Meditations on Middle-Earth (19 page)

Read Meditations on Middle-Earth Online

Authors: Karen Haber

Tags: #Fantasy Literature, #Irish, #Middle Earth (Imaginary Place), #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Welsh, #Fantasy Fiction, #History and Criticism, #General, #American, #Books & Reading, #Scottish, #European, #English, #Literary Criticism

The only meanings Tolkien cares about are the meanings

within

the story, not extraneous to it. These devices are present in the story for the story’s sake. There is no Freudian imperative to put new names on them in order to understand them. Tolkien has given them their right names from the start; and when he does switch names, it is for practical, not literary, reasons—Aragorn is also Strider, Saruman is also Sharkey, and Smeagol is also Gollum—because their role in society changes in the process of the story, and the revelation of identity is meant to revise the meaning of the story to its

participants

as well as to the readers. Those revelations change the meaning of the story

within

the story, and not just in English class.

There are literadors who recognize this, but regard it as a reason to treat Tolkien’s work as “subliterary.” Because it does not lend itself to being operated on with the tools of the trade, Tolkien’s oeuvre is not worthy of treatment as serious literature. And, apart from the value judgment inherent in this attitude, they are correct. If by “serious” literature, you mean literature whose meaning is to be found upon the surface of the story like an exoskeleton, to be anatomized without ever actually getting into the story itself, then Tolkien’s work is certainly not “serious.’

What Tolkien wrote is obviously not “serious,” but “escapist.”

Those who read “seriously” have no possibility of escape. They are never inside the world of the story (or at least cannot admit it in their “serious” discussion of it—God forbid they should be caught committing the misdemeanor of Naive Identification). They remain in their present reality, perpetually detached from the story, examining it from the outside, until—aha!—the sword flashes and the literador stands triumphant, with another clean kill. It is a contest from which only one participant can emerge alive.

“Escapist” literature, on the other hand, demands that readers leave their present reality, and dwell, for the duration of the story, within the world the writer creates. “Escaping” readers do not hold themselves aloof, reading in order to write of what they have found. Escapists identify with protagonists, care about what they care about, judge other characters by their standards, and hope for or dread the various outcomes that seem possible at any given moment in the tale. When the story is over, escapists are reluctant to return to the prison of reality—so reluctant that they will even read the appendices in order to remain just a little longer in a world where it matters that Frodo bore the ring too long ever to return to a normal life, that the elves are leaving Middle-earth, and that there is a king in Gondor.

So there we have it: “serious” literature is a complicated business, requiring experts to extract meanings, while “escapist” literature is so simple it needs no mediation.

Wait. That’s not how it works at all. On the contrary, “serious” literature is so simple that it can be decoded, its meanings laid out in essay form, while “escapist” literature is so complex and deep that it cannot be mediated, but must be experienced; and no two readers experience it the same.

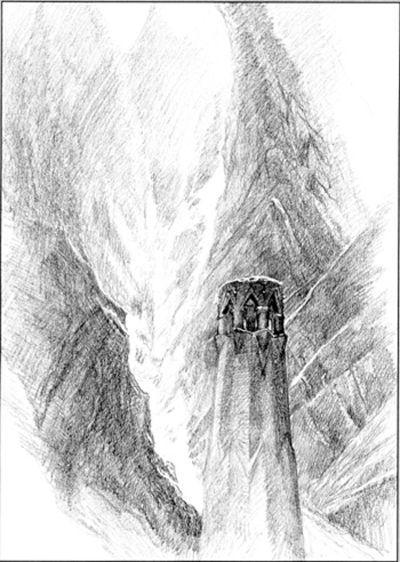

AT HELM’s GATE

The Two Towers

Chapter IV: “Helm’s Deep”

That is the great secret of contemporary literature, that to write with “meaning” in mind simplifies a story. Consciously created symbols and metaphors silt it up until it is only a few inches deep, and you can find the fish as they flop around, and pick them up with your bare hands. But those stories written without an extraneous meaning run fast and deep, and those who dive in and are carried along by the current can never, as they say, step in the same river twice.

The Sirens chapter is always the Sirens chapter, every time you read it. But the Inn at Bree is never the same place for any two readers, or even for the same reader at different times.

Oh yes, right, I know: those who love

Ulysses

find new wonders in it every time they read. To which I say, cool. Read it again and again, you lucky Smart People; you really have it over the rest of us poor peasants who find it to be one long tedious joke, which isn’t very funny because it has to be explained. Pay no attention to us as we close the door to your little brown study and get back to the party.

My point is that

Ulysses

can be taught. But The Lord of the Rings can only be read. When someone takes you through

Ulysses

and discusses it in serious literary terms, you constantly get the pleasures of a cryptic crossword puzzle: Ah, so

that’s

why this chapter was so unintelligible! But when you discuss The Lord of the Rings, each explanation takes you, not farther into the text, but farther out of the story. Instead of “aha!” you keep thinking “is that all?”

Here’s why: “escapist” reading is by nature wild, while “serious” reading is by nature domesticated.

“Serious” reading is designed to bring readers to a common experience

outside

the story, by writing papers that attempt to persuade others that

this

is the (or a) “meaning” of this or that item in the tale (or attribute of the text).

But “escapist” reading brings readers together only when they are

inside

the story; and the more closely they compare notes, the clearer it becomes that they have not had the same experience, not in detail.

This is not simply because readers inevitably come up with different visualizations of the characters and milieux—for the same difference between “serious” and “escapist” can be found in the ways people make and watch movies, which forbid you to engage your visual imagination.

Rather, “escapist” readings vary so widely because the story is not the text. Rather the text is the tool that the readers use to create the story in the only place where it ever truly exists—their individual memories. Because the writer has provided the same tool to all readers, the stories in their memories will resemble each other, sometimes very closely. Can we conceive of any reading of The Lord of the Rings that does not have the Gollum biting off Frodo’s finger, and falling, finger, ring, and all, into the fires of the Cracks of Doom? But haven’t we all had the experience of discussing the story with someone else and having him or her refer to some moment, some event, that we had forgotten, or never noticed, or—and this happens surprisingly often—that is absolutely contradicted by our own clear memory?

Readers, in fact, make a jumbled mess of their reading. Like eyewitnesses who only remember what they noticed, and only notice what seems important enough to command their attention at the time, readers edit unconsciously as they go, linking moments in this present story to moments in other stories that were inadvertently called to mind. (How many times have I heard readers praise or complain about a particular scene or phrase or event that simply does not occur in the book in which they say they remember it?) What reader, upon rereading a particular story, especially after an interval of several years, is not surprised to discover that

this

scene is in the same story as

that

scene?

When readers are not “serious,” but rather are deeply, personally, and emotionally involved in a story, the story is transformed to at least some degree by their preexisting view of how the world works. They do not realize it at the time or, usually, ever. They

think

the story they love so much is Tolkien’s story. But in fact it is a collaboration between the-Reader-at-This-Moment and Tolkien-at-the-Time-He-Wrote. Tolkien is the author: when there are disputes about what happened in the story, it is to Tolkien’s text that disputing readers must return, with no extraneous commentator having even the slightest authority. But except for those rare moments of controversy or of the cognitive dissonance of rereading a familiar tale that turns out to be unaccountably strange, readers remain unaware of how they have transformed the tale.

Similarly, readers are rarely aware of how the tale transforms them. For that is the power of “escapist” (but not “serious,” or seriously read) fiction: The events of the story, their causes, their results, their meanings-within-the-tale, enter into the readers’ memory in a way that is ultimately only somewhat distinguished from “real” memories. In part, this is because “real” memories are in fact “storyized” whenever they are recalled or recounted, so that “real” memories become more certain even as they become less correspondent with the actual experience. But “escapist” readings gain most of their power to transform the readers’ worldview from the very authority of the author.

While we live in Tolkien’s world, it is with almost unbearable pain that we watch Gandalf fall to his death, locked in the embrace of the Balrog, or see the damage Sharkey and his gang have done to the once-lovely Shire. We have no doubt that Shelob must be stopped, not because she is part of Sauron’s evil plot, but simply because she is in the way. We are allowed some pity for her, but Frodo

must

be freed. This is a morally complex issue, in fact. The more we examine it, the more our sympathy for Shelob increases. She isn’t trying to rule the world, she’s merely trying to eat. Isn’t she in the category of the shoplifter who steals food because he’s starving? Well, not quite—after all, her idea of a snack is Frodo, not a bag of Oreos. But to her, what is Frodo but lunch on the hoof? He is not of

her

species. If he gets stuck in her web, he’s meat. What has she done that makes her worthy of death? And yet whatever pity we feel on first or second or third reading, the fact remains that we want her to fail; and because she is so relentless, the only way she can fail is to suffer incapacitating injury, and so we are relieved when she is hurt and retreats to her lair to suffer the agonies our heroes have inflicted on her.

This is a complicated process, and it is quite possible that Tolkien is creating or reinforcing an immoral morality. That is, if you subscribe to the worldview of the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), obviously, Shelob is an innocent victim, and The Lord of the Rings supports an evil anthropocentric view of the animal kingdom, in which humans (or ur-humans) have the right to intrude wherever they want and kill or hurt whatever animals happen to get in the way.

Yet there is no room within the experience of the story to argue with Tolkien. The Lord of the Rings is not an essay, whose tenets are to be consciously considered. It is a story, plain and simple; and if during the Shelob passages your deep morality is offended, the effect is not an argument, but rather a withdrawal from the world of the tale. You close the book—perhaps you throw it against the wall. Or perhaps you grit your teeth and return, because the rest of the story is so good that you’ll just have to ignore the mistreatment of Shelob and move on.

That’s what happens when a story is

so

foreign to our own worldview that we cannot accept it. The Escape is over. We are forced to return from the story because we cannot bear to live in the author’s world any longer.

Often, we cannot name our reasons. It is nothing so plain as a PETA member’s reaction to the Shelob story. Rather, we find our attention wandering when we try to escape in a story whose world is unbearable to us. Or we find ourselves losing our willingness to suspend our disbelief. Or we simply don’t understand what’s happening—we can’t process the story, because the characters’ actions don’t make sense to us.

That’s why stories can never be wholly transformative. The author makes things happen in a tale for reasons that are only sometimes consciously understood. But having created the story, having offered it to the public, the author may find that many people read it with enthusiasm, while a few find it tedious, unbelievable, incomprehensible, or even evil. The same book! So variously, even perniciously misread! But it is the simple result of the fact that no two individuals actually live in the same world. Oh, we think we do—we have conversations and share food and bicker and so on—but nothing ever means exactly the same thing to any two participants in an event. (Note that I’m referring to meaning-within-the-tale, though in this case the tale happens to be reality.) And even when we explain our view and achieve agreement, we have to admit that even our agreement has a different meaning to each and every person who agrees to it. We may agree that we agree, but in fact we do not fully agree.

All stories have to offer some common ground to at least some readers—some aspect of the worldview of the tale that feels true and right. Without that, the readers cannot escape into the tale for long. Indeed, my guess (though it cannot be measured) is that the vast majority of causal and moral assertions in the tale must already be shared by the storyteller and the culture that produced the readers who embrace it; it is within this flood of agreement that the author’s unique (and therefore strange-to-the-readers) views are able to slip through unnoticed, subtly but often significantly changing the way the readers see the real world that they return to when the Escape has ended.