Magic Banquet (11 page)

Authors: A.E. Marling

Tags: #dragons, #food, #disability, #diversity, #people of color

It was a shame. Aja liked most of the

guests. Some had almost been kind to her. They could’ve become

friends, maybe even family. Leaving would mean never seeing another

course, or the next pattern in the carpet. But, no, she wasn’t

meant to stay. She didn’t belong.

Aja hobbled the rest of the way to the

doors, and she had to lean against them, fighting for air. Why did

her breathing rasp so? Exhaustion crushed her.

Something was wrong.

Straining against the door made her arms

feel as if they would break. Gold leaf designs in the wood showed

people with goat legs dancing and pouring wine over each other. She

could not budge the door.

“Let me out!”

Aja looked for a lock, a bolt, a handle. Her

vision blurred, as if from tears, but her eyes stung with

dryness.

“I didn’t drink the pomegranate elixir. You

must let me out.”

A heat flew overhead, and the djinn parted

the doors. They opened into the warehouse’s blackness.

“You may leave,” the djinn said, “but you

may not return.”

Aja took an unsteady step into the

portal.

“And you’ll stay as you are until your spark

dies.”

Something in the djinn’s voice stopped Aja.

It had sounded like a note of pity. Aja asked, “What do you

mean?”

The djinn waved a hand in a fan of

brightness. The air rippled as if in a mirage, and it bent into a

disk of glass. Within it, Aja saw the lamp-lit ballroom, the table

and guests in the distance. It was a mirror. In the foreground

slouched an old woman. A hag, a wrinkled creature, she resembled a

dried-out lizard in a white robe. She looked close to her last

breath. Aja was certain they had never met, but something about

that ancient face was hauntingly familiar.

The hag wore a bracelet of green glaze. Aja

wore the same kind of jewelry, exactly the same.

Her heart pattered, frantic and faint. She

pointed a trembling finger at the crone in the glass. The crone

pointed back.

Aja’s voice croaked. “Who is she?”

“You ate the ‘Fruit of Maturity entire,” the

djinn said. “Had you been any older, it would’ve aged you to

death.”

Aja ran a hand over her face. So rough, like

ruined leather. She groped for a strand of her hair, brought it

before her eyes. She couldn’t focus on something so near, but she

glimpsed its whiteness.

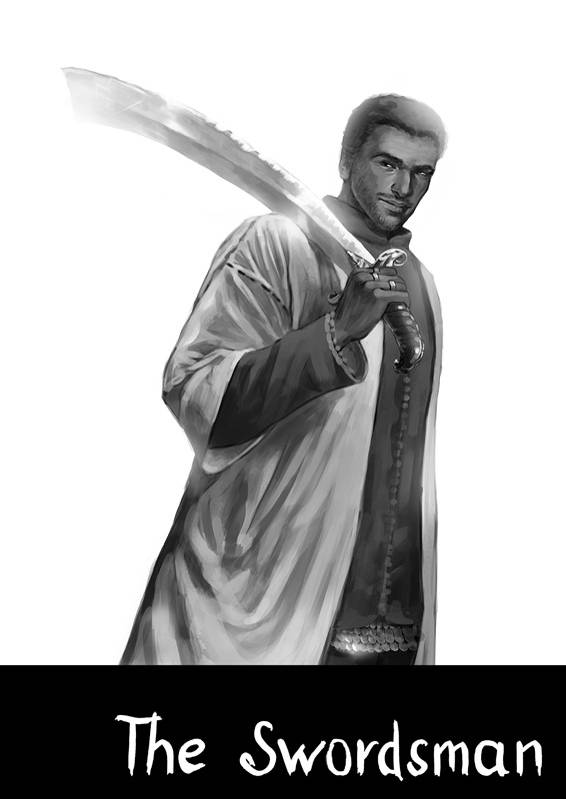

Side Dish:

THE SWORDSMAN’S TALE

If he grew up in the City of Gold, then I

did in the City of Diamonds. My grandfather was the finest gem

carver in the lands. My father, not so much. Me, not at all. Look

at these rough-wrecker hands of mine. Couldn’t carve limestone

boulders. Not that I’m complaining. Had plenty enough growing

up.

How I loved playing hot brick with my

sister. We’d run through the Bazaar of Fallen Stars. We’d hide in

the branch caverns of the banyan trees. She’d tell me to run up the

side of a ziggurat, and I would. Oh, a ziggurat is like a pyramid

with steps. I mean levels. It has steps you can walk up, too, or

maybe it’s less walking than climbing and gasping.

At the top of the ziggurat, the priest read

the future in the webs of the sacred spiders. Me, I only could see

a messy white tangle of silk, that and a songbird caught and

hanging dead. Sad, I know. The priest, though, he could see my

fate. This was what he told me when I was six years old.

“

Fosapam Chandur’s fate is bright,

His parents will be proud,

That he’ll finish his fights,

Gain or loss, he will be unbowed,

He will marry a young woman,

Eyes a’glitter, mind keen,

She will bear a strong son,

The greatest family yet seen.

Count his wealth in more than jewels,

Measure him, if you dare,

He’ll better countless fools,

And lions will run from his roar.”

Sixth Course:

SALMON OF KNOWLEDGE, ROASTED

SERVED WITH WATER OF OBLIVION

The guests looked on Aja with sorrow. Janny

saw her, twitched away, and then groaned, clutching her back. Pain

also throbbed in Aja’s spine. Now she was old, and Old Janny was

young.

Aja collapsed on a pillow and felt a knife

driving into her rear.

Ahh!

But there was no blade, only her

own bones digging into her skin. She added a second cushion.

The Banquet’s power had almost killed Aja,

and it could also cure her. She would need it to. The only other

way was to leave and accept death from unnatural old age. That, Aja

wouldn’t do.

She had chosen a seat next to the swordsman.

He could possibly give her a slice of his orange. Even if it didn’t

make her young again, she hoped it would help her breathe

better.

The swordsman glanced at her once, then

never again. He said something that she could not hear.

“What?” Aja held a hand to her ear.

“Your fruit, what was it supposed to

do?”

“Maturity,” she said.

“Guess not the kind you wanted.” He cradled

the empress’s head in his arm, squeezing another drop of orange

into her mouth.

A splintery zing shivered its way through

Aja. Could someone have ever cared for her that much? Death would

come before she found out, unless she reversed her aging. The Apple

of Youth was gone, eaten to the core, but the stewed phoenix could

replenish life as soon as it was served. On her trudging walk back

to the carpet she had asked the djinn if the phoenix was the last

course.

“No, the last is dessert.”

“Then, second to last?”

The djinn had offered no more. She had left

Aja to wonder how many more courses she would have to survive. Aja

struggled just to fit enough air into her lungs.

A mouthful of health was what she needed.

How to ask the swordsman for a piece of his orange? Aja fidgeted

with her brass bracelet, then spoke to him.

“You were wise. All that power on the table,

and you picked the fruit that’d save everyone else.”

“I’m not wise,” he said. “I just think what

the best of the royal guards would do in my place. Then I do

that.”

“That has the smell of wisdom,” Aja said. If

only she had known someone on the streets as dependable as him. The

swordsman would’ve made the best brother.

He tucked a lock of damp hair into the

empress’s shawl. “She trusts me too much.”

Aja considered if it was wrong to think of

herself, to ask for any help, to hope for better.

Who am I? An

old lady who’d never even been kissed.

The thought rotted inside her.

She didn’t even look up at the nearing

clomp-clomp sound of the Chef’s feet. Her stomach weighed her down

in a stony block. She wasn’t hungry, and she would eat nothing

until the stewed phoenix arrived.

“Food is culture.” The Chef’s voice flowed

like spiced oil. “The only way to know a culture is to eat it. To

understand the significance of each dish, its heritage, its

traditions.”

Below his massive boots, the carpet

displayed sheep grazing on a cliff bluff overlooking the sea.

Silver threads wormed around each other, and a cavern opened

beneath the rug pasture. Aja leaned forward, but that didn’t help

her aged eyes see any clearer. A river ran through the design of

the underworld, a lone boat crossing to a fearsome gate. Was that a

three-headed creature beside the yawning doors?

“To mix dishes from two cultures risks

chaos,” the Chef said, “but I do so for the perfect compliment of

entrée and drink. This salmon was roasted on a grill of flaming

swords. Seasoned with thyme and honey, enlivened with vinegar and

orange zest.”

The swordsman’s belly growled like a caged

lion.

“Think of something you want to know,” the

Chef said. “Take a bite. You’ll gain all the knowledge you desire

and more.”

Against one arm, the Chef supported a

chopping block. Pink flesh of a fish glistened. Sprigs of herbs

garnished it. He motioned with a knife to the djinn, and she

carried forward a black vase. Ghostly figures painted on it knelt

by a riverbank.

“If the salmon’s knowledge is not to your

taste, or if you have any memory you want washed away, drink,” the

Chef said. “This amphora holds water of unmindfulness. Drawn from

an underworld river, where souls forget their past lives.”

He held the knife handle first to the lord.

The blade was a spike of bronze resting against the Chef’s arm.

“Lord Tethiel, what would you learn?”

“I’m of an age where new knowledge tastes

stale.” He waved away the fish board.

How could the lord refuse another course?

Aja shook her head, and her neck clicked. An aching stomach she had

learned to live with, but this was a hunger of the mind. Night

after night she had lain awake, wondering who her mother was. Had

she died? Or had Aja walked by her in the market without

recognizing her? Her mother may have even been a queen who had lost

her princess daughter through a tragedy.

Her father, Aja remembered him well enough.

He had smelled of onions, coughed with a deep grunt like a warthog,

and tickled her with a forest of a beard. His arms had enclosed her

with such warmth she had felt snug, complete, safe. Aja couldn’t

bring to mind his face. That she regretted. Of her mother she knew

nothing.

No harm would come to her from one bite of

salmon. She didn’t see it as truly eating. Just a taste.

The lord glanced at her, and she puffed

stray hair out of her mouth. She had been chewing on it. A few of

the strands had fallen out. The lord spoke with a voice pitched to

all the guests. “You are right to fear. The problem with learning

is that you begin to understand how little you know.”

The Chef offered the salmon to another

guest. “This fish satisfies with complete knowledge of a

subject.”

The lord nodded to the amphora. “And with

forgetfulness so close at hand there seems little risk. Any fool

can learn, but forgetting, that’s a rare skill.”

Aja asked, “But you didn’t want any salmon

yourself, Uncle?”

“My pumpkin pie, you shouldn’t call me

uncle, given your newly advanced years.”

Blushing tired out Aja.

Now that she thought of it, she hadn’t seen

the lord eating any of the entrées. She told him as much.

“I didn’t come to this Banquet to eat,” he

said. “To me, the best seasoning is conversation.”

“But how could you say no to everything? The

kraken, the roc egg, it was all too delicious.”

“Alas, not to me. I’ve lost the knack of

tasting.” His face never changed expression, but the red paint on

his lips had an upward barb on the left side as if he smirked.

“Some would say I never had good taste to begin with.”

“You can’t taste? Is it because of your….”

Aja had to know. If old age had taken away his desire for food, Aja

might never taste again as well.

“My magic,” he said. “After drinking of the

black chalice, all other delicacies are dust in the mouth.”

She squinted up at the lord. Was he telling

her the truth? His features seemed too still and perfect to be

real. He had to be wearing a mask.

Aja asked, “What is your magic?”

“I hope never to show you, my intrepid

truffle.”

The lord lifted one of the wooden cups of

polished ebony. The djinn poured from the amphora. Ribbons of

purple light traveled up the flow of water. She said, “Think of

what you wish to forget, then swallow.”

The lord hoisted his cup. “To be free of

memory’s dead weight, a temptation to which I’ll boldly succumb.

Who will drink with me?”

Solin also had a pour. He balanced his cup

on a crutch and reached to knock it against the lord’s in a

toast.

“To oblivion!”

The lord drank, but Solin hesitated. He set

his cup down untasted.

Why had Solin changed his mind? Aja worked

moisture in her dry mouth to ask, but after five creaking swallows

her parched throat still pained her. “You don’t wish to

forget?”

Not speaking, he tapped his fingers over the

pillow hiding his bad leg.

“You shouldn’t ignore old ladies,” Aja said,

“it’s not polite.”

Solin’s mouth slanted downward on either

side, as hard as a tile roof. “Shouldn’t have let you eat all the

dragonfruit. I shouldn’t have done a lot of things, and I’ve no

right to forget them.”

“You’re not responsible for me,” she

said.

“But I am for my hexes.” He glanced down.

“Forgiveness must come before forgetting.”

He regretted something so much. He had one

sickly leg, and he was a hexer. The three things might be linked.

Aja cracked her mouth open then closed it again. She wouldn’t ask.

She had offended him enough.

The Chef presented the salmon to Solin. Its

steam wafted past him to Aja. She didn’t smell anything, but she

glimpsed a vision of a woman’s face. An arching brow, a tired eye,

a welcoming smile. Was it her mother?