Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (14 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

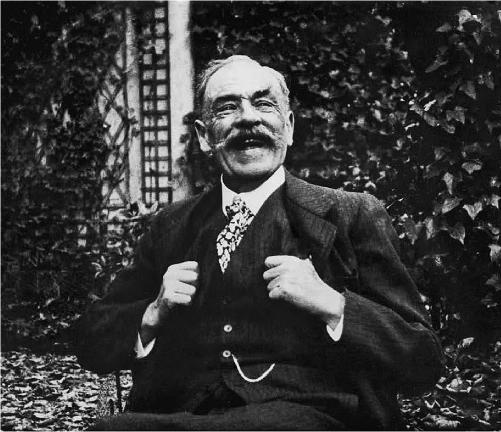

Monet’s great friend, the writer Octave Mirbeau

In his younger days, Mirbeau’s passionate intensity was combined with an intimidating appearance: fiery red hair, fierce, sky-blue eyes, and an imposing physique. A journalist described him as having “the

wide shoulders and the muzzle of a mastiff who barked loudly and bit hard.”

28

One of his eccentricities was a savage-looking dog that he used to parade about Paris on a lead—a beast of mysterious origins (purportedly a dingo) whose tenacious fidelity to its master reflected Mirbeau’s own devotion to friends such as Monet.

29

As a reflection of his gentler side, he also owned a more placid pet, a hedgehog whose death left him bereft.

In the old days, Mirbeau used to bicycle along the Seine to Giverny. By 1914, at the age of sixty-six, he was, sadly, a shadow of his former self, partially paralyzed by a stroke two years earlier. He had become known as the “hermit of Cheverchemont,”

30

able to travel only with difficulty and—more seriously—unable to write. To raise funds for the upkeep of his house, he was reduced to selling his beloved collection of paintings. Three of his Van Goghs went to auction in 1912, including

Irises

and

Three

S

unflowers

, both bought by Mirbeau a year after the artist’s death from Père Tanguy, whose portrait by Van Gogh he also owned. “Ah! How he has understood the exquisite soul of flowers!” Mirbeau wrote in one of the earliest appreciations of Van Gogh.

31

He sold the paintings with much reluctance, although the fact that

Three Sunflowers

was hammered down for 50,000 francs, 166 times what the price he paid for it, provided some consolation.

The visit from Mirbeau, however welcome, may not have been especially cheerful. Convinced that his death was nigh, the stricken writer had taken to telling his friends and visitors: “You won’t see me again. Oh, no! I’m done for!” On one occasion he told Monet: “We won’t see each other again, Monet. I’m finished, this is the end!”

32

His mood was bleak for other reasons as well. He was one of France’s most prominent and articulate antimilitarists, his novels frequently expressing a horror of war, nationalism, and patriotism. The title character in

Sébastien Roch

, for example, denounces patriotism as vulgar and irration al, while military heroism he finds nothing but “a bleak and dangerous banditry and murder.” Sébastien ultimately dies ingloriously on the battlefield, illustrating Mirbeau’s belief that, in wiping out the youngest and strongest, war does nothing but destroy “the hope of

humanity.”

33

Unsurprisingly, the outbreak of war left him despondent. “The war weighs on me,” he was to tell a journalist a few months later. “It haunts my nights and days.”

34

Mirbeau must have been cheered, however, by the sight of Monet’s new paintings, comforted in the knowledge that Monet, at least, could still work even if he himself could not. An essay on Mirbeau, written by a friend and published in 1914, said of him: “Noble of heart and demanding of spirit, he eagerly sought in the minds of men, and in their works, an impossible beauty for which, as a paladin of justice and beauty, he was prepared to break his lances.”

35

Monet was, above all, the artist in whom Mirbeau found this impossible beauty, and for whom he was willing to break his lances. From his pen, over the years, there had issued a constant stream of reassurance and encouragement, especially during Monet’s various periods of crisis. “You are, without doubt, the greatest, most magnificent painter of our time,” he wrote as the despairing Monet canceled his 1907 exhibition and shredded his water lily paintings.

36

And in the summer of 1913 he had gone with Monet to Les Zoaques, joining Guitry’s “affectionate exhortations” for him to take up his brushes again.

37

Fittingly, Mirbeau was among the first to see the beginnings of the grand new project. Monet was eager to show the work to friends. He had invited Gustave Geffroy back in July to see “the start of the vast work,”

38

but on two occasions that month the visit failed to materialize. Nor was he any luckier with Clemenceau, who, as a senator, the chairman of the Senate’s army and foreign affairs committees, and editor of

L’Homme Libre

, was likewise detained in Paris and, in fact, preparing to follow the government to Bordeaux. Meanwhile, Sacha Guitry had remained seriously ill with pneumonia throughout the spring and early summer, and at the start of July he went to convalesce at Évian-les-Bains. By September he and Charlotte were preparing to join the evacuees, arranging a villa for themselves in the safety of Antibes.

What exactly there was for Mirbeau to see—that is, how far Monet’s work had progressed by early September—is difficult to know. Monet claimed in early July that he had been at work for two months

“with no interruptions, in spite of the unhelpful weather.”

39

Scorching temperatures and thunderstorms in early to mid-July gave way to cooler days and frequent downpours toward the end of the month.

40

If he did accomplish more work in July, he appears to have stopped painting altogether in August and September, amid the panic and uncertainty. What Mirbeau saw in those frantic early days of the war was the beginnings of a work that, however impressive, had temporarily been suspended.

BY THE MIDDLE

of September, the threat had eased and the military situation, from a French point of view, looked almost optimistic. The “Victory of the Marne,” in which more than six hundred taxicabs carried reinforcements to the front, meant that the threat to Paris disappeared. “They return home by the road of defeat and shame,” a newspaper exulted of the German retreat from the Marne.

41

The Germans did not, of course, return home; rather, in the middle of September they began digging their first trenches on the northern banks of the Aisne, while the British, on the opposite side of the river, began entrenching themselves along the chemin des Dames: the first muddy burrows of the network that would ultimately stretch from the North Sea to Switzerland. Already the conflict had been christened with names—“La Grande Guerre,” “La Guerre Mondiale”—that suggested its terrible magnitude.

42

After the heart-stopping events of the previous six weeks, an unreal and uneasy life returned to Giverny. The village was still eerily empty of people. “All the world fled,” Monet wrote in October.

43

To a friend in Paris he wrote that he saw no one, “unless it’s the unfortunate wounded, who are found everywhere here, even in the smaller towns.”

44

However, Mirbeau paid him another visit early that month, and Monet reported to Geffroy that their ailing friend was “in good health and very excited by events”

45

—that is, by Monet’s grand new project, on which, however, he had still not resumed work.

In November, Monet made a trip to Paris, his first visit since the outbreak of hostilities. The city presented a sober aspect in the first months of the Grand Guerre. Many evacuees had returned by this

point, and the city was filling with Belgian refugees and wounded soldiers. The wounded were so numerous that part of the Ritz had been requisitioned and turned into a makeshift hospital. Only a handful of other hotels remained open.

46

The streets were largely deserted, the theaters closed, the Louvre empty, the streets dark after sunset. There was virtually no art to be seen anywhere. As a newspaper put it on the day Monet arrived: “Throughout the terrible tests imposed on us by the abominable war, art can hardly raise its voice except to make a complaint. Art is in mourning for the marvels of Louvain, Malines, Arras and Reims,”

47

cities whose art and architectural treasures had been damaged or destroyed. The sole exhibition on offer, sponsored by a Franco-Belgian association, was Henri-Julien Dumont’s “Impressions of War: Senlis in Ruins”—paintings that, as a reviewer declared, “spoke, screamed and wept for justice violated and punishment too long in coming.”

48

The time for blissful and beautiful scenes of ponds and gardens, it must have seemed, had passed.

In Paris, Monet enjoyed a lunch with Geffroy. The pair had been friends since first meeting in September 1880, when they found themselves staying in the same small hotel at the foot of a lighthouse on Belle-Île-en-Mer and Geffroy mistook Monet—with his beard, beret, chunky sweater, and weather-beaten appearance—for a sea captain.

49

That same year Geffroy had started working as a journalist on Clemenceau’s

La Justice

. Like Clemenceau and Mirbeau, he had become an articulate, forceful, and lifelong crusader. According to one friend, he was “the man who puts the just in justice.”

50

To other friends, he was known affectionately as “Le bon Gef.” His “sweet, care-worn face,” as a fellow critic described it,

51

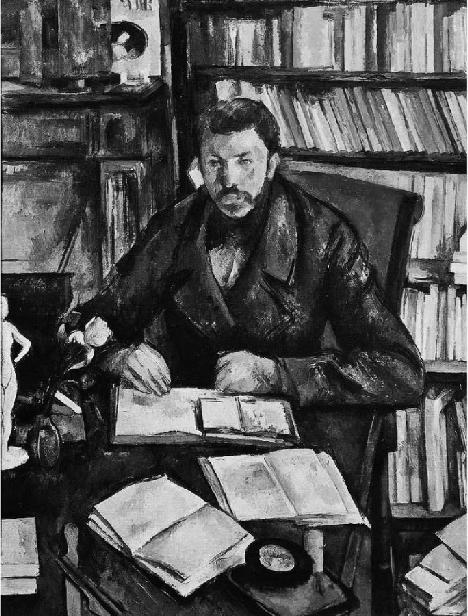

had been painted by Cézanne and sculpted by Rodin. A prolific author of books on artists and museums, since 1908 he had served as the director of the Manufacture Nationale des Gobelins, the tapestry factory in Paris. There he lived in an elegant apartment with his beloved mother, his invalid sister Delphine, and his library of thirty thousand books. One of the many things he had in common with Clemenceau and Mirbeau was the conviction that Monet was one of the greatest artists in history—“among the race of masters,” as he confidently declared.

52

A pleasure denied to Monet and Geffroy during their visit was the company of Clemenceau, who was in Bordeaux running

L’Homme Libre

from a tiny flat with a skeleton crew: three-quarters of the newspaper’s staff had gone to war.

53

Monet had not heard from the Tiger since the first week of the war, when he wrote from Paris: “I am very tense, but I am convinced that if everyone stays in good spirits—and this is what I see around me—we shall do very well. Only it will take time.”

54

That August he had written stirringly in

L’Homme Libre

of the need to set aside political enmity and division: “Today there must be no hatred among the French. Now is the time for us to discover the joy of loving one other.”

55

A few days later he wrote optimistically to a friend in England: “We are experiencing difficult times, but I think we shall come out of it well. The country is admirable. Not a cry, not a song. Nothing but the tranquillity of resolutions.”

56

Portrait of Gustave Geffroy

(1895–6) by Paul Cézanne

This joy of loving and tranquillity of resolutions did not last. By the end of August, when Paris looked ready to fall to the Germans, Clemenceau met with Raymond Poincaré, the French president, who found himself subjected to a spectacularly forceful attack. “He spoke with the hatred and violent incoherence of a man who had completely lost control of himself,” claimed Poincaré, “and with the fury of a disillusioned patriot who thought that he alone could bring victory.”

57

Poincaré was not the only one to suffer the Tiger’s wrath. In 1887, Clemenceau had declared: “

La guerre! C’est une chose trop grave pour la confier à des militaires

.”

58

In 1914 he quickly became confirmed

in his belief that war was too important to be left to the generals. By September he had launched fierce attacks on France’s military elite. He criticized the army’s medical services in

L’Homme Libre

after witnessing wounded soldiers shipped from the front in cattle cars and horse boxes, with the result that many contracted tetanus. However, the government had enacted State of War regulations, suspending civil liberties and granting the military authorities wide-ranging powers to censor any newspapers deemed liable to endanger public order or deplete morale. Clemenceau was accused by one general of waging a “vicious and misleading campaign.”

59

All copies of the newspaper were seized and

L’Homme Libre

was suspended for a week. The paper eventually reappeared, albeit with a sarcastic new name on the masthead:

L’Homme Enchaîné

. The “Free Man” thus became “The Man Enchained.”