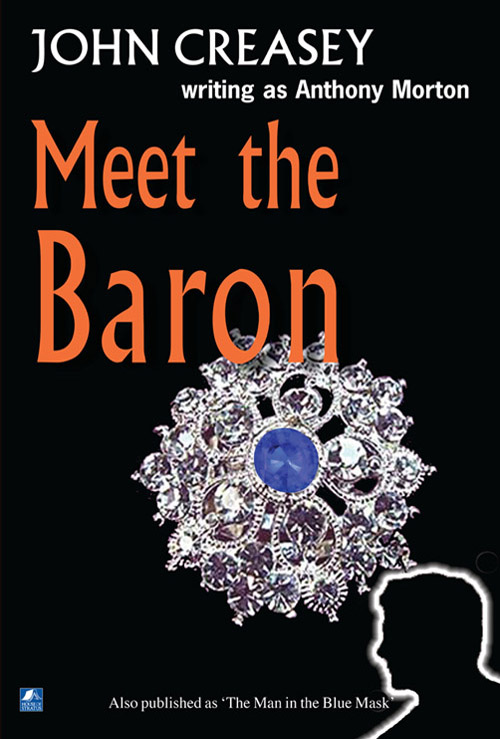

Meet The Baron

Meet The Baron

First published in 1937

Copyright: John Creasey Literary Management Ltd.; House of Stratus 1937-2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The right of John Creasey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

This edition published in 2010 by House of Stratus, an imprint of:

Stratus Books Ltd., Lisandra House, Fore Street, Looe,

Cornwall, PL13 1AD, UK.

Typeset by House of Stratus.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress.

| | EAN | | ISBN | | Edition | |

| | 0755117751 | | 9780755117758 | | Print | |

| | 0755118707 | | 9780755118700 | | Pdf | |

| | 0755125576 | | 9780755125579 | | Kindle/Mobi | |

| | 0755125584 | | 9780755125586 | | Epub | |

This is a fictional work and all characters are drawn from the author’s imagination.

Any resemblance or similarities to persons either living or dead are entirely coincidental.

John Creasey – Master Storyteller - was born in Surrey, England in 1908 into a poor family in which there were nine children, John Creasey grew up to be a true master story teller and international sensation. His more than 600 crime, mystery and thriller titles have now sold 80 million copies in 25 languages. These include many popular series such as

Gideon of Scotland Yard, The Toff, Dr Palfrey and The Baron

.

Creasy wrote under many pseudonyms, explaining that booksellers had complained he totally dominated the ‘C’ section in stores. They included:

Gordon Ashe, M E Cooke, Norman Deane, Robert Caine Frazer, Patrick Gill, Michael Halliday, Charles Hogarth, Brian Hope, Colin Hughes, Kyle Hunt, Abel Mann, Peter Manton, J J Marric, Richard Martin, Rodney Mattheson, Anthony Morton and Jeremy York.

Never one to sit still, Creasey had a strong social conscience, and stood for Parliament several times, along with founding the

One Party Alliance

which promoted the idea of government by a coalition of the best minds from across the political spectrum.

He also founded the

British Crime Writers’ Association

, which to this day celebrates outstanding crime writing.

The Mystery Writers of America

bestowed upon him the

Edgar Award

for best novel and then in 1969 the ultimate

Grand Master Award

. John Creasey’s stories are as compelling today as ever.

Lady Mary Overndon tickled the end of her long and patrician nose with a tortoiseshell lorgnette that was as old-fashioned as her bun-shaped coiffure. Thirty years before her long grey dress, with its flounces and its trimmings of fur and beads and its stiffened collar of fine muslin, might have been in the height of fashion; in this year of grace the only thing about Lady Mary in the height of fashion was her mind, and few were privileged to know much of its workings.

Colonel George Belton, her companion in the sunlit room overlooking the lawn and tennis-courts of Overndon Manor, studied her, and smiled to himself. She looked an arrogant old shrew - hard, embittered, and self-centred, as though sixty years in a fast-changing world had proved too much for her.

The Colonel laughed suddenly. Lady Mary looked at him, as he knew she would, and her grey eyes were sparkling. A man or woman of understanding had but to look into her deep grey eyes to know that her thin lips and pointed chin were lying. Her eyes bespoke humour and understanding. So did her voice - a rather slow, low voice.

“What’s the matter with you now, George?” she asked.

The Colonel smiled behind his bushy white moustache. “I was thinking,” he said, “that of all the men who’ve met you because of Marie Mannering’s the only one who’s not been scared away. There are possibilities about that man, Mary.”

“I don’t think so, George, where Marie is concerned.”

Colonel Belton was surprised, and a little disappointed. He liked Mannering, he loved Lady Mary’s daughter, and he adored Lady Mary herself His knowledge of the women, built up during the five years that he had been the Overndons’ next-door neighbour, had told him that John Mannering would make an admirable husband for Marie and an excellent son-in-law for Mary. True, none of them knew more than that Mannering was young - well, youngish: thirty-five, perhaps - handsome enough, apparently rich enough, and a member of a family as respected as the Overndons. But the Colonel had built for himself a pleasant little fairy story with a happy ending. Marie was twenty-two, and the Colonel was old-fashioned enough to believe in early marriages for women. So he scowled, and demanded an explanation.

Lady Mary regarded the two people who had just left the tennis-court and were moving across the lawn towards the Manor. The Colonel whistled to himself, for he knew that Lady Mary was sad, and for the life of him he couldn’t guess why.

“They make a handsome pair, don’t they?” he demanded doggedly. “What’s the matter with Mannering? This is the first time you’ve ever suggested anything against him. Damn it, and I - ”

“George,” said Lady Mary gently, “you talk too much.”

There were some things that Colonel Belton took hardly, even from Lady Mary. He frowned, pursed his lips, and sulked.

Mannering, dressed in white flannels that were vivid against the sunlit green of the lawn, walked easily and carried his seventy-two inches well. Lady Mary could see him smiling as he talked to Marie, who hardly reached his shoulder. His face was tanned to the intriguing degree of brown that could make even a plain man distinguished, but he would have been presentable without that. Marie Overndon was small, dainty, and lovely. Her wide grey eyes, suggestive of her mother’s, looked out on the world with confessed enjoyment; she was alive. Slim, straight, and supple, she carried herself with easy grace as she walked with Mannering towards the house.

They were within twenty yards when a ‘hallo’ came from the end of the garden, and a man and a woman hurried through a wicket gate, brandishing tennis racquets and shouting as they came.

The Colonel scowled as the couple on the lawn turned to meet the newcomers. He continued to scowl as the four went to the tennis-court for a prearranged set and were lost to sight, hidden by a thick shrubbery. He took a pipe from his pocket and began to fill it with tobacco from a leather pouch. Not until the first puff did his face clear, and at the same moment Lady Mary laughed.

“What’s the matter with you?” demanded the Colonel explosively. “Damn it, Mary - why the blazes don’t you make up your mind and marry me?”

“So that you can put in more time at your club?”

“Bah!” said the Colonel.

“I’ll marry you,” said Lady Overndon, “when Marie’s married. Not before.”

“She’s a born spinster,” snapped the Colonel, “and you do your damnedest every time a likely fellow comes along to make him realise it. Mannering’s a bit old, perhaps, as to-day’s youth goes, but that’s almost an advantage; and they’re well matched, aren’t they? And they’re as much in love with each other as - as”

“You with me?” suggested Lady Mary.

“There are times,” said the Colonel, “when I could bow-string you! Be fair, Mary. What’s Mannering done to upset you?”

Lady Mary used her lorgnette to scare a persistent fly from her small ear.

“Nothing,” she said, during the operation. “I like Mannering, George, and I can’t think of anyone I’d like better - for Marie, of course.”

“Then - then what the deuce are you driving at?”

“Shhh!” said Lady Overndon. “It’s hot, and you’ll get apoplexy - and burying you might be even more painful than marrying you. George, Mannering had a talk with me this morning.”

“About Marie?”

“About Marie - and other things. He told me that he’s worth a bare thousand a year. No more, no less.”

The Colonel’s pipe dropped to the carpet, and the start of his outburst was spoiled somewhat by his hasty recovery of the briar. He was positively bristling as he spoke.

“A - a thousand? Damn it, Mary, I thought he was - his father was rolling in it, wasn’t he?”

“His father didn’t gamble on the turf or off it.”

“And Mannering - Mannering’s lost his money?”

“Most of it.”

“Gamblin’? Horses?”

“George,” said Lady Mary severely, “there are times when I think you’ll get old long before your time. Yes, John Mannering lost most of his money. Not quite in the usual way; slow horses, yes, but not women. Or, at least, he says not, and I believe him. Five years ago he reached his safety-line, left himself with capital enough to bring in a thousand a year, and retired into Somerset, where he plays cricket, rides when he can, reads a great deal, and is happy. He has a seven-roomed bungalow, one servant, two acres of land, and two horses. I’m telling you in his own words.”

The Colonel was breathing hard and scowling.

“He - he told you all this, and you - you told him to . . .”

“Are you reminding me I’m a Victorian mother, George? I didn’t tell him to go back to his bungalow; you ought to know me better.”

Colonel Belton heaved a great sigh, and smiled at last.

“Sorry, m’dear. I couldn’t see you in the part. Yet - you say there’ll be no marriage? Money isn’t so important. It’s a love match, and quite a lot of people can live on a thousand a year, or so I’ve heard. He could give up things - one of the horses,” added the Colonel, as a man inspired.

“I suppose a wife would be worth even that sacrifice,” said Lady Mary gently. “Well, now you know as much as I do, George. And I don’t think they’ll marry.”

“But that makes Marie a regular little - dammit - gold-digger!”

“Call it the wisdom of her age,” said Lady Mary. “I think I’m glad. Mannering and money could make her happy, but Mannering without it couldn’t. I may be wrong, of course, but we’ll see.”

“My opinion,” said George Belton, a little bewildered, “is that you’re talking through your hat.”

“And I’ve already said more than the modern hat could possibly cover,” said Lady Mary. “Let’s find some tea.”