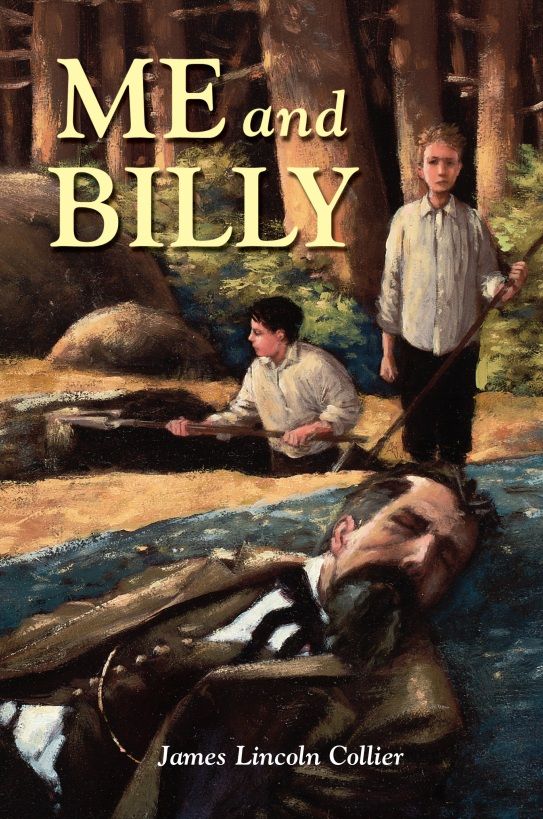

Me and Billy

Authors: James Lincoln Collier

ME

and

BILLY

and

BILLY

James Lincoln Collier

Text copyright © 2004 by James Lincoln Collier

All rights reserved

Amazon Publishing

ATTN: Amazon Children’s Publishing

P.O. Box 40080

Las Vegas, Nevada 89140

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Collier, James Lincoln, 1928-

Me and Billy / James Lincoln Collier.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: After escaping the orphanage where they have spent their lives together, two boys become assistants to a con artist, and while Possum objects to the lying, stealing, and cheating, Billy only cares about making money and taking life easy.

ISBN 0-7614-5174-9

[1. Swindlers and swindling—Fiction. 2. Orphans—Fiction. 3. Runaways—Fiction. 4. Best friends—Fiction. 5. Friendship—Fiction. 6. Conduct of life—Fiction.] I.

Title.

PZ7.C678Me 2004

[Fic]—dc22

2003026865

The text of this book is set in Goudy.

Book design by Patrice Sheridan

First edition

1 3 5 6 4 2

For Harry

Chapter One

Me and Billy liked to get Cook to talk about how things were on the outside, beyond the high brick wall that went around the Home. We boys hardly ever got out past the walls to see for ourselves. Once a year, on Fourth of July, the Charity Ladies, who put up money for the Home, took the boys to some lake to see how many of us would drown. At Christmas they’d take us over to the Girls’ Home for a party, where the boys didn’t do anything but fight and throw food.

That was about it. We didn’t have any clear idea of how things were in the outside world. It was a mystery to us. We knew there were such places as stores, where you could buy apples or honey and things if you had some money; but we never had any money, so stores didn’t matter much to us. We knew that boys out there

had bicycles to ride on, baseball bats, and sleds to slide down steep streets on in the winter, for we read stories about boys doing such things in our reading books. But we didn’t know what it felt like to ride a bike or slide down a street on a sled. Anyway, we weren’t sure that we could do these things even if we got outside ourselves. Maybe boys who grew up in Homes weren’t allowed to have bicycles and sleds. We didn’t know.

But Cook had spent most of his life, until the last ten years, outside the Home, and he still went out every Sunday afternoon to visit an old widow woman he was soft on. Cook liked boasting about all the things he’d done other places, and we encouraged him, for we were mighty curious about the outside world. When me and Billy were sent into the kitchen to scrub pots and pans, we always got Cook talking about such things if we could.

We switched off, one washing, one drying. This time, as soon as we got a few pots done so it looked like we were being industrious, Billy said, “Cook, you ever know any rich people out there?” We knew he’d say he had, whether he had or hadn’t. We liked hearing about rich people.

Cook was stirring a big pot of beans. “Sure. I knew plenty of them rich. When I was out there in Californy back a while, workin’ in this here hotel, them rich men was a dime a dozen.”

“How’d they get so rich, Cook?” Billy said. I knew he was trying to figure out some way to get himself rich.

“Diggin’ for gold.” Cook looked around to see if we believed him. We knew enough to look like we did. “Was layin’ around all over the ground out there in them days. I know—I seen it. I seen a whole lake fulla gold once. Up in some mountains.” He turned back to stir the beans.

“A lake full of gold?” I said. A lot of things Cook said were hard to believe, but this was harder than most. “Where was the gold, just floating around in the water?”

“Gold doesn’t float, you dummy,” Billy said.

“You don’t know as much as you think you do, Billy,” I said. “Maybe there’s some kind of gold that floats.”

Cook looked around at us. “Neither of you know nothin’ about it. I seen it. You didn’t.” Cook was wearing a dirty undershirt. He was getting stooped from being old and didn’t shave but once a week when he visited the widow woman he was soft on.

“Well, then, where was it?” Billy said.

“Bottom,” Cook said. “Gold all over the bottom of that there mountain lake. Great big chunks of it. Some of ’em big as your fist.”

Well, I wanted to believe it. It was nice to think that there might be some gold out there somewhere I could have just for picking it up. But it wasn’t an easy thing to believe. I gave Billy a glance to see what he was thinking. His eyes were wide and shining, and I knew right away there was going to be trouble. He said, “Why didn’t you dive down and get some?”

“You ain’t callin’ me a liar are you, Billy? I wouldn’t if I was you.”

“No, no, Cook,” Billy said. “I believe you.” If Cook thought you doubted his word he’d clam up on you and then there’d be nothing for entertainment but scrubbing pots. “I wasn’t calling you a lair.”

“You ain’t in any position to call no one a liar, Billy Foster,” Cook said. “Keep it in mind.”

Cook was right about that. Billy was the blamedest one for lying. He could think up lies faster than most people could talk—mix in some facts here and there to throw you off and give it flavor—and before you were finished, he’d have you believing that snow was cream cheese and pigs could fly. Leastwise he’d have the boys believing it. I don’t guess Billy got a whole lot past Deacon and his sister, who ran the Home: not much got by them. But he could put it past the boys. Me, I was different—just not a natural hand for lying the way Billy was. I didn’t have a feeling for it, was likely to blurt out the truth before I caught myself. Not Billy. Oh, the boys just admired Billy so for the lies he’d tell to Deacon or his sister or Staff. Where if a boy dropped a plate and broke it, he’d say it was because some other boy jogged his elbow. Not Billy; that wasn’t original enough for Billy. Instead he’d say that it was the cat’s fault. For when one of the boys started to sing, the cat took fright, leaped for an open window, and when Billy reached out to save it from an awful death, why it was natural that the plate would fly out of his hands and break. Or if

Billy stole a couple of doughnuts off Deacon’s breakfast tray, and they happened to slip out from under his shirt while he was carrying the tray up, he’d wheel around and shout, “What blamed boy threw those doughnuts?” even if there wasn’t anyone around big enough to throw a doughnut that far. The boys just loved to hear Billy tell stories, for Billy didn’t mind what he said to anybody; and if he knew he’d got a good audience of boys listening, he’d roll along until Deacon or somebody stopped him. Of course it didn’t ever do him any good. In the end Deacon or Staff or whoever it was would say, “I never heard such a natural-born liar in my life, Billy Foster,” and wallop the tar out of him.

So that’s what Cook meant when he said that Billy wasn’t in any position to call anyone a liar. He said, “I wasn’t calling you a liar, Cook. I was just curious is all. Why didn’t you dive down and get some of that gold?” Billy was up to something.

Cook calmed down. “Couldn’t swim,” he said. “Still can’t. Never learned how. Durn funny thing, too. I was raised up close enough to a creek so’s I could spit into it from the henhouse roof, and fished in it every spare minute I got. Never got the hang of swimmin’. The other kids all swum in that there creek, but the first time I tried it I sunk like a stone and had to be hauled out cryin’ and splutterin’. It kinda discouraged me. Never tried it again. Once was enough.”

Billy gave Cook a look. “Where was this lake? Out in California?”

“Nope. Over there somewheres past Plunket City. Was workin’ on the railroad at the time.”

I didn’t know where Plunket City was, but I’d heard Staff mention it, so I knew it couldn’t be too far off. I figured I’d better get Billy off Plunket City and that lake of gold before he got too hot about it. “I guess somebody’s come along and cleaned that gold out of there by now,” I said.

“Doubt it,” Cook said. He lifted a wooden spoon full of beans from the pot and touched them with his tongue to see if they were getting hot. Beans were the usual supper at the Home. Cornmeal mush for breakfast, bread and molasses for lunch, beans and fatback for supper. Black coffee so bitter you could hardly swallow it. Deacon Smith said we were orphans and didn’t deserve any better—no milk for the coffee, no ketchup for the beans, no jam for the bread.

“See, Possum?” Billy said “That gold’s still there.”

“What makes you think so?” I said.

Cook gave me a look to see if I was calling him a liar this time. Then he said, “Can’t nobody find the durn place. Way I heard it, some fella I was workin’ with on the railroad in Plunket City told me he brought a chunk a gold big as a baseball outta there. Didn’t have it no more. Lost it to another fella in a poker game. There was heaps of it still up there, this fella said. I went on up into them mountains with nothin’ but a jackknife, loaf a bread, hunk a cheese. Got myself lost the first day. There’s somethin’ queer

about them mountains. Turn a corner and suddenly you’re someplace else and can’t find the way back you come. Never seen nothin’ like it.”

I knew blame well that Billy wanted to run off from the Home and find that gold lake. Boys ran off now and again. You’d suddenly realize that so-and-so wasn’t around anymore. But mostly it was older boys—fourteen, fifteen. Me and Billy weren’t but twelve, thirteen, depending on when our birthdays were. We’d come to the Home at about the same time. Were babies together in the same crib, slept together in the same bed after that—two to a bed was the rule there. Pretty much did everything together all our lives. Sometimes it seemed like I knew what Billy was going to think before he did.

But Billy knew how old he was, and I didn’t. Mostly when a kid was brought to the Home, whoever brought him knew the facts of him—when he was born, who his folks were. Deacon wasn’t allowed to say who your folks were. There was some law about it where nobody was supposed to know that you’d given your baby away to a Home. But usually you’d get a name and a birthday out of it, at least.

Not me. They’d found me on the doorstep in a snowstorm curled up in a basket like a possum. No note with me to say when I’d been born, or even if I

had

been born, although I figured I must have been. So far as papers went, I didn’t exist. So I didn’t have a birthday. But the fact was I

did

have a birthday, for I

gave myself one. I knew it had been winter when I’d been left off in the snow, so I gave myself February 22, George Washington’s birthday. It worked out pretty good, for George Washington’s birthday was a holiday with no school, bands playing, and most people eating pie and cake, leaving aside orphans and such. I could pretend the holiday and the bands were for me, not George Washington, who’d been dead a good while and wouldn’t miss it. Of course I didn’t tell anyone it was my birthday, for they’d of teased the pants off me. I didn’t even tell Billy. I kind of wanted it to be a secret for myself.

So I didn’t know exactly how old I really was, but I knew we were too young to run off from the Home. “That’s it, then,” I said. “You couldn’t find that lake if you were paid for it.”

Billy didn’t pay any attention to that. “Tell us how you found it, Cook.”

“Stumbled on it. Wandered around up there two or three days half starved to death, tryin’ to find my way down out of there. Lookin’ for berries, birds’ eggs, anything. I’d of et a live rat. Pushed along till I come to some kind of meadow. Right in the middle of this here meadow was this little lake. Even at that distance I could see it sparkle. Wasn’t thinkin’ about no gold. Figured there might be fish, frogs, turtles in that lake. Jumped over to it mighty fast, you bet. Water clear as glass. Could see straight down six, seven feet. See everythin’ down there plain as day—sand, weeds, and

sittin’ on the sand among them weeds was chunks of gold. All over the bottom.”