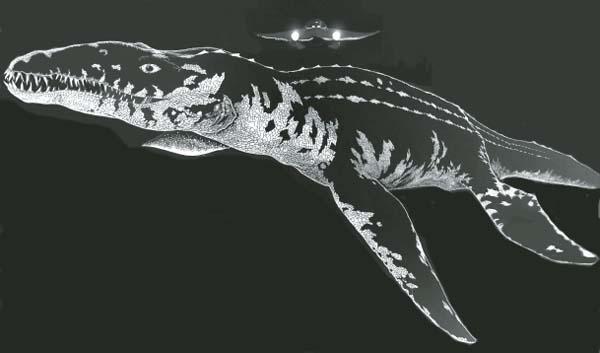

Hainosaurus.

The giant mosasaur glides by, revealing a terrifying up-close view of its fifty-seven-foot girth. Crocodile-shaped jaws that could swallow a grown man whole yield to a thick neck and stout four-flippered body, ending with a powerful twenty-foot-long, eel-like tail.

Ignoring the dormant Manta Ray, the thirty-two-ton brute circles effortlessly beneath the Leeds’ fish as it sizes up its next meal . . . and its competition—

—which arrives from above. For a heart-stopping moment David mistakes the huge bodied creature as an adult Megalodon, but as it circles the periphery he can make out not one, but two of the monsters, swimming in formation.

The female kronosaurs are smaller than the giant mosasaur, but just as dangerous. Possessing seven-foot skulls, with jaws filled with nine-inch conical teeth, the creatures’ bodies are densely muscled, from their powerful necks down to stubby, triangular tails. The monsters are swimming in synchronized fashion, the second pliosaur being towed within the wake of the first—

—

just like Lizzy and Bela!

And in that fleeting moment of clarity David understands: Among the big predators, size—or perceived size—is everything.

The lagoon’s water supply flows into the Meg Pen. Even though the tanks are physically separated by a sealed passage, the sisters can still sense Angel’s presence . . . and they fear her.

Detecting the kronosaur’s arrival, the mosasaur launches upward to claim its place at the dinner table, its mouth stretching open like a python’s—

—its jaws slamming home upon the Leeds’ exposed belly. The dying giant convulses within its attacker’s grip as the halosaur lashes its head and body back and forth until its rows of pterygoid teeth excise an eight-hundred-pound mouthful of flesh and innards.

Blood gushes from the mortal wound, bathing the mosasaur as it feeds. The creature remains close by the dead Leeds’ fish, safeguarding its kill. Heavy jowls chomp the meat into pulp, the brute’s gill slits and thick belly quivering with the effort.

And then suddenly the mosasaur swims off, abandoning the kill.

The kronosaurs are moving off, too. So are the sharks, the elasmosaur, even the angler fish—every creature vacating the kill zone.

An eerie quiet pervades.

Kaylie’s limbs tremble, the blood draining from her face. Squeezing David’s arm, she points to her sonar array.

The enormous

blip

is moving seventy feet below them, gliding in from the east.

David presses his face to the cockpit glass by his head, peering down past the portside wing, his eyes focusing on movement, his pulse pounding in his neck.