Making Ideas Happen (7 page)

Read Making Ideas Happen Online

Authors: Scott Belsky

Take a moment to consider two “projects” in your life right now: a personal project related to your family or home, and a work project. Think about the current Action Steps for each of these projects—the stuff that you need to do. Are these Action Steps dispersed throughout messages sitting in your e-mail in-box? A notebook or journal?

Sketched on a napkin?

Do you have any Backburner Items for these projects? What about References? Are they stacked around your office, or tucked away in files where you’l never find them?

Here are a few things to keep in mind:

Actions Steps should be managed separate from e-mail.

Have you ever found yourself rereading e-mails repeatedly, trying to distil the Action Steps when the time comes to actual y do them? E-mail can kil productivity because the actionable information you receive is always clouded by Reference material. Your Action Steps become hidden within the e-mails and then gradual y buried by other e-mails. For this reason, Action Steps should have a space (or system) of their own. We wil discuss how to pair e-mail with a system for managing Action Steps in the section ahead.

When it comes to taking action, work and personal life collide (and that’s

okay).

People tend to separate the actions they must take in their personal lives from those in their professional lives. While formal “to-do” lists and applications empower you at work, Post-it notes on your refrigerator keep you on task at home. But observing the most productive people reveals that Action Steps are Action Steps, regardless of their context. Priorities may change, but managing everything actionable in one system is your best bet. New online task management tools with mobile versions help make your life’s Action Steps accessible to you wherever you are. By using the same system, you are able to prioritize (and complete) Action Steps whenever (and wherever) you want.

You wil also find that you and your team are more likely to complete work-related Action Steps when they are intermingled with personal Action Steps.

Actions are truly “delegated” only when they are accepted.

While many project management methods support “to-do” lists that multiple people can share, true accountability is never achieved unless your team members choose to accept their delegated Action Steps. Not only should outstanding work tasks be transparent to al members of the team (or at least one or two other col eagues), but your col eagues should actively accept or reject Action Steps that you assign them. This conceptual “handshake” creates accountability and eliminates the ambiguous Action Steps that notoriously clog the progress in any project.

Teams that exchange Action Steps via e-mail can agree that some form of acceptance or confirmation is required. When a col eague sends you an Action Step that is unclear or incorrect, you should reject it and seek more clarification. Doing so wil prevent the Action Step from lingering in the realm of ambiguity. For teams that use paper lists or wal charts, a best practice is to have al members write up their own Action Steps (in their own handwriting)—even those that are delegated to them. Doing so implies understanding and acceptance. Regardless of your method for managing Action Steps, it is vital that you (and your project partners) never accept an Action Step unless it is clear and able to be executed.

Sequential tasking is better than multitasking.

It is impossible to complete two Action Steps at once, which would suggest that “multitasking” is a myth. However, you can easily focus on more than one project at once if the Action Steps in al of your projects are defined and organized. You should aim to jump quickly between projects with as little unproductive downtime as possible. The secret is ful y breaking down the elements of each project.

Capture and Make Time for Processing

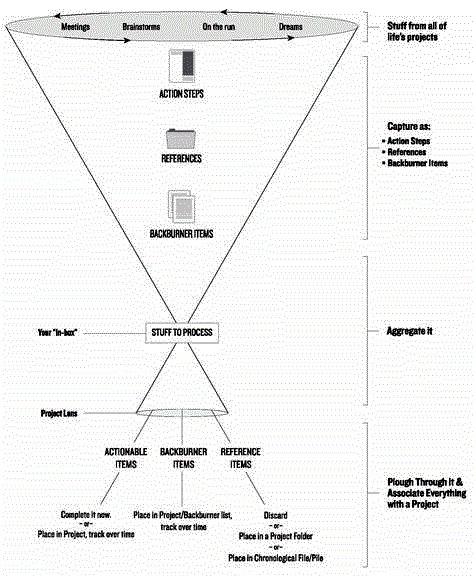

As you move through your day of meetings, brainstorms, and other occasions of creativity, you wil start to accumulate Action Steps, References, and Backburner Items.

Handouts, random pages of notes, e-mails, and social network messages wil build up al around you. Often these items wil get buried in notebooks, pockets, online in-boxes, and computer files almost as soon as they are created or received.

Ideal y, in your written notes you wil have kept your Action Steps separate from everything else. However, you wil stil need time for processing—going through al of your day’s notes and communications and distil ing them down to the primary elements.

For those who stil take paper notes and appreciate tangible project management, you wil want to use a tangible in-box—a general pile of stuff that has yet to be classified.

Most productivity frameworks—like David Al en’s

Getting Things Done

—suggest such a central clearing-house for al of the stuff that you accumulate but can’t immediately execute or file. This in-box is not a final destination, but rather a transit terminal where items await processing. During a busy day of meetings, you wil not have time to start taking action or filing things away.

How about al of the digital stuff that flows in every day? Your e-mail in-box is the primary landing spot, but information also flows into other online applications. While your tangible in-box, sitting on your desk, is singular, the digital equivalent is becoming more of a col ective. Ideal y, you should set your settings in social networks to forward messages to your e-mail in-box for the sake of aggregation. When you commit time for processing, you’l want to limit the number of places you need to visit. If you can’t aggregate the flow of e-mails and other digital communications in the same place, then you need to define the various pieces of your col ective digital in-box. For example, my col ective digital in-box includes my e-mail program (which receives messages from al other networks), a Twitter aggregator, and the in-box in my task management application (where I accept/reject stuff sent from my col eagues who use the same application—and then manage this information by project). When the time comes for processing, these are the three digital places I need to visit, along with the tangible in-box ful of papers on my desk.

As you can see, the “in-box” of the twenty-first century varies for everyone. You must concretely define your col ective in-box before you start processing. Peace of mind and productivity starts when you know where everything is. The combined in-box says, “Don’t worry, al of your stuff (and the Action Steps, Backburner Items, and References contained within) are in a defined place, waiting for you and ready to be sorted.”

If you live a digital lifestyle, your ability to process your in-box may be at particular risk without some sense of discipline. The reason: in the era of mobile devices and constant connectivity, it has become al too easy for others to send us messages. As such, our ability to control our focus is often crippled by the never-ending flow of incoming phone cal s, e-mails, text messages, and in-person interruptions—not to mention messages from other online services. Thus it is important that you avoid the trap of what I have come to cal “reactionary work flow.”

The state of reactionary work flow occurs when you get stuck simply reacting to whatever flows into the top of an in-box. Instead of focusing on what is most important and actionable, you spend too much time just trying to stay afloat. Reactionary work flow prevents you from being more proactive with your energy. The act of processing requires discipline and imposing some blockades around your focus. For this reason, many leaders perform their processing at night or at a time when the flow dies down.

Time spent processing is arguably the most valuable and productive time of your day.

While processing, you wil sort everything and distinguish Action Steps, Backburner Items, and References. With Action Steps, you wil decide what can be done quickly and what must be tracked over time by project—and possibly delegated. With other materials, you wil make judgments about what can be thrown away and what must be filed.

As you start to tackle your col ective in-box, you wil realize that any in-box, on its own, is a pretty bad action management tool. It is difficult to keep your Action Steps separate from References and other noise. The constant stream of e-mail certainly doesn’t help. In addition to e-mail, you may also receive other types of incoming communications in the form of Tweets, Facebook messages,

etc.

Some are actionable, or contain actionable elements, while others are simply for reference (or for fun).

Given the unyielding flow of communications, you wil want to capture and manage your Action Steps separately. Despite the many tricks involving “action subfolders” and other ways to manage and prioritize Action Steps within an e-mail system, there is nothing better than giving Action Steps their own sacred space to be managed by project. The Action Method suggests that Action Steps should be managed separately from communications. The solution can be as simple as a spreadsheet or to-do list where al Action Steps are tracked (and can be sorted by project name or due date). You can also make use of more advanced project management applications that manage Action Steps and support delegation and col aboration. What you want to avoid is a mishmash of actionable items amidst hundreds of verbose e-mails and other messages scattered in various places.

For teams that manage Action Steps via e-mail, actionable e-mails should have “Action” as the first word in the subject line. For Reference e-mails, you should start the e-mail’s subject line with “FYI.” By establishing a common language with your col eagues, everyone wil be able to sort their e-mail in-box and view Action Steps using these keywords.

Feel the flow of the Action Method.

Every new day generates more ideas, notes, and communications that flow into your col ective in-box. At periods of the day that you designate for processing, you break everything down into Action Steps, Backburner Items, and References. You associate each item with a project, whether it is personal or work-related. As you are doing this, quick actions are being completed while longer-term Action Steps are being added to the appropriate project’s task list or your task management application—with a project name (and due date if necessary). Backburner Items are added to the appropriate folder or list. And Reference materials are either being discarded or stored by project or perhaps in a chronological file.

Feel the flow, from creativity to capturing the elements, processing them, and

then managing them by project.

Capture!

Capture Action Steps relentlessly. During a brainstorm or a meeting, or on the run, you wil generate ideas, and those ideas wil disappear unless they are broken down into concrete verb-driven Action Steps. Col ect them using whatever notebook or technology option you desire—but try to keep Action Steps separate so they stand out amidst your References and Backburner Items. Some people e-mail themselves throughout the day, while others capture tasks on a mobile device that automatical y syncs with an online task management tool. Whatever method you choose, it is critical that your Action Steps stand out and can be managed separately from al of the other stuff.

If you find yourself with extraneous scraps of paper or unfiled e-mails containing Action Steps, Backburner Items, and References, place them in your in-box for processing.

Identify your collective in-box.

In addition to your physical in-box, you also have your e-mail in-box among other digital sources of information. Identify and then consolidate the number of digital in-boxes that you need to manage.

Process!

Take a few hours each day (or a minimum of a few nights per week) to process the contents of your in-box. As you review the pile (or list of e-mails), discern what is actionable and what is not.

• If actionable, identify the Action Steps. For Action Steps that can be accomplished quickly (like make a short phone cal or pay a bil ), do them right away. David Al en cal s this the “two-minute rule”—if it can be done in under two minutes, it should be done right away. After al , it wil take a minute or so just to enter it into your system, so why not just take care of it already?

• Whatever action management system you use, Action Steps should be recorded in a consistent way, assigned to a project, and given a due date (when applicable). By doing this, you are setting yourself up for ultimate productivity.

• Place Backburner Items in your Backburner folder, labeled with the appropriate project name.

• Try to discard as many References as you can, because most handouts and notes wil ultimately never be used. For those References that must be stored, file them away by project or use the chronological pile approach.

PRIORITIZATION:

Managing Your Energy Across Life’s Projects

DYNAMIC CREATIVE PROJECTS—

as wel as cumbersome logistical projects —become more manageable when they are broken down into elements. Once we are able to approach our work (and life) as a series of Action Steps, Backburner Items, and References, we wil have to decide where to start. We must prioritize because we can only focus on one Action Step at a time. Prioritization should help us maintain both incremental progress as wel as momentum for our long-term objectives. Prioritization is a force that relies on sound judgment, self-discipline, and some helpful pressure from others.