Masters of Death (29 page)

Hitler authorized the mass killings of the Holocaust, followed the murders in reports and photographs, and rewarded the perpetrators. Here he congratulates SS Reichsführer Himmler, “truehearted Heinrich,” on Himmler’s forty-third birthday, 7 October 1943.

In Poland in 1943 Himmler spoke openly to his generals and to the leaders of the Third Reich about “the extermination of the Jewish people . . . a glorious page in our history.” By then he was collecting books bound in human skin, and chairs and tables made from the bones of his victims.

SS mass killing descended directly to late-twentieth-century “ethnic cleansing” when Christian Serbs rationalized murdering Muslim Serbs as revenge for World War II repressions. Here, c. 1943, Himmler inspects Muslim Serbs in fezzes, the 23rd Bosnian and Croatian Waffen-SS “Kama” Division.

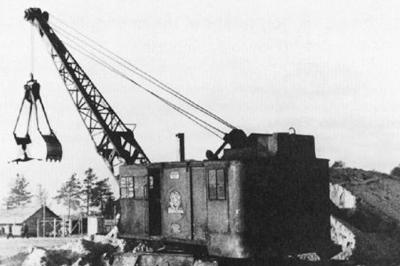

Assigned to exhume and burn the corpses of 1.5 million victims of Einsatzgruppen and Order Police mass killing, Paul Blobel resorted to power shovels and bone grinders and built massive funeral pyres, but still failed to eradicate the evidence of Nazi crimes.

After his capture by British forces in late May 1945 Himmler committed suicide by crushing a cyanide capsule he had hidden in his mouth. This previously unpublished photograph by British Army Major W. G. Thorpe was taken shortly after the former Reichsführer’s death. He was buried in an unmarked grave.

One set of Einsatzgruppen reports was discovered after the war; it supplied damning evidence for a U.S. military trial of Einsatzgruppen leaders at Nuremberg in 1947–48. Left to right, Ohlendorf, Heinz Jost, Erich Naumann and Erwin Schulz receive their indictments in the fall of 1947. Most of the mass killers in the Einsatzgruppen and the Order Police were never brought to trial.

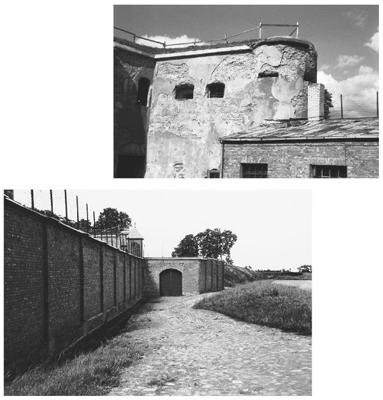

The Ninth Fort (right and below), outside Kaunas, Lithuania, stands today preserved as a memorial to its victims.

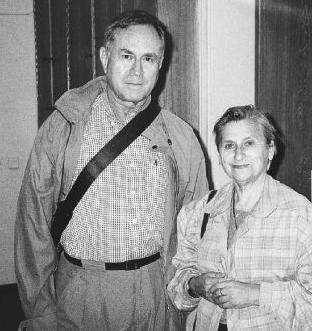

Fania Brancovskaja, shown here with the author at the State Museum of Vilnius Gaon Jews, escaped the Vilnius ghetto on the day in 1943 when all its remaining Jews were killed at Ponary. She and one of her sisters became anti-Nazi partisans fighting in the Lithuanian forests, the only two members of her extended family to survive the war.

Therefore “a conference on this matter was called on 18 September 1941 with the military administration. Since all previous warnings and special measures had been unsuccessful, it was decided to liquidate the Jews of Zhitomir completely and radically.”

The liquidation began as the Berdichev liquidation had begun: sixty Ukrainian militiamen surrounded and closed the Jewish district of Zhitomir during the night and at four in the morning broke down doors and drove families out of the houses and buildings where they had been crowded earlier in the month. Twelve trucks lent by the city and military administrations transported the victims to the massacre site, where a detachment of POWs had dug killing pits. The victims—a total of 5,145 men, women and children — were registered, robbed, disrobed and shot. “Fifty thousand to sixty thousand pounds of underwear, clothing, shoes, dishes, etc., that had been confiscated in the course of the action,” Blobel reported to Berlin, “were handed over to the officials of the NSV

29

in Zhitomir for distribution. Valuables and money were conveyed to

Sonderkommando

4a.”

At the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg in 1946, the Soviet chief counselor, L. N. Smirnov, offered into evidence a 1942 report by a German infantry officer, Major Rösler, who had commanded the 528th Infantry Regiment. Rösler had described to a superior a massacre he had witnessed in Zhitomir in the summer of 1941. He thought the massacre had occurred at the end of July, on the day his regiment arrived at the Zhitomir rest area. If so, then he may have seen the executions referred to in an Einsatzgruppen report dated 9 August 1941: “In Zhitomir about 400 Jews, mostly saboteurs and political functionaries, were liquidated during the last few days.” But Rösler specifies that the victims included women and children, which points to a later event. The infantry officer may in fact have observed the 19 September 1941 Zhitomir massacre and conflated it with the earlier liquidations; his description more closely matches Blobel’s ugly slaughter:

After I had moved with my staff into the staff quarters, on the afternoon of the day of our arrival, we heard rifle volleys nearby at regular intervals, followed a little later by pistol shots. I decided to find out what was happening and set off with my adjutant and orderly . . . in the direction of the rifle shots. We soon realized that a cruel spectacle was taking place; numerous soldiers and civilians were streaming toward the railway embankment behind which, as we were told, executions were being conducted. We were not able to see over the embankment, but at regular intervals we heard the sound of a whistle followed by a volley of about ten rifles, followed after awhile by pistol shots.

When we finally climbed up onto the embankment we were completely unprepared for the scene that confronted us. It was so abominable and cruel that we were utterly shattered and horrified. A pit about seven to eight meters long and perhaps four meters wide had been dug in the ground. The upturned earth was piled to one side of the pit. This earthen berm and the wall of the pit below were completely soaked in blood. The pit itself was filled with numerous corpses of all ages and sexes. There were so many corpses that it was not even possible to estimate the depth of the pit. Behind the berm stood a police detachment under the command of a police officer. The uniforms of the police bore traces of blood. In a wide circle around the pit stood scores and scores of soldiers from the units stationed in the area, some of them in bathing trunks, watching the proceedings. There were also a comparable number of civilians, including women and children. I approached the edge of the pit and saw something that to this day I have not been able to forget.

Among the bodies in the pit lay an old man with a white beard, his hand clutching a cane. He was panting for air, so it was obvious that he was still alive. I ordered one of the policemen to put him out of his misery. The policeman smarted back, “I’ve already plugged him seven times — he’ll kick off soon enough.”

The dead in the pit were not laid out in rows but were left where they happened to fall after being shot down from the ground above. All these people had been executed with rifle Genickschüssen and the survivors given coups de grace with pistol shots.