Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (56 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Intriguingly, the lower right-hand corner of

The Setting Sun

remains blank but for a few swipes and squiggles, as if to emphasize that this giant canvas is unfinished and, like the other compositions, still awaits the master’s further ruminations. Yet the rest of the canvas’s 125 square feet have been painstakingly and emphatically painted. The reflection of sunset on water is created with thick slatherings of cadmium yellow in which we see the imprint of Monet’s brush and thick gobs of paint that seem to have been squeezed straight from the tube. The result, as we stand back, is the hot glare of sundown spreading its molten light across a peaceful pond. “To create impalpable matter from canvas and paste,” an art critic wrote of Monet’s works in 1922, “to trap the sun, to focus and diffuse its light.

Quel miracle

!”

48

With our backs to the fiery glory of

The Setting Sun

, we are entranced by keynotes of tender blues, woolly pinks, spongy greens. The first room appears, from this perspective, as a place of calm and quiet meditation, the haven for neurasthenics of which Marcel Proust had dreamed more than a century earlier. But a new note strikes as we pass through the gracefully arching doorway and enter the second room. Here, three of the compositions are flanked by the graceful curves of truncated willow trees showering their branches in fragile, flickering cascades as they

gather us in a sweeping embrace. They are, as Monet intended, symbols of mourning. Not merely honoring—as he had first envisaged on that long-ago November day—the glorious dead of the Grand Guerre, they mark an apotheosis of mourning. It is not difficult to see in them the commemoration of all those whom Monet had lost, from Alice and Jean to Mirbeau and Geffroy, in those years of anguished struggle.

The panels become even more acutely personal as we turn around and see on the entrance wall of this second room the darkest and most unsettling of the compositions:

Reflections of Trees

, the wounded, bomb-scarred canvas. As Paul Hayes Tucker has pointed out, this composition—“dark and haunting...if not slightly disturbing”—is very rarely reproduced because of its gloomily unnerving qualities.

49

It offers what is undoubtedly Monet’s most disquieting vision, a sharp rejoinder to those who might still think of him only as “the great anti-depressant” churning out dappled riverbanks and sun-kissed meadows. The lily pads glow an eerie radium blue, their blooms like candles—like the lanterns of Rollinat’s hobgoblins—against the creep of shadows and the last fall of light. The colors shimmer and seem to float from the wall.

In the midst of this gently fluorescing twilight, at the joining of the two canvases, we see an indistinct silhouette: the sinuous apparition of a willow glimpsed upside-down in reflection, a liquid shadow wreathed in clouds of blue lily pads. Its bifurcated trunk forms an anguished human body, even perhaps a drowned shape passing through the shadowy fathoms. If the other walls of this room speak to us of sorrow and loss, in this wraithlike afterimage we feel the painter’s rage and suffering but also his defiance and resilience. Monet did not believe in God, but he believed in the sanctity of nature, and the forked creature formed by the willow suggests a calvary. It brings with it the promise of resurrection and renewal, of a “sea-change / Into something rich and strange.”

Reflections of Trees

is the most emblematic of all the paintings of those long years of toil and trouble: the self-portrait of a man who, like golden-haired Hylas, was irresistibly drawn into the luminous abyss of the lily pond.

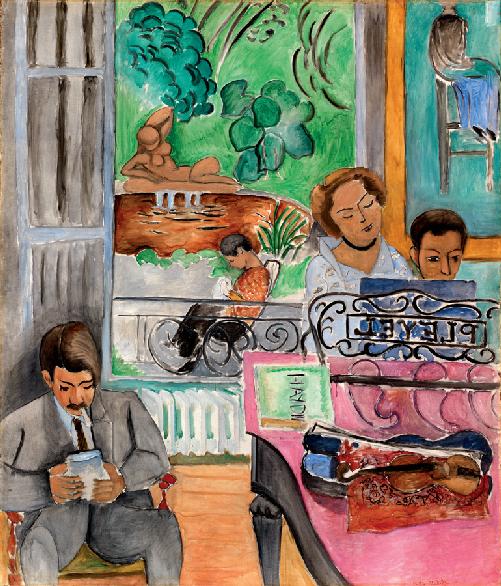

Claude Monet,

Women in the Garden

, 1866 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

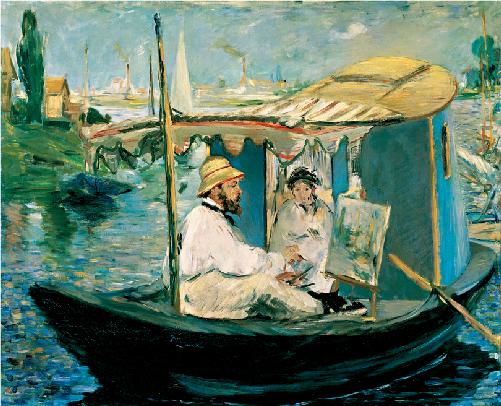

Édouard Manet,

Claude Monet Painting in His Studio Boat

, 1874 (Neue Pinakothek, Munich)

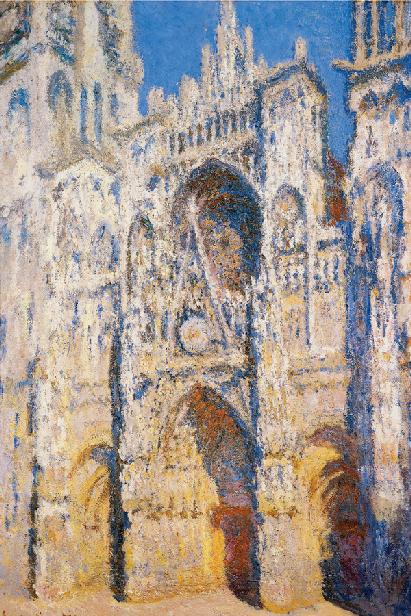

Claude Monet,

Rouen Cathedral: The Portal and the Saint-Romain Tower, Full Sunlight: Harmony in Blue and Gold

, 1894 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

Monet,

Wheat Stacks, End of Summer

, 1891 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

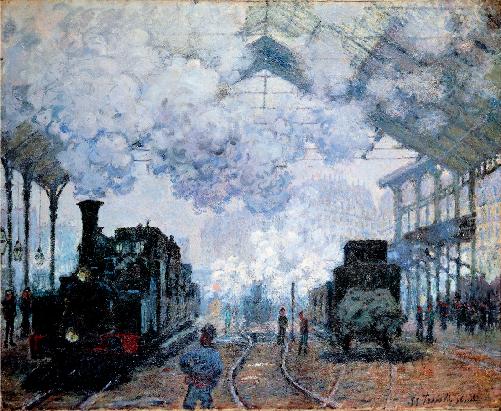

Monet,

The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train

, 1877 (Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University)

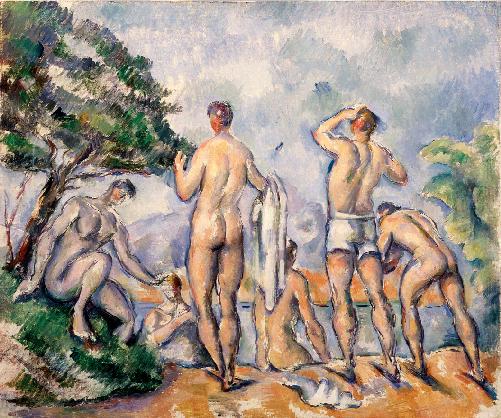

Paul Cézanne,

Bathers

, 1890–92 (Saint Louis Art Museum) One of the fourteen Cézannes owned by Monet.

Monet’s dining room at Giverny, faithfully maintained in the original “Monet yellow”

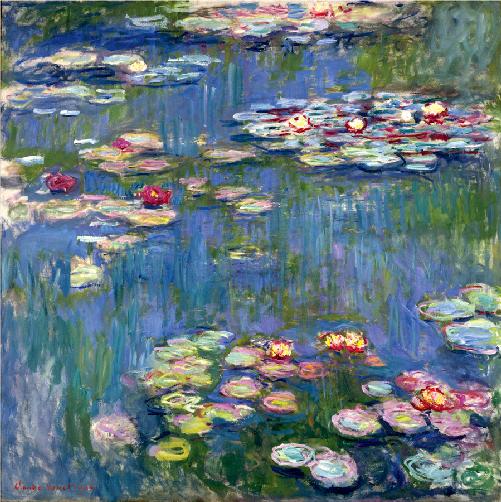

Monet,

Waterlilies

, 1908 (National Museum Wales, Cardiff)

One of the “upside-down” paintings from Monet’s landmark 1909 exhibition at the Galerie Durand-Ruel.

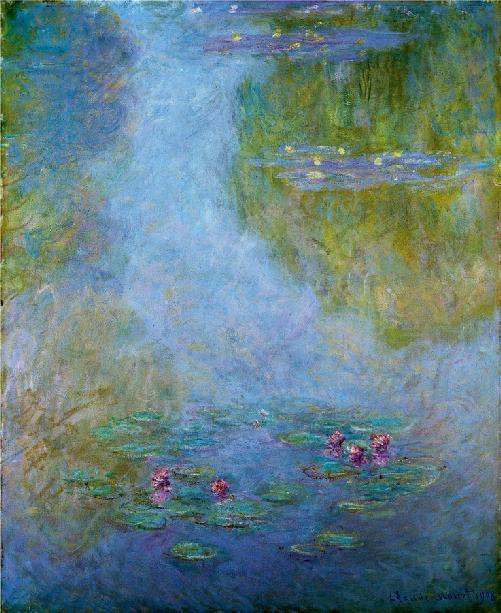

Monet,

Water Lilies

, 1916 (National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo)

The painting for which Kojiro Matsukata paid a record 800,000 francs.