Mayor for a New America (15 page)

Read Mayor for a New America Online

Authors: Thomas M. Menino

“They're looking in the classroom, but they really need to look in the home,” he said, surfacing a hard truth about the struggle for the schools. “A lot of the kids who have problems at school have problems at home. But they can't reassign the parents, so they reassign the teachers.”

A young woman, also a senior, “was shocked that the Burke was listed as underperforming. I thought, so what does this mean for me? That I am not prepared for college?” Echoing the cheerleader in 1996, at the start of the up-and-down story of the Burke, whose hopes for a scholarship crumbled when the Burke lost its accreditationâechoing the same anxiety about her future as that cheerleader, she asked, “Will the college admission people think twice before accepting me?”

A sign on Tom Payzant's desk read, “What have I done for children today?” The answer is: Not enough. We did not do enough for that young woman. We did not do enough for the young man. It would be small comfort for them to know that weâthe people of this rich and powerful countryâwanted to do more. We just didn't want it enough.

Â

“

I'M NOT A FANCY TALKER

”

Â

That was the first sentence I spoke as mayor in January 1994. I was following Tip O'Neill's advice to hang a lantern on your troubles. I couldn't hide my speech troubles if I wanted to.

I'm not unique in American politics. I once read a parody of President Eisenhower delivering the Gettysburg Address that begins, “I haven't checked the figures, but eighty-seven years ago, I think it was, a number of individuals organized a governmental set-up here in this country, I believe it covered eastern areas . . .”

Among mayors, Chicago's Richard J. Daley was a gaffe machine who once praised “Alcoholics Unanimous” and for “tandem bicycle” said “tantrum bicycle.” Stan Laurel, of Laurel and Hardy, milked a career of laughs from doing that: “suffering from a nervous shakedown.”

“Shakedown” is a “malapropism,” for “Mrs. Malaprop,” a character in an English comedy who uses the wrong word in place of the right word with a similar sound. I've been called “Mayor Malaprop.”

In private conversation I'd usually speak clearly. But put a microphone in front of me and I might say things like “The principal reserves the right to install mental detectors” or “He's the best public service I know” or “We can't just sit in our hands.”

“Fred Flintstone. Barney Rubble. And âMumbles' Menino makes three,” columnist Dave Nyhan once wrote, capturing my voice. In my thick Boston accent “Mayor” was “May-uh,” “Commonwealth” “Cawmulth.” And I talked out of the side of my mouth. So even when I spoke correctly, I sounded wrong. When I called the lack of parking spaces in Boston “an Alcatraz around my neck,” I sounded like Stan Laurel. People didn't feel cruel laughing at me for these howlers because I laughed at myself.

Â

Over my twenty years in office, Boston's teams won three World Series, three Super Bowls, one NBA championship, and one Stanley Cup. I was frequently called on to salute our local heroes. I did it my way.

Describing a key Red SoxâYankees playoff battle in 2004, I said, “Davy Roberts stole second base, Mueller hit the double, got him in, then Ortiz won the game. . . . There's so many . . .” I was doing great; then I wandered down memory lane: “Jim Lomborg had the great year he had.” Except it was Lonborg, and he pitched for the 1967 Red Sox.

“There's a lot of heart in this team, let me just tell you,” I said about the 2012 Celtics. “KJ is great but Hondo is really the inspiration. Hondo drives the team.” I meant “KG,” for Kevin Garnett, and Rajon Rondo. Memory lane again: “Hondo” was the nickname of Johnny Havlicek, who drove the great Celtics teams of the 60s and 70s.

A press release from City Hall hailing the Bruins for winning the 2011 Stanley Cup would have been ignored. But when I called the Bruins “great ballplayers on the ice and great ballplayers off the ice,” it made news.

An embarrassing moment came during a media event for the 2012 Patriots. They were facing a playoff against the Ravens, and I was on the phone betting a lobster on the Pats with the mayor of Baltimore. I said I expected great things from quarterback Tom Brady and nose tackle “Vince Wilcock.” Except that his name is Wilfork. Close? Yes, but I was wearing his jersey. With his name on it.

Â

“Menino's Greatest Feat: He Can't Talk About Sports,” read a Boston Magazine headline. Feat? In sports-mad Boston my “often comical ignorance about its sports teams and most popular players” didn't hurt me with voter-fans. I left office with an 83 percent approval rating (“Menino More Popular Than Kittens”) because people judged me on the condition of the city, not on the slips of my tongue.

The truth is, I rarely watched sportsâor anything elseâon TV. I focused all my attention on the city. Asked about the size of the city budget, Kevin White would make up a number. I knew it to the dollar. Instead of watching sports, maybe Bostonians sensed I was watching out for them. And as my doozies piled up, some observers wondered whether “Menino's . . . comical ignorance” of sports was more comedy than ignorance. The Globe's Shirley Leung voiced a growing suspicion: “Menino . . . played us masterfully, knowing a slip of the tongue could generate headlines and sound bites.” I kept 'em guessing.

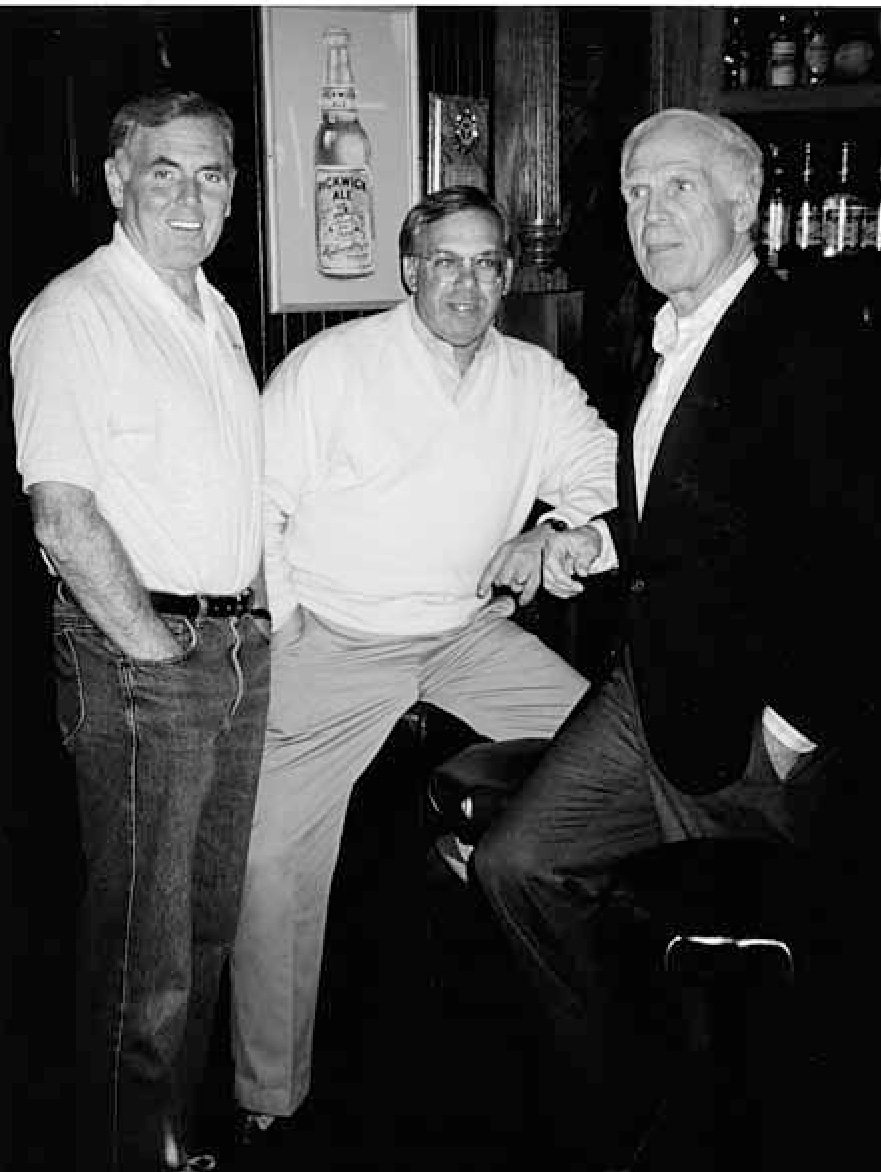

Courtesy of the Menino Family

Â

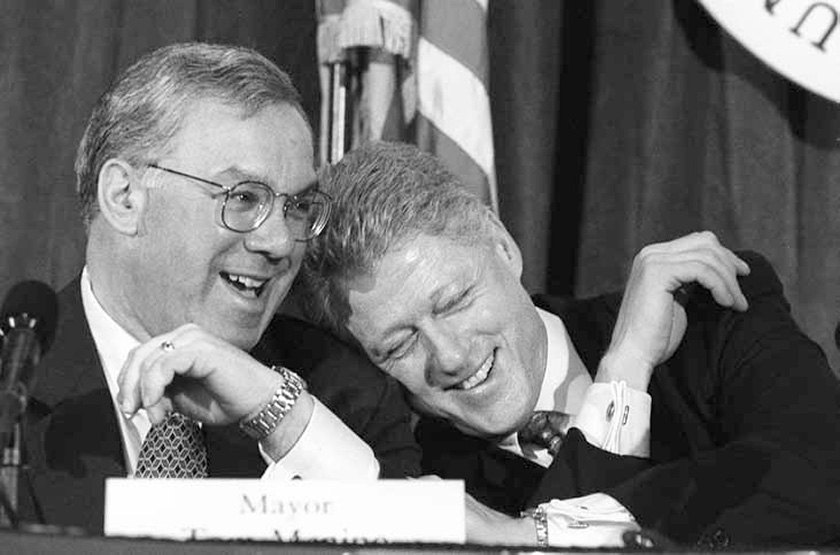

Joanne Rathe

/The Boston Globe/

Getty Images

Â

John Tlumacki

/The Boston Globe

/ Getty Images

Â

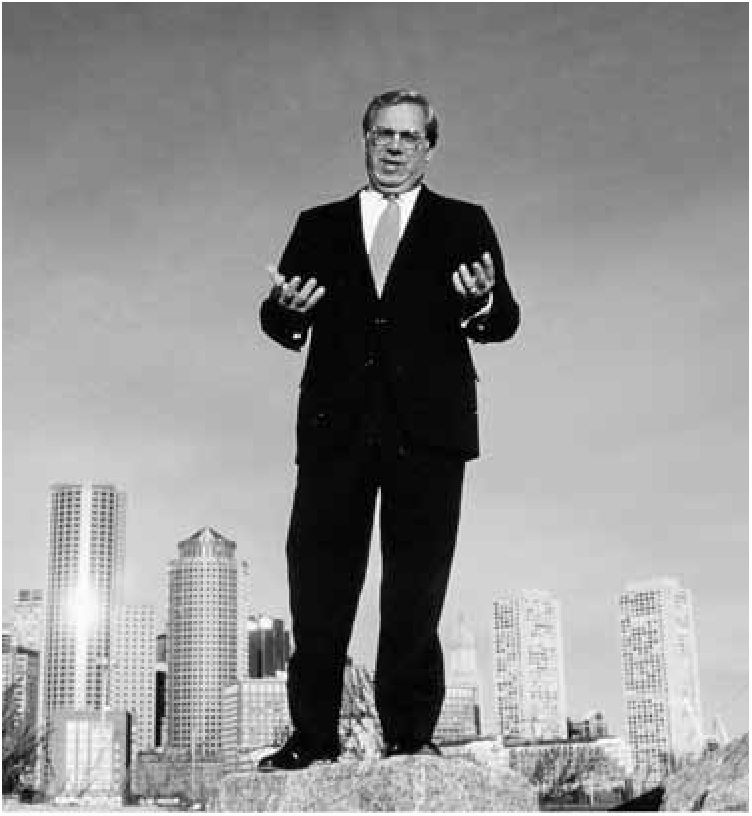

Boston Globe Magazine's

December 4, 1994, cover story: “Boston's Urban Mechanic: Can Mayor Menino's Nuts-and-Bolts Approach Revive the City?”

Bill Greene

/The Boston Globe

Â

Courtesy of the City of Boston

Â

With my friend Bob “Skinner” Donahue on the night we won the referendum for an appointed school committee, November 1996.

Michael Robinson-Chavez /

The Boston Globe

/ Getty Images

Â

© Don West Photography