Masterpiece (30 page)

Authors: Elise Broach

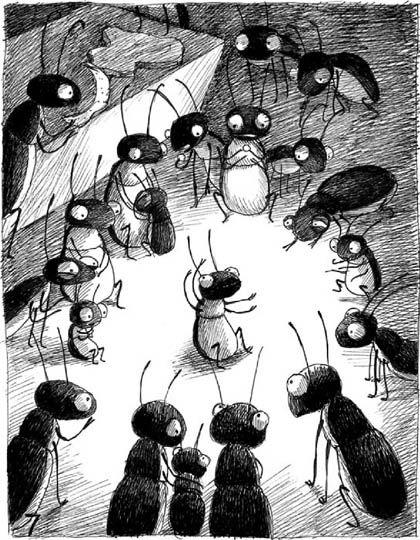

“Marvin!” Mama and Papa cried simultaneously, rushing over to him. They couldn’t stop hugging him, clearly overcome with guilt at having actually given permission for this last, most dangerous outing.

“My boy, we thought you were done for!” Uncle Albert boomed. “This business of leaving home to help the humans has gone entirely too far.”

“Indeed it has,” chimed in Marvin’s grandmother. “Have you learned nothing from the experiences of your

elders, dear boy? You must stop dabbling in human affairs! No good will come of it.”

Elaine’s eyes were huge. “Oh, Marvin, you don’t know how scared we’ve all been!” she cried. “Why, I just knew the most terrible thing had happened to you. When I heard you’d gone back to the museum again, I said, ‘He’ll end up drowned in that bottle of ink—’ ”

“Now, Elaine,” Aunt Edith interrupted.

Marvin thought of Elaine in the turtle tank and muttered under his breath, “You know what a good swimmer I am.”

But mostly he accepted their concerned scolding without complaint. He was beginning to understand that some of the most irritating things his family did stemmed from the depth of their love. And suddenly it felt wonderful to be worried about and fussed over, to be reclaimed by their messy closeness. Marvin remembered his lonely journey with

Fortitude

, when he thought that he might never see Mama and Papa and the relatives again. He realized that this was exactly what he had pined for—the thick web of affection that bound them all together. In some fundamental way, whatever terrible or wonderful thing happened to him always seemed to have happened to them, as well.

And so it was that Marvin was obliged to spend the evening telling all about his adventures, every exciting and horrifying detail: about the burglary, the dark trip through the city with

Fortitude

, the discovery of the three other

Virtue

drawings, the shocking revelation that Denny himself had masterminded the heists.

In between the myriad questions and discussions this prompted, Mama and Aunt Edith kept replenishing the table with platters of food—potato peelings, flakes of tuna fish, an orange rind, and crumbs of toast spread with a truly delicious rhubarb jelly—so that by midnight, everyone was well-stuffed and ready for a nap.

“You need to rest, Marvin,” Mama said decisively. “All this excitement is too much for you.”

“I am pretty tired,” Marvin admitted.

Elaine followed him into his room. “You’re so lucky,” she told him, careful to lower her voice so that the grown-ups wouldn’t hear.

Marvin nodded. “I know. I thought I might never be back here again.”

“I don’t mean that,” she said dismissively. “I mean lucky you got out of the apartment again. You’ve gotten to see the world!”

Marvin thought about that. He

had

seen the world. It had been scary at times, but also exhilarating. Who could have imagined it would be such a complicated, interesting place? Elaine was right—he was lucky. When you saw different parts of the world, you saw different parts of yourself. And when you stayed home, where it was safe, those parts of yourself also stayed hidden.

It wasn’t until late the next day that Marvin had a chance to visit James again. He made his way to James’s bedroom and found him hunched over his desk, drawing with his ink set. The pictures looked nothing like Marvin’s. The strokes were fat and unsteady. The things he drew had an abstract, disjointed look: an angular, foreshortened chair; the thick, pronged branches of the tree outside the window. James was concentrating so hard, he didn’t see Marvin crawl to the edge of the paper

and stand there, watching. When the boy finally noticed him, he gasped in delight and sheepishly set down his pen.

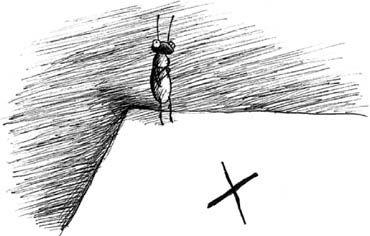

“Hey!” he said. “Little guy! I never know when you’re going to show up. We have to figure out a way to reach each other, you know? Like if I have a special message for you, maybe I can leave something in the cupboard so you know to come here. Or if you really need me, you can do the same thing.” He thought for a minute. “Something small . . . I know!”

He tore off a corner of the paper he was drawing on and made an ink X on it. “We’ll put this in the kitchen cupboard behind the wastebasket, right by your house. We’ll leave it facedown unless one of us needs the other, then we’ll turn it over. And if it’s turned over, we’ll meet here at my desk in the afternoon. Okay? Let’s say four o’clock, because I’m always home from school by then.”

James nodded emphatically, pleased with himself. Marvin smiled up at him. They might not be able to talk to each other, but there were so many other ways to say what they meant.

James pointed at his picture. “Look what I’m making. I’ll never be as good as you are . . . but I like it. It’s fun.” He lowered his finger and Marvin climbed onto it.

“And guess what. I have so much to tell you. I had to go to the police station! There was a jail and everything! And I talked to the FBI.” His face clouded momentarily. “I don’t think they believed me, exactly, when I said how

I found the drawings. But Christina kind of took over and told them about Denny, and then they let me come home.”

James leaned closer to Marvin, lowering his voice. “The FBI can’t find Denny anywhere. When they got to the apartment, he’d cleaned out all his stuff. He may have left the country! They think he went to Germany. Christina keeps calling his cell phone, and he doesn’t answer.” James sighed. “I know what he did was wrong and everything, but I still kind of hope he doesn’t get caught.”

Then he laughed suddenly. “But guess what. The drawings are all over the news. They’re not saying how they were found, but they’ve had all these experts look at them already, and it’s such a big deal. Everyone on TV is so excited. They had an interview with one of the German guys from that museum where the other two were stolen,

and he kept saying something like ‘Wunderbar! Wunderbar!’ My dad says that means ‘wonderful.’ ”

Marvin thought that it must be a dream come true for the museum people, to have all four of Dürer’s long-lost

Virtues

returned in one fell swoop.

James lifted Marvin close to his face, grinning at him. “And it’s all because of us! Well, you, mostly. But I helped. And Christina says they’ve gotten permission to put all of the drawings in some special exhibit, before they have to send them back. So they hung them this morning, and Dad just called and he says the lines for the museum are around the block. We’re going to go, all of us, this afternoon! Isn’t that great?”

James let out a long breath. “So you have to come, too, of course. You’re like a real, live hero!” He set Marvin down, looking at him proudly. “Nobody will ever know. But you are.”

That’s okay

, Marvin thought.

You know

.

As scary as it had been at times, the whole adventure had been something to share with James. It was a secret kept between them.

I

t was a strange little group that walked into the Met’s Drawings and Prints Gallery late that afternoon to see the newly reunited Dürer miniatures. Escorted by a museum guard, who had greeted them at a side entrance so that they could avoid the crowds, Karl, James (with Marvin tucked securely under his jacket cuff, having sworn to Mama and Papa that he wouldn’t budge from that position for the entire outing), and Mr. and Mrs. Pompaday, pushing William in his stroller, waited for Christina at the front of the exhibit.

Though she’d heard only the minimal details of the drawings’ recovery, Mrs. Pompaday could barely contain her pride over her son’s involvement—even in what she imagined was an ancillary fashion. She kept patting James’s back importantly and looking around for reporters.

“I wonder if anyone will interview you, James. They certainly ought to! Of course, once this business with the

museum is behind us, I expect you to get back to work on your own pictures. That’s where the real opportunity is. Four thousand from the Mortons! Just think what other people will pay for your extraordinary drawings.”

Mr. Pompaday harrumphed in agreement. “I’ve got a couple of partners at work who might be interested. Quite a way to build your college fund, James.”

Marvin winced, while James’s freckled cheeks turned a dark pink. “I don’t know if I’m going to keep drawing those little pictures,” he said. “They take a lot of time.”

“What do you mean?” his mother cried. “They’re marvelous! You can’t stop, James. Why, that’s your gift.”

“I know, but I was thinking I could do bigger drawings—”

“No, no, no,” his mother protested. “It’s their little size that makes them so delightful.”

Marvin inwardly groaned. How would he and James ever stop this charade? He couldn’t go on forging pictures. Just look at the trouble this had gotten them into already . . . even if it had led to the return of the stolen drawings.

Karl interrupted them. “Maybe he wants to take a break from it for a while. All artists need that occasionally.”

“Oh, I don’t think so—” Mrs. Pompaday began.

“My friends!” Christina cried happily, appearing in the doorway.

After the necessary introductions—“You have a remarkable son,” she told Mrs. Pompaday, who nodded

smugly—Christina led them through the crush of visitors to the third room, where the Dürer

Virtue

drawings were prominently displayed along one wall. Marvin clung to James’s wrist and peered up, trying to see them better.

Matted and framed, they were imposing despite their tiny size. Seeing them together somehow made you look at each drawing more closely, Marvin thought, instinctively comparing the four figures. Fortitude looked more determined and courageous, Justice both sterner and sadder alongside her sisters.

They were breathtaking.

Nobody can draw like Dürer

, Marvin thought,

not even me

. He suddenly and purely hoped that he wouldn’t have to copy any more drawings.

He was tired of it. He wanted to make something of his own.