Maude Brown's Baby

Read Maude Brown's Baby Online

Authors: Richard Cunningham

M

AU

DE

BR

OW

N’S

BABY

~~~~~

a novel

by

Richard Cunningham

MAUDE BROWN'S BABY

Copyright

2012 by Richard Cunningham

All rights reserved

Cunningham Studio

Houston, Texas

USA

HISTORICAL NOTE

The hurricane that struck the island of Galveston, Texas on

September 8, 1900, claimed up to 10,000 lives.

It

remains the worst natural disaster in U.S. history.

Maude Brown's Baby

is a work of fiction that follows the life

of an aspiring

photojournalist in the fall of 1918.

While much of the historical setting is real, the people in this story

live only in the writer's imagination.

etter

Tuesday, September 11, 1900

John Sealy Hospital, Galveston

, Tex.

My dearest Ida Mae,

No doubt you have read accounts of the horror that transpired here Saturday last, but words can not convey the dreadful calamity that has befallen our beautiful island city. How grateful I am that my little family is safe in Fredericksburg! Please make no attempt to return here, my love, for all is in ruin. For now, may it ease your mind to know that I am safe and still working as best I can here at the hospital, which was greatly damaged by the storm.

Forgive me if my thoughts ra

mble. I have slept less than six hours in three days. Five doctors and a dozen nurses arrived from Houston this morning, so our staff has finally some relief. We are all beyond exhaustion, but I wanted you to know that I am alive and will come to you as soon as conditions allow.

I hear that our home is badly damaged, although I have been unable to see it for myself. Was it just Saturday morning when I was last there? It seems so distant now! I arose at dawn, dressed and shaved. I had no desire to linger, the house being so void of life without you and the children, so I hurried to our little corner restaurant for breakfast. Already the clouds were darkening. I carried an umbrella, and by the time I had finished eating, a light rain had begun.

My morning was routine. I saw three patients, all with minor complaints, and dispensed some pills. One man had passed during the night, Mr. Hixson. You may remember his wife, Leona.

As I was completing my report, I noticed from my window that water had accumulated several inches deep in the street. I recall thinking it odd that a carriage rushing by created a wake large enough to push water onto an adjacent lawn.

Around noon, a new patient reported that breakers had wrecked buildings on the gulf side of the island. Having finished my report, I decided to venture out for lunch before the weather grew worse. It would be my last meal for two days! At the restaurant I learned that the street cars had stopped running, and that a section of track along the beach had washed away.

When water began seeping into the restaurant, the proprietor said he was closing for the day, so I returned as quickly as possible to Sealy. Walking was difficult as the wind had picked up, and water was soon above the tops of my rubber boots!

The electric lights went out before the worst of the storm. We struggled by candle light and lanterns to move patients away from the windows, and it is good that we did. All but six were smashed by debris carried by the terrible wind.

Around 8 p.m., water from the bay and from the gulf met, and the entire island was at once submerged. Morning revealed that miles of land and buildings were simply gone. What remains are great walls of wood and steel, boats, trees, wagons, furniture and every possible item of daily life, along with those who owned them.

It sickens me now to look outside. Another corpse wagon just passed, with two men walking silently beside. Their frightful cargo is the third I have seen today. The newspaper says 6,000 are dead in Galveston alone, and many more up and down the coast.

It has been impossible for me to grasp all that has happened here. I suppose our minds work that way to protect us, but one small thing has occurred that, at least for me, reveals the face of this disaster.

On Saturday, upon returning to the hospital from the restaurant, I was standing at the entrance pouring water from my boots when a woman clutching a baby rushed by me through the door. I followed and found her pleading with a nurse.

The poor woman’s clothes were soaked through. Her hat and combs were gone, her long hair matted about her face. She was sobbing, trying to explain that she had been caught out when the street cars stopped running. She had another child nearby and needed to reach her, but was afraid she could no longer manage the rising water with a baby in hand. Would the nurse please keep him until she returned?

Without waiting for an answer, she thrust the baby in the nurse’s arms and wheeled for the door. She stopped abruptly, took a photograph from her handbag and pressed the card between the folds of the child’s blanket. As she raced out she cried, “I’ll be back!”

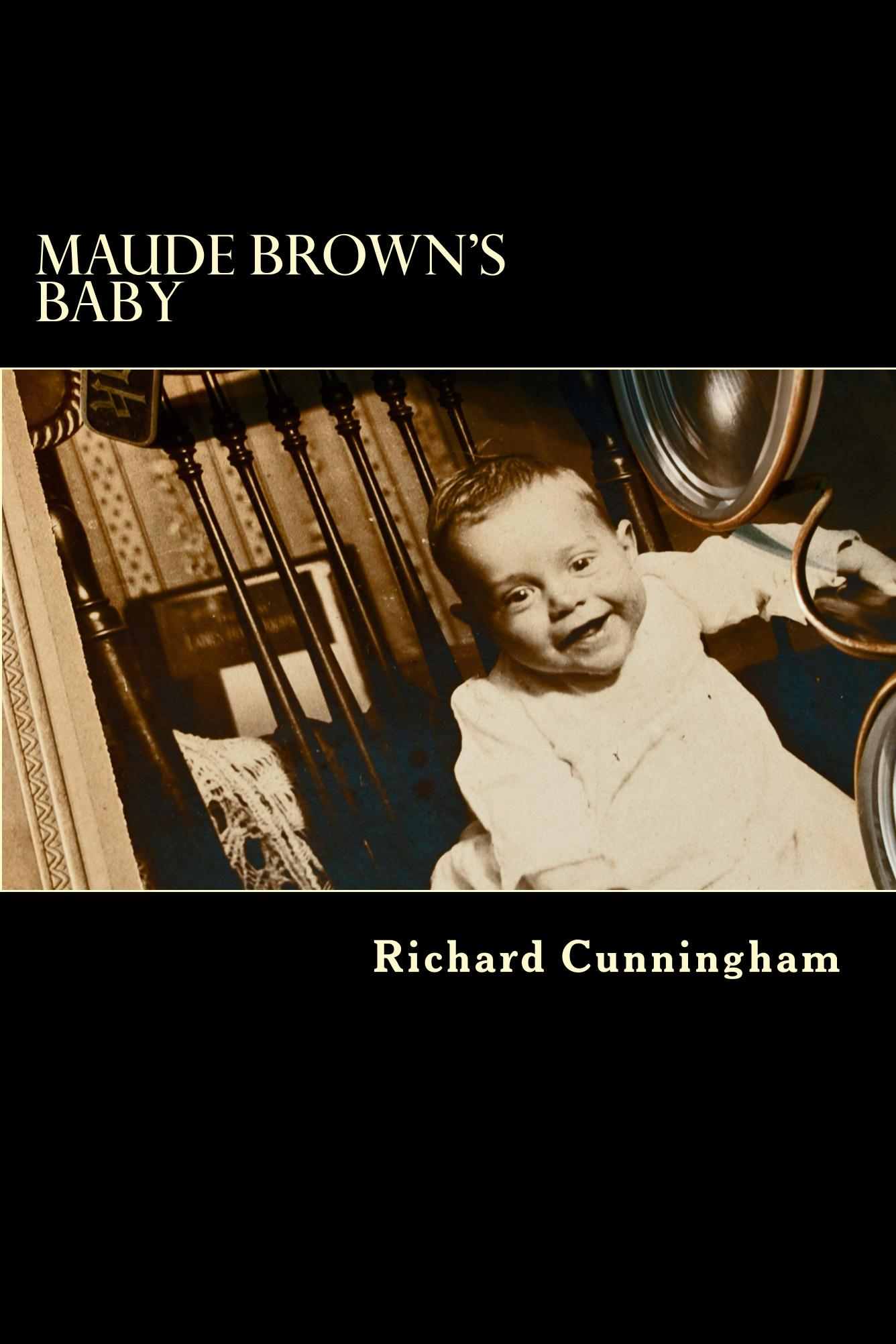

That was three days ago, so I fear the young woman perished in the storm. The child is healthy and cheerful enough, and he has become the delight of the staf

f. The photograph is of the boy—the nurses have named him Donald—seated in a chair. It is a recent picture, surely taken within the last week or two.

We know that Donald was born on January 1 of this year, for there is a note to that effect on the back of the card, but neither the child’s real name nor the photographer’s is on the card. The photograph itself is little help. A penciled note across the bottom simply reads, “Maude Brown’s baby,” but no one recognizes that name. If the woman who left him does not return soon, one of our nurses will take the boy we call Donald Brown to an orphanage in Houston.

Well, my dearest, I must close now to get this letter in the post. Please write to me here at the hospital. I long to know that some place in this world is still whole, and that you and the boys are well.

Your loving and devoted husband,

Charles

Sunday, September 8, 1918

“GET ON WITH IT,” said a voice in Donald Brown’s head.

“Give me a minute!” he complained

to the empty room. He leaned against the iron bedstead, tilting his head back to feel the cool metal against his bare neck. He breathed out, cheeks puffed, and reached for the envelope.

Slowly, Donald worked two fingers under the loos

e bow that held the flap closed and let the ends of the ribbon fall away. Lifting the flap released the faint smell of age. With a thumb and forefinger, he pulled the letter and photograph slowly from the manila sleeve.

The doctor’s letter to his wife was on top. The testimony of a witness. No need to hear it again; Donald knew every word by heart. He held the fragile pages in his lap a moment longer, then set them aside. It was the photograph he needed, but dreaded, to see.

“Inhale

… hold … exhale … hold,” Mrs. Carhart would say. “Learn to calm yourself, dear boy. Control your breathing and relax. It is a skill that will help you through life.”

He closed his eyes and traced the edge of the card. His thumbs moved up the embossed border, left the roughness of the pasteboard mount and began gliding slowly over the print, which was smooth and cold as a marble headstone.

That’s enough, he thought.

Outside, Houston’s Fourth Ward was coming to life. A dray passed, still empty by the sound of it. The heavy wagon’s iron-clad wheels rattled over the brick street, o

ffset by the slow clomp of hooves. “Mornin’ Sam,” a neighbor called. “Mornin’ James,” the driver replied, but didn’t stop to talk.

Donald leaned on one elbow toward the shed’s only window, but even that slight movement disturbed a bit of lint from Naomi’s quilt. Distracted by the white specks tumbling through a beam of sunlight, he studied the particles for a few seconds, saw how quickly they slowed, then puffed to set them moving again.

Donald raised the photograph almost to the tip of his nose, and the blurry portrait grew crisp as the day it was made.

“You have a wonderful eye for detail,” Mrs. Carhart told him once, “but it is also your defense against things you do not wish to face.”

“Maybe so,” Donald said aloud. “Maybe so.”

He angled the print to catch more light. The sitter was a nine-month old boy—himself, Donald knew—propped in a chair. The child’s left hand rested on the arm of the chair, right hand in his lap, thumb and first finger just touching. Without thought, Donald’s hand did the same.

Through the spindles of the chair, he saw wallpaper and the corner of a shawl. Books leaned in soft focus against the back wall. The boy in the picture gazed not at the camera,

but toward a point slightly right of the lens. Below the image, a penciled note read, “Maude Brown’s baby.” On the back, a more deliberate scribe had printed in ink, “b. January 1, 1900.”

The simple contact print was well lit and properly exposed, any amateur could see that, but Donald saw details only a professional might notice: the quality of the light, the tonal range, the skillful depth of field. He looked up, peering over the top of the print and into the blurry corners of his room.

“Who are you smiling at?” he asked the child on the photograph. He ran his fingers over the penciled note at the bottom, “And please, who wrote these words?”

“Do you really want to know?”

“Stop it!” he said to the empty room.

“Inhale

… hold … exhale … hold,” the room replied.

He focused again on what he knew for sure. The card was not from a portrait studio. There were no trees or Greek columns painted on the background, and no grim-faced sitters, stiff and miserable thanks to the steel braces pressing at the backs of their heads.

“What about the pose?” said the voice in Donald’s head. “Babies don’t smile this way at strangers. That’s you. What did you see?”

“T

oo young to remember,” Donald whispered under his breath.

What he co

uld not see in the print, he saw in his mind: first the heavy wooden tripod, then the camera itself, bellows reaching for the child. He imagined the photographer, head and shoulders under the black cloth, composing the shot. He wanted to warn them both, “Leave now! Leave Galveston while you still can!”

Donald leaned forward, resting an elbow on one bent knee. He

squeezed closed his eyes and dropped his forehead in his hand.

Laughing

? Donald’s head popped up, instantly back in the present. He listened hard, but heard only chickens clucking in the yard. He slipped the photo and letter back into their sleeve, lowered the flap and retied the ribbon. He stretched the stiffness from his joints, then patted the table for his glasses. The base of the kerosene lamp felt cool. His fingers tapped across two books that Mrs. Carhart suggested he read. Reaching farther, Donald’s forearm swept left to right. His fingertips found a brass lens cap, then an empty film spool, which dropped from the table and rolled under the bed.

No glasses.

He turned toward the rough table that was both his writing desk and nightstand, but it was little help. He squinted at the objects just beyond his reach. A screwdriver, pliers and a small wrench were all lumps of equal volume. Three more pats, and Donald’s hands fell on the wire rims and thick lenses that were his windows to the larger world.

In one motion he sat up, pulled the glasses to his face, guided the steel loops behind his ears and twitched his nose to settle the heavy lenses in place. He paused to admire this simple, fluid action, one he’d practiced a dozen times a day since he was nine.

“My portholes

,” he called them, a joke shared only with himself.

Donald climbed from bed to retrieve the metal spool, then tucked it behind the curtain of his darkroom. Its walls and ceiling were black, the flatness broken only by

a handful of black and white prints pinned to the walls. A small red lantern sat in the middle of one shelf, a reminder to replace the candle.

Floorboards creaked under Donald’s bare feet. The shed was just large enough for his single bed, a workbench, a chair and of course, his da

rkroom. Above the workbench, a row of apple crates screwed to the wall overflowed with cameras and spare parts. One caught his eye. He took it from the shelf and laid his glasses aside.

“That should work!” he said aloud. Taking a Barlow knife from the

bench, Donald freshened the point on his pencil, allowing the shavings to fall into the pail that served as a trash bin. He licked the tip of the lead, opened his journal, laid it flat and began to draw.

“When ideas come to you, write them down at once,” Mrs. Carhart said when she gave him the odd little book with blank pages

.

He drew quickly

, jotting notes in the corners and linking them to his sketch with straight lines. Satisfied, he wrote the date:

Sunday, September 8, 1918, anniversary of the Great Storm

.

Donald closed the book, slipped it into his camera bag and lifted a pitcher to fill the baking pan he used for a sink. He splashed water on his face and had just reached for the fresh towel Naomi left for him each night when the screen door behind him swung wide. Clarence Stokes leaned in, one calloused hand gripping the edge of the screen, the other pressed flat on the outside of the shed.

“Good, you’re up! Saves me the bother of wakin’ you myself. Missus says breakfast will be on in ten minutes.”

“Thanks, Pa, just a second.” Donald patted the table for his glasses and slipped them smoothly over his ears, but the wooden slap-slap of the screen told him Clarence was already walking back toward the house. “Tell her I’ll be right in.”

“Come hungry, she’s fixin’ her Sunday feast,” Clarence called over his shoulder. “And hide that poster afore your ma sees it.”

Donald watched him go, suddenly sad for the gray in Pa’s hair and the limp that remained after his accident last year.

Poster? Donald forgot he’d left it on the chair by the door. He flattened it on the bed. A stern Uncle Sam with piercing eyes pointed a finger at Donald’s chest. “I want YOU for the U.S. Army,” the headline read. A recruiter had pressed it on him the day before, along with a registration form to complete.

I have until September 12

th

, Donald thought, four days more. What then? He rolled the draft registration form inside the poster, tied it with a scrap of twine and tucked the tube out of sight under his bed.

Donald hung his nightshirt on a nail and pulled clean BVDs from his drawer. He buttoned the fly of his denim pants, slid his arms into his shirt, stuffed the tail deep into his pants and rolled the sleeves neatly to his

elbows. He preferred a simple workman’s shirt to the button-on collars that made his neck itch. He wiped his cheek; a shave could wait.

Donald scanned the shed once m

ore. “You can sleep in his room,” Naomi and Clarence told him after their son left for the Army, but Donald preferred the roughness of the shed. Naomi kept it clean and a stealth tabby named Jones kept it free of mice. Compared to the dormitory bunks in the children’s home, this was luxury.

Donald pulled on fresh woolen socks, tugged at his boots and stamped each foot twice to plant the heels. H

is feet had grown over the summer, as had his shoulders and arms. He was already taller than Clarence. Naomi’s cooking had filled him out.

He dragged a brush across his thick brown hair and pat

ted a cowlick, but stopped when he caught his reflection in the window glass. Startled, Donald froze as if confronting a stranger on the street: Lean face. Strong jaw. Good teeth.

“Owl Eyes!” he said aloud.

The kids in school had called him that, and worse. He had to admit, they were right. The rims of the thick round lenses caught the light. They distorted his face, so that when anyone looked him in the eye, they saw the pinched sides of his head. The effect was comical: an owl with brown eyes ringed in white. He turned away in shame and disgust.

“Inhale

… hold …”

He

smelled bacon. Donald grabbed his flat leather cap from a nail by the door and stepped onto the boardwalk he’d built to keep from tracking mud into the house on rainy days.

He

thumped the outhouse door with his boot to check for snakes. A minute later he crossed the rest of the yard to be joined at the back porch by the Stokes’ yellow hound. Dropping to one knee, he tugged Bosco’s ears before opening the kitchen door.

“Morning

, Ma! What’s cooking?”

“You know perfectly well, young man,” Naomi said, wiping flour from her hands onto the sides of her apron. “Bacon, eggs, gravy and grits, and biscuits with butter and honey.” She stood on tiptoe to kiss him on the forehead. “Now wash your hands and pour yourself some coffee.”

Donald thought back to his time before the Stokes and couldn’t see

life without them. At ten he’d begun helping Clarence repair things around the old Washington Avenue orphanage, fetching tools and the like. Just months before the children’s home moved to its new address, Donald grew restless and the Stokes were glad to take him in.

“We’re going to miss you, Donny,” Naomi said, picking up a conversation they’d been having for a week. “You sure you need to join the Army?”

Donald stood in front of the icebox and sighed as he leaned back against its heavy wooden case.

“It’s

my time, Ma. The new law says eighteen-year-olds have to register, but that doesn’t mean I’m in. Anything could happen. They might not want me because of my eyes. They didn’t take Elton on account of his asthma. Besides, he says the war will be over in a few months.”

“Pshaw.

For three years now, smarter people than Elton Sparks have been saying the war will be over in a few months. I don’t mean to be uncharitable, but that man doesn’t know to come in out of the rain.”

“He may not be smart,

but he sure likes you.”

“He likes my apple pie, that’s what. He can smell one

clean from here to Sunday.”

Donald laughed. He loved to egg her

on. “Not just your apple pie.”

Naomi

turned from the stove, knowing his game.

“He loves your

cornbread, too.”

She wrinkled her nose and flipped a dish towel

as Donald pretended to duck. “It’s a wonder Elton made it all the way through high school,” she said, her attention back to the bacon cooking slowly in her largest iron skillet. “Is he still running errands for the reporters?”

“He’s been at the

Chronicle

since he took that job as a copy boy, but Jake Miller is teaching him photography. Elton’s trying hard. He bought a good camera, and a few months ago, Mr. Foley started giving him assignments.”

“Where does Elton

live now? He doesn’t have any kin nearby.”

“He’s been at Jake’s rent house since April. Jake wants me to move in, too.

If the Army doesn’t take me, Jake says I can live there and work at the newspaper.”

“As an errand boy?”