Margaret Fuller (42 page)

Authors: Megan Marshall

So she kept on believing him—“I cannot do other than love and most deeply trust you.”

James Nathan had brought the “poor maiden” on board only to deliver her to her parents in England, he explained, to finish the good work he had begun. Margaret forced herself to sympathize with the “fair girl,” regretting that she had never met her, offering to ask Harriet Martineau’s help in finding the girl “friends and employment” if her parents didn’t welcome her home.

“She must suffer greatly to part from you,” Margaret wrote to James Nathan, “you who have been a friend to her such as it has been given few mortals to find

once

in this world and surely none could hope to find twice!”

Margaret felt much the same way. She had finally found a man “who combined force with tenderness and delicacy,” the same words of praise she had once ascribed to Sophia Peabody’s fiancé, Nathaniel Hawthorne. This was now a “certainty”: “Yes there

is

one who understands . . . and when we are separated and I can no longer tell [him] the impulse or the want of the moment, still I will not forget that there

has been

one.”

Margaret had been loved—desired.

In the days of the “beautiful summer when we might have been so happy together”—“happy in a way that neither of us ever will be with any other person”—Margaret wrote letter after letter to James Nathan, handing them to errand boys to deliver to ships waiting at the docks.

She put on her “prettiest dresses” to sit on

their

rocks at Turtle Bay, watching Josey sport in the water below.

One hot night she climbed down the boulders to bathe in the river, “the waters rippling up so gentle, the ships gliding full sailed and dreamy white over a silver sea, the crags above me with their dewey garlands, and the little path stealing away in shadow. Ah! it was almost

too

beautiful to bear and live.”

On nights like this Margaret “concentrated on our relation as never before.” “It seems to me not only peculiar but

original,

”

she wrote to James Nathan, feeling more certain that “indeed there

are

soul realities,” with “

mein liebster

” at a safe distance.

“I have never had one at all like it, and I do not read things in the poets or anywhere that more than glance at it.” She could feel James Nathan’s thoughts “growing in my mind . . . your stronger organization has at times almost transfused mine.” There had been “moments when our minds were blended in one,” and this “unison” beat “like a heart within me.”

She had given him Shelley to read, but there is “no poem like the poem we can make for ourselves”:

“is it not by living such relations that we bring a new religion, establishing nobler freedom for all?”

How hard Margaret worked to persuade herself—and James Nathan—of their disembodied “unison.” As she wrote in a

Tribune

essay that July, titled “Clairvoyance,” on the “wonderful powers” of the mind, “time and space” may yet be “annihilated” so that “lovers may be happy.”

In late July, Margaret finally received a packet of letters from James Nathan, only to learn that “the affair that has troubled you so long” had found no “definitive and peaceful issue”

—the “poor maiden” was yet to be settled elsewhere.

Worse, James Nathan appeared to have no thought of coming back to America. Margaret struggled to temper the language of her return letters. “

Now

is the crisis,” she informed him; he must “find a clear path” out of his entanglement.

She appreciated, at least, the “tender and elevated” tone of his letters, which allowed her to hope “we [may] ever keep pure and sweet the joys that have been given.”

Adopting Margaret’s own theory for the moment, James Nathan had assured her that “the precious certainty of spiritual connexion” was “worth great sacrifices,” and theirs would “bear the test of absence.” If she was indeed so much in his thoughts, Margaret responded, he must make note of the precise dates and times. Then they would compare notes and see whether there was a simultaneous “rush of our souls to meet . . . as used to be the case.” Yet, in retrospect, James Nathan’s sudden departure now seemed to her “sad and of evil omen.”

Margaret begged him to have his portrait taken for her as a keepsake, preferably “a good miniature on ivory”—“but do not have it taken at all unless it can be excellent.”

If he didn’t return, what would she do with Josey, who shook salt water all over Margaret’s pretty dresses and whose eyes seemed to be infected? The dog would need someone else to walk him. Margaret had not tramped in the woods since James Nathan left; she refused to climb the low wall that he had always lifted her across. Would he never return to take her in his arms again?

Rather than walk in the woods, Margaret had been visiting the new Female Refuge in the city, established by Rebecca Spring and other women of the Prison Association to help former prisoners find work after their release. “I like them better than most women I meet,” Margaret wrote darkly to James Nathan of the inmates. “They m[ake] no false pretensions, nor cling to shadows,” though she suspected they hid from her the “painful images that must haunt their lonely hours.”

When she wrote in her journal several months later that the year 1845 “has rent from me all I cherished, but . . . I have lived at last not only in rapture but in fact,” Margaret had in mind both her love for James Nathan and her encounters as journalist and volunteer with lives harder than her own.

Margaret had delayed her New England vacation, once planned for July, in order to receive her first letters from James Nathan as soon as they reached New York. But when only one “cold and scanty” missive followed the July packet in late August, she made arrangements to travel north to Cambridge and Concord in early fall. Waldo had made a short but satisfactory visit to Margaret in Turtle Bay in June while staying with his brother on Staten Island. That autumn at Concord, however, “our moods did not match.” Waldo was “with Plato”—preparing his lectures on “Representative Men”—Margaret wrote afterward to Anna Ward, and “I was with the instincts.”

Did she have Sam’s letter on Platonic affection still in mind?

Cary Sturgis was increasingly occupied with a new beau—William Aspinwall Tappan, a wealthy New Yorker who had caught Waldo’s fancy two years earlier. Waldo had published a poem by Tappan in one of the last issues of

The

Dial,

but mostly he enjoyed the young man’s company. Tappan spoke “seldom but easily & strongly,” Waldo approved, and he “moves like a deer.” Cary had taken an interest simply “because he is the greatest unknown to me now.”

She would marry Tappan in 1847 and move with him to Highwood, a country estate on property owned by Sam Ward in the Berkshires; they were still mysterious to each other, but the match satisfied Waldo, who had done everything he could to push them together, no longer able to tolerate the fascination Cary held for him at close range.

Over the summer, Henry Thoreau had built a small log cabin on land Waldo Emerson had recently purchased at Walden Pond to preserve the wooded acreage, and he had been living alone there since July. Ellen and Ellery Channing had moved into a new house on the outskirts of town at Punkatasset, leaving Ellen “very lonely and unhelped,” and Margaret worrying, “for she is to have another little one in Spring.”

Two-year-old Margaret Fuller Channing—Greta—would soon be joined by a sister, the infant Caroline Sturgis Channing.

The presence most palpable to Margaret that fall was Timothy Fuller’s. On the tenth anniversary of her father’s death, she wrote to James Nathan at “just about [the] time he left us and my hand closed his eyes.”

Sitting at her writing desk, Margaret stared at that hand, which since that day “has done so much”: edited a literary journal for which she had supplied more articles than anyone else, written two books and nearly one hundred newspaper pieces. Her writing hand seemed “almost a separate mind.”

“It is a pure hand thus far from evil,” Margaret was glad to say, and “it has given no false tokens of any kind,” unlike (she grew more certain of it by the day) James Nathan’s hand. “My father,” she asked, “from that home of higher life you now inhabit, does not your blessing still accompany the hand that hid the sad sights of this world from your eyes”?

A decade earlier, before his death, Margaret had suffered under Timothy’s stern authority, so accustomed to his failure to express his affection that—until the fortunate moment when she had been so ill, just before his sudden last sickness—she had burst into tears over the unexpected benediction. Perhaps this history with her living father, rather than Timothy’s premature death, was the source of the “childishness” that drove her to seek Platonic relations with men whose affection flickered just beyond her reach.

But now she wondered whether her father’s blessing did “still accompany” her. Margaret asked the question of “my friend” James Nathan—no longer

mein liebster.

She gave the answer herself: “I think it does. I think he thus far would bless his child.”

• VI •

EUROPE

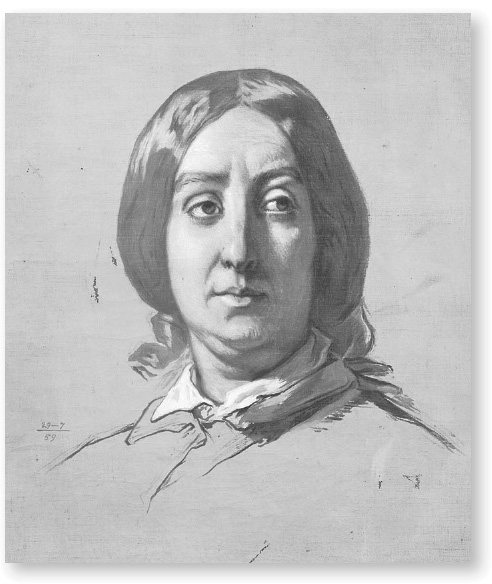

George Sand

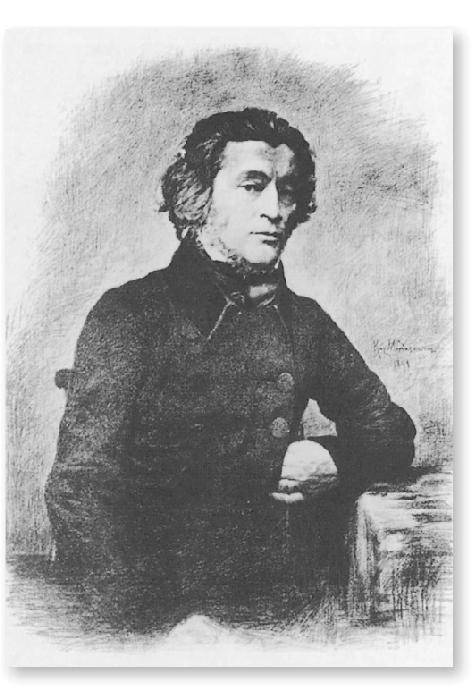

Adam Mickiewicz

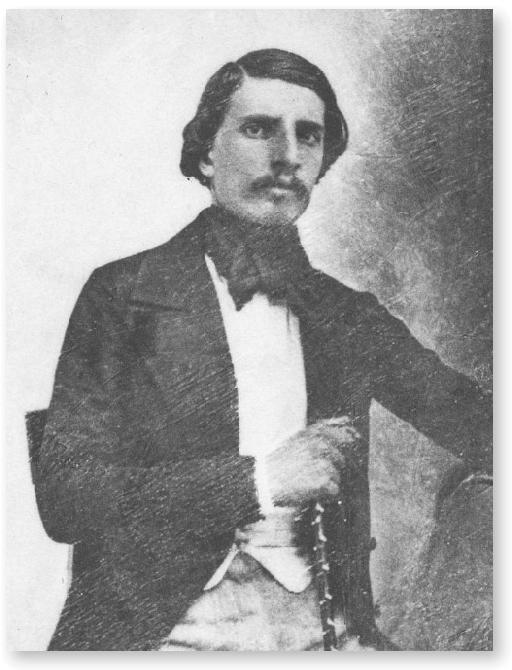

Giovanni Angelo Ossoli

17

Lost on Ben Lomond

W

HEREVER SHE WENT, HE FAILED TO APPEAR. THAT WAS

the troubling undercurrent of Margaret’s first weeks traveling abroad with her New York friend Rebecca Spring and her husband, Marcus, both reform-minded Quakers, and their nine-year-old son, Eddie, for whom Margaret served as tutor. (The Springs’ younger child, Jeanie, had been left behind with relatives.) Margaret could not have made the trip without accepting the generous terms of the governess position, which covered meals and lodging as well as her fare on the Cunard steamer

Cambria

in a record-setting Atlantic crossing of ten and a half days in early August 1846. Horace Greeley helped support the venture too, paying Margaret his highest rates and advancing her $120 on fifteen dispatches, which she initially titled breezily, “Things and Thoughts in Europe.” With no fanfare, she had become America’s first female foreign correspondent. Margaret continued to sign her columns with the distinctive yet anonymous star, intent simply on writing up the best material she could find and branding it with her own increasingly “radical” sensibility—a term she began to use as a badge of honor as she established bonds with Europe’s freethinking exiles and activists.