Mary (14 page)

“Listen, Leb Lebovich”—Alfyorov swayed and grabbed him by the shoulder. “Right now I’m dead drunk, canned, tight as a drum. They made me drink, damn ’em—no, that’s not it—I wanted to tell you about the girl—”

“You need a good sleep, Aleksey Ivanovich.”

“There was a girl, I tell you. No, I’m not talking about my wife—my wife’s pure—but I’d been so many years without my wife. So not long ago—no, it was long ago—can’t remember when—girl took me up to her place. Foxy-looking little thing—such filth—and yet delicious. And now Mary’s

coming. D’you realize what it means? D’you realize or not? I’m drunk—can’t remember how to say perp—purple—perpendicular—and Mary’ll be here soon. Why did it all have to happen like this? Eh? I’m asking you! You, you damn Bolshevik! Can’t you tell me why?”

Ganin gently pushed away his hand. Head nodding, Alfyorov leaned forward over the table; his elbow slipped, rumpling the tablecloth and knocking over the glasses. The glasses, a saucer and the watch slid to the floor.

“Bed,” said Ganin and jerked him violently to his feet.

Alfyorov did not resist, but he was so unsteady that Ganin could hardly make him walk in the right direction.

Finding himself in his own room, he gave a broad, sleepy grin and collapsed slowly onto the bed. Suddenly horror crossed his face.

“Alarm clock—” he mumbled, sitting up. “Leb—over there, on the table, alarm clock—set it for half past seven.”

“All right,” said Ganin, and began moving the hand. He set it for ten o’clock, then changed his mind and set it for eleven.

When he looked at Alfyorov again the man was already sound asleep, flat on his back with one arm oddly thrown out.

This was how drunken tramps used to sleep in Russian villages. All day in the shimmering, sleepy heat tall laden carts had swayed past, scattering the country road with bits of hay—and the tramp had lurched noisily along, pestering girl vacationists, beating his resonant chest, proclaiming himself the son of a general and finally, slapping his peaked cap to the ground, he had lain down across the road, and had stayed there until a peasant climbed down from his hay wagon. The peasant had dragged him to the verge and driven on; and the tramp, turning his pale face aside, had lain like a corpse on the edge of the ditch while the great green bulks, swaying and sweet-smelling, had glided past, through the dappled shadows of the lime trees in bloom.

Putting the alarm clock noiselessly down on the table, Ganin stood for a long time looking at the sleeping man. Then jingling the money in his trouser pocket he turned and quietly went out.

In the dim little bathroom next to the kitchen, briquettes of coal were piled up under a piece of matting. The pane of the narrow window was broken, there were yellow streaks on the walls, the metal shower head curved, whiplike, out from the wall above the black, peeling bathtub. Ganin stripped naked and for several minutes stretched his arms and legs—strong, white, blue-veined. His muscles cracked and rippled. His chest breathed deeply and evenly. He turned on the tap of the shower and stood under the icy, fan-shaped stream, which produced a delicious contraction in his stomach.

Dressed again, tingling hotly all over, trying not to make any noise, he dragged his suitcases out into the hallway and looked at his watch. It was ten to six.

He threw hat and coat on top of the suitcases and slipped into Podtyagin’s room.

The dancers were asleep on the divan, leaning against each other. Klara and Lydia Nikolaevna were bending over the old man. His eyes were shut, and his face, the color of dried clay, was occasionally distorted by an expression of pain. It was almost light. The trains were rumbling sleepily through the house.

As Ganin approached the bed-head, Podtyagin opened his eyes. For a moment in the abyss into which he kept falling his heart had found some shaky support. There was so much that he wanted to say—that he would never see Paris now, still less his homeland, that his whole life had been stupid and fruitless, and that he didn’t know why he had lived, or why he was dying. Rolling his head to one side and glancing perplexedly at Ganin he muttered, “You see—without any passport.” Something like faint mirth twisted his lips. He screwed up his eyes again and once more the abyss sucked him down,

a wedge of pain drove itself into his heart—and to breathe air seemed to be unspeakable, unattainable bliss.

Ganin, gripping the edge of the bed with a strong white hand, looked in the old man’s face, and once again he remembered these flickering, shadowy doppelgängers, the casual Russian film extras, sold for ten marks apiece and still flitting, God knows where, across the white gleam of a screen. It occurred to him that Podtyagin nevertheless had bequeathed something, even if nothing more than the two pallid verses which had blossomed into such warm, undying life for him, Ganin, in the same way as a cheap perfume or the street signs in a familiar street become dear to us. For a moment he saw life in all the thrilling beauty of its despair and happiness, and everything became exalted and deeply mysterious—his own past, Podtyagin’s face bathed in pale light, the blurred reflection of the window frame on the blue wall and the two women in dark dresses standing motionless beside him.

Klara noticed with amazement that Ganin was smiling, and she could not understand it.

Smiling, he touched Podtyagin’s hand, which barely twitched as it lay on the sheet, straightened up and turned to Frau Dorn and Klara.

“I’m leaving now,” he whispered. “I don’t suppose we shall meet again. Give my regards to the dancers.”

“I’ll see you out,” said Klara as quietly, and added, “The dancers are asleep on the divan.”

And Ganin went out of the room. In the lobby he picked up his suitcases and threw his mackintosh over his shoulder, and Klara opened the door for him.

“Thank you very much,” he said, sidling out onto the landing. “Good luck.”

For a moment he stopped. Already the day before he had momentarily thought it would be a good idea to explain to Klara that he had never had any intention of stealing money

but had been looking at old photographs; yet now he could not remember what he had meant to say. So with a bow he set off unhurriedly down the staircase. Klara, holding the door handle, watched him go. He carried his suitcases like buckets and his heavy footfalls made a noise on the stairs like a slow heartbeat. Long after he had disappeared round the turn of the banisters she stood and listened to that steady, diminishing tap. Finally she shut the door, stood for a moment in the hallway. She repeated aloud, “The dancers are asleep on the divan,” and suddenly burst into soundless but violent sobs, running her index finger up and down the wall.

seventeen

The thick, heavy hands on the huge white clockface that projected sideways from a watchmaker’s sign showed twenty-four minutes to seven. In the faint blue of the sky that had still not warmed up after the night, only one small cloud had begun to turn pink, and there was an unearthly grace about its long, thin outline. The footsteps of those unfortunates who were up and about at this hour rang out with especial clarity in the deserted air and in the distance a fleshy pink light quivered on the tram tracks. A small cart, loaded with enormous bunches of violets half covered with a coarse striped cloth, moved slowly along close to the curb, the flower-seller helping a large red-haired dog to pull it. Its tongue hanging out, the dog was straining forward, exerting every one of its sinewy muscles devoted to man.

From the black branches of some trees, just beginning to sprout green, a flock of sparrows fluttered away with an airy rustle and settled on the narrow ledge of a high brick wall.

The shops were still asleep behind their iron grilles, the houses as yet sunlit only from above, but it would have been impossible to imagine that this was sunset and not early morning. Because the shadows lay the wrong way, unexpected combinations met the eye accustomed to evening shadows but unfamiliar with auroral ones.

Everything seemed askew, attenuated, metamorphosed as in a mirror. And just as the sun rose higher and the shadows dispersed to their usual places, so in that sober light the world of memories in which Ganin had dwelt became what it was in reality: the distant past.

He looked round and saw at the end of the street the sunlit corner of the house where he had been reliving his past and to which he would never return again. There was something beautifully mysterious about the departure from his life of a whole house.

As the sun rose higher and higher and the city grew lighter, in step with it, the street came to life and lost its strange shadowy charm. Ganin walked down the middle of the sidewalk, gently swinging his solidly packed bags, and thought how long it was since he had felt so fit, strong and ready to tackle anything. And the fact that he kept noticing everything with a fresh, loving eye—the carts driving to market, the slender, half-unfolded leaves and the many-colored posters which a man in an apron was sticking around a kiosk—this fact meant a secret turning point for him, an awakening.

He stopped in the little public garden near the station and sat on the same bench where such a short while ago he had remembered typhus, the country house, his presentiment of Mary. In an hour’s time she would be coming, her husband was sleeping the sleep of the dead and he, Ganin, was about to meet her.

For some reason he suddenly remembered how he had gone to say goodbye to Lyudmila, how he had walked out of her room.

Behind the public garden a house was being built; he could see the yellow wooden framework of beams—the skeleton of the roof, which in parts was already tiled.

Despite the early hour, work was already in progress. The figures of the workmen on the frame showed blue against the

morning sky. One was walking along the ridge-piece, as light and free as though he were about to fly away. The wooden frame shone like gold in the sun, while on it two workmen were passing tiles to a third man. They lay on their backs, one above the other in a straight line as if on a staircase. The lower man passed the red slab, like a large book, over his head; the man in the middle took the tile and with the same movement, leaning right back and stretching out his arms, passed it on up to the workman above. This lazy, regular process had a curiously calming effect; the yellow sheen of fresh timber was more alive than the most lifelike dream of the past. As Ganin looked up at the skeletal roof in the ethereal sky he realized with merciless clarity that his affair with Mary was ended forever. It had lasted no more than four days—four days which were perhaps the happiest days of his life. But now he had exhausted his memories, was sated by them, and the image of Mary, together with that of the old dying poet, now remained in the house of ghosts, which itself was already a memory.

Other than that image no Mary existed, nor could exist.

He waited for the moment when the express from the north slowly rolled across the iron bridge. It passed on and disappeared behind the façade of the station.

Then he picked up his suitcases, hailed a taxi and told the driver to go to a different station at the other end of the city. He chose a train leaving for southwestern Germany in half an hour, spent a quarter of his whole fortune on the ticket and thought with pleasurable excitement how he would cross the frontier without a single visa; and beyond it was France, Provence, and then—the sea.

As his train moved off he fell into a doze, his face buried in the folds of his mackintosh, hanging from a hook above the wooden seat.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

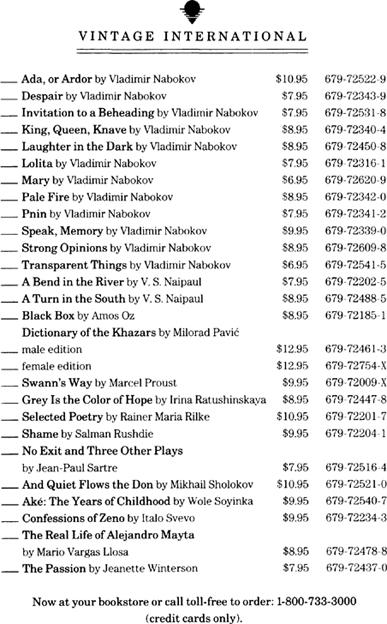

Vladimir Nabokov was born in St. Petersburg on April 23, 1899. His family fled to Germany in 1919, during the Bolshevik Revolution. Nabokov studied French and Russian literature at Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1919 to 1923, then lived in Berlin (1923–1937) and Paris (1937–1940), where he began writing, mainly in Russian, under the pseudonym Sirin. In 1940 he moved to the United States, where he pursued a brilliant literary career (as a poet, novelist, critic, and translator) while teaching literature at Wellesley College, Stanford, Cornell, and Harvard. The monumental success of his novel

Lolita

(1955) enabled him to give up teaching and devote himself fully to his writing. In 1961 he moved to Montreux, Switzerland, where he died in 1977. Recognized as one of this century’s master prose stylists in both Russian and English, he translated a number of his original English works—including

Lolita—

into Russian, and collaborated on English translations of his original Russian works.