Many Lives (12 page)

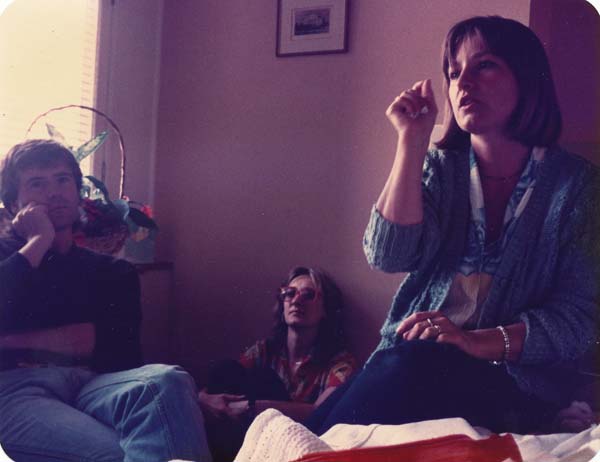

My sister Didi, supporting me

When I was filming

A Change of Place

in Budapest in 1994, I had it written into my contract that Didi would be accompanying me. When I was leaving, CBS, one of the television companies involved in producing the film, asked Didi if she'd stay on because they'd enjoyed her company so much. They even offered to pay her. âNo,' she told them, âbut I've had a lovely time, thank you.' Didi just does what needs to be done.

She and I both live in America. Didi saw me when I was first on the front cover of the listings magazine

TV Guide

when nobody in the UK did. I realized I wasn't as thrilled as I could have been and I wondered why. I realized it was because Mummy wouldn't be buying a copy. Didi was there to see it, though.

When you become well known you get fans, but you never know what your fans expect of you. When I was doing

An Ideal Husband

in 2001 at the Paper Mill Playhouse in New Jersey, a girl turned up at the stage door after a performance. I think I signed a photograph for her. She said she'd been longing to meet me and that she'd come all the way from Ohio. We chatted a bit and that was that. I finished the production, went back to Los Angeles and then, suddenly, she turned up in the condominium building in West Hollywood where I had an apartment and made friends with my daughter Phoebe.

I had to have a bit of a think about that. She invited Phoebe into her apartment. The walls were covered with photographs of me. âThis could be worrying,' I thought. Having an obsession like that made me think she was probably unhappy and had

problems in her life. Phoebe let her babysit Jude. I thought I'd better get to know her. I realized I had a decision to make. She had an image of me based on the fantasy characters she'd seen me play. I knew I was more than that and figured I probably had nothing to worry about. Anyway, I had nothing to hide. She seemed very bright and was obviously very efficient and organized. She knew everything about my career and remembered it all far better than I did.

I decided not to be anxious or swayed by fear. She wasn't in a happy state when we first met. She'd been through some terrible experiences in her life. I saw into her, I saw her need, not her adoration of a fantasy of me. I decided to hold on to what I saw with love, albeit at a distance. I could have been really worried; I could have reported her to the police. I could have said, âThere's a girl who has photographs of me all over the place, and it's really worrying me.'

That was ten years ago. Since then, I've seen Emily through the death of her mother, and through the death of her father. She looks after my house and my dogs while I'm away. She's my assistant when I'm in America.

When I started

Tenko

I'd been so very unhappy and those women gave me so much. We saw each other's needs and supported one another. That experience helped me recognize Emily's needs and I warmed to her. It's quite interesting what you can do once you've recognized whether it's love or fear that's guiding your decisions.

Being in the company of Maria Callas while I was playing at being her for the play

Master Class

for several months in 2010-11 was quite a challenge. She was a formidable woman. What David Beckham was to football, Maria Callas was to opera. Her peers were stunned by her ability; they really believed that she'd been touched by the gods, and that she radiated a divine energy in her voice. But she suffered terribly. She didn't have a happy childhood and, as an adult, was hit by one scandal after another.

Master Class

is set at the end of her career, and of her life. She died when she was 54.

When we took the play to Edinburgh we performed at the same theatre that she'd performed in 53 years before we were there. She'd been contracted by La Scala, the famed opera house in Milan, to do four performances of

La Sonnambula

. The management had then tacked on two more performances, which she'd refused to do. She was vocally exhausted and had to get back to Venice for a party arranged for her by Elsa Maxwell, the original celebrity gossip columnist. La Scala were furious. Ghiringhelli, who ran La Scala, sacked her.

When I did the play in Edinburgh, all sorts of weird things happened. During one performance I felt Maria Callas come on stage while I was at the point in the play where I am explaining to a student (beautifully played by Robyn North) how to approach playing

La Sonnambula

. Maria started gabbling in my ear in Greek, just as I was in the middle of a soliloquy. I wanted to slap her but there was nothing physical there to slap. It was terrible. It wasn't like she came and suddenly empowered me. She just gabbled in Greek, right into my ear. It was most

off-putting. Then I saw a curtain move up in the box known as the director's box. âThat's Ghiringhelli,' I thought. It wasn't ghostly. I was too busy to let it make me shiver. To top it all, I lost my voice. In 45 years I'd never lost my voice before. I could growl and I could squeak, but there was nothing in the middle. I had to miss the last two performances. I was distraught at letting everyone down, but in that wonderful old theatre, channelling that diva, it was strangely perfect.

Dying and Coming Back

Near Death

I was playing Aquilina opposite Ian McKellen's Pierre in Thomas Otway's

Venice Preserv'd

at the National Theatre in 1984. I'd come off stage and was removing my make-up because I had to get to the hospital. I'd promised I'd be there before 11 o'clock and had arranged to have a drink with the rest of the cast before going because we had a ten-day break from the show. I was rushing.

Suddenly, I was hit by a terrible premonition. A feeling of imminent catastrophe washed over me and the thought gripped me; âOh no, this is going to go really, really wrong.'

The play's director, Peter Gill, was already in the Green Room.

âI'm really not feeling good about this,' I told him.

âWell of course you're not,' he replied. âYou're going to hospital to have an operation.'

âI think it's more than that,' I said.

âAhhh, you'll be fine,' he tried to convince me.

âI won't be,' I thought.

Ian came in. âI'm not feeling good about this,' I told him.

âYou'll be

fine

, my dear.' He does that reassuring thing very naturally.

Well, whatever. âBye folks, see you in ten days' time.'

I put it out of my mind and got to the Royal Free. The nurse was cross. It was nearly 11 o'clock, I'd just come off stage and now I had to get into bed and pretend to be ill. I wasn't ill. I was just there for a necessary operation.

Everyone else on the ward was asleep. I think I managed to have a shower. The nurse showed me a mangy little bed in the corner. âEveryone's going to bump into it as they walk by,' I thought. It had a flimsy curtain round it. âNot nice digs.'

I was on the main ward: low rank, no privileges. No problem. I wasn't staying there long. I had ten days to have the operation and recover, then back to work.

The morning after surgery I painted my toenails, replaced my jewellery and started working on designs for our new house. By day three my temperature was spiking to 104 degrees and I was feeling very poorly. I was moved to a private room with en suite loo, an emergency button and a wonderful view of the whole of Hampstead Heath â special privileges. I was moving fast up the ranks. The problem was I was very ill.

The situation quickly unravelled. Having vomited green bile in a dramatic splash against the wall opposite the window, I turned to look at the clouds but I couldn't hold focus. I was fading, becoming part of the clouds. I was floating. No longer in pain, I was looking down on my body lying in a messy bed. I was floating on the ceiling of a white hospital room observing slippers on the

floor, books piled on the side locker and myself, lying blank-faced on the bed in a white nightdress.

There was a jump-cut to another scene. I don't know how it happened â it just did. I was being led down a wide, rough path towards a boulder; behind it was the most beautiful, warm and inviting golden light. I was being led by four Franciscan monks. I think that's what they were. They were to my left, wearing very coarse, brown, woven habits with hoods, as in images of St Francis of Assisi. Their hoods were up so I couldn't see their faces. Their habits were tied with thick rope belts and they wore sandals. Not of our time but also not frightening â not at all. Not even strange. The scene was welcoming. I knew the light was God and that the boulder was the stone of Jesus' tomb. I was aware that I was leaving

and

arriving; that I was going away from the pain and coming home. Suddenly two enormous eyes, like those of a huge owl, swooped in and filled my entire field of vision. I recognized them as my daughter Chloe's eyes, and they were saying, âOh, no, you don't!'

Chloe's eyes

Then, like a film going backwards, everything rewound and I found myself back in the hospital bed. I managed to press the emergency button, which remarkably was still in my hand, and set off the red lights and bells. A doctor rushed in and started fussing around. I said to her, âI think I just died.'

Without missing a beat she replied, âYes, I think you probably did.'

I was rushed into theatre for emergency surgery. They couldn't get hold of anyone in my family to sign me off, but Steph Cole came up and signed. Pretty ironic, really â in

Tenko

her character had suffocated mine with a pillow as a mercy killing at my character's request.

It was late on a Saturday night and a surgeon had to come from St Thomas' Hospital. He looked so dapper in his bow tie I made him breathe over me so I could check if he'd been drinking. Having come back, I didn't want to be killed off a second time.

I came round after the operation to a hazy consciousness, bandaged like a mummy and with tubes everywhere. I drifted for days; fed through a drip and filled with 12 different antibiotics to kill the infection that had nearly killed me.

In hospital

I was down to 90lb but, until my gut worked again, I was not allowed to eat anything. I had cheated one night with the pith of a cherry, and regretted it for hours afterwards â the pain was terrible. The next day they were going to operate and fit a colostomy bag. It would be permanent. They tried to reassure me that I'd be able to live with it but the thought was horrific.

Dear Ronnie Roberts saved me. She took over my room with her girlfriend Leigh and Martyn Stanbridge, my young companion at that time.

âThis is what we're going to do, sweet girl,' she told me. âWe're going to say a prayer and I'm just going to work on your tummy and I promise I won't hurt you.' Ronnie got me to imagine a tiny paralysed kitten, a little wounded creature, inside my belly. She had Leigh on one of my feet and Martyn on the other, gently manipulating the acupressure points that stimulate the intestines. Barely touching me she worked her healing magic, drawing light circles with the gentlest of touch on my stomach. During that night I passed wind. Everything had joined up again and I didn't have to have a colostomy.

Aiding my recovery. Left to right: Martyn, Leigh and Ronnie

Ronnie is so spiritual and also so practical. Isn't that the way it's meant to be? The practical and the spiritual are not mutually exclusive. You can turn washing-up into a spiritual task. You can fold the clothes, definitely bathe a baby and you can help a friend, with practical spirituality.

John came to visit me when I was still very poorly. I was also a filthy mess. He asked me if I needed anything.

âYes! I need a bath. I need to wash my hair. Look, it's got bile in it. The most the nurse will do is pat me with a wet flannel.'

He gathered my wraith-like body in his arms and carried me to the bathroom, somehow wheeling the drip stand I was connected to alongside us. He stripped me bare, covering the bandages wrapped around my stomach with a nurse's apron, and proceeded to wash my hair and bathe me in the shower. I was like a limp rag doll in his hands. He washed me gently, until I was clean. There was only one person I knew who would have done such a mad thing. That was John.

My agent Maureen came to see me with a thick stack of scripts. âThis is what we've been waiting for' she said, and plonked them on the bed.

âOh, Maureen that's too heavy, I can't take any weight on the sheet.'

She put them on the side table.

âRead through them when you can,' she said on her way out.

I couldn't show any interest. Work seemed a long way away. I was weak and felt barely alive. Later, I needed a tissue. Maureen had put the scripts on top of my box of tissues. To get to the box I had to move the pile, and I only had the strength to lift one script at a time. I lifted the first one and it was so much effort I thought, âNow I've got it in my hand I might as well read it.' Once I'd started, I couldn't stop. I read the whole night. I read through the entire series of 13 episodes. It was brilliant, it was mine, and I had to do it.

The script was for a television series called

Connie

. It was about a woman returning to the UK to take back control of her family's ailing business after living in Greece. Connie was a grafter. She was a survivor. She was a trickster. I liked her immediately. I knew her character could mend me. I knew I could use her to obliterate the sadness from my life once and for all. By entering the world of this formidable and courageous woman I could bring about my own recovery.

The trouble was I had to get the part. I phoned Alan Dosser, the director, and said, âShe's mine.' He asked for a meeting and I lied that I was down at my parents' house in Somerset, had not been very well and didn't want to come to London, hoping we could just do it on the phone.

âThat's fine,' he said, âI'm coming to the West Country next week.' So I discharged myself from the Royal Free, promising my doctors I would arrange to continue the intravenous antibiotics by daily injections, which turned out to be like being injected with an icing syringe.

A friend arranged a private ambulance and I beat Alan to the West Country by a couple of days.

My mother offered me her complete backing. âDarling, I can't believe how determined you are to recover,' she told me. âWhatever you decide to do, I will support you, totally.' She couldn't believe I'd survived. She'd probably been thinking I'd die and she'd have to bring up Phoebe and Chloe.

Martyn and Mummy arranged me in a deck chair outside the beach hut. Once I was sitting, that was it. I couldn't move. I was so ill. I still wasn't much more than a wraith, so Mummy put padding in my bra. I couldn't let Alan see what kind of state I was in. Martyn had to take care of the tea. I told him just to offer and to be aware of everything without making me boss him about. I had it all very carefully stage-managed. Alan was an anarchist, a risk-taker. He's wickedly good news. He'd been artistic director at the Liverpool Everyman and was used to sailing close to the edge. Still, there was no way I wanted him to know the state I was in.

The meeting was going very well and the conversation was flowing. Then I got rather excited about something Alan was saying. I forgot myself momentarily and thought I'd stretch my legs on the white picket fence in front of me. I lifted one leg and put it on the fence. It took all my energy. I couldn't lift my other leg to join it, and remained in that ungainly position for the rest of the meeting.

Connie: another life, another chance, another beginning. She was going to bring me back to being, anew.

It was the middle of the second day's rehearsal. I was still weak.

âAlan,' I said, out of everyone else's earshot. âYou know, I don't think I'm going to be able to do this.'

âI understand â that's OK,' he replied. Without missing a beat, he continued, âDo you want to stop now, or do you want to carry on blocking out the scenes so we've got it blocked for anyone who might take over till the end of the day?'

I told him I'd keep going and at the end of the day he said, âSee you tomorrow.' It was just a little moment.