Mad Dog Moxley (3 page)

Authors: Peter Corris

There were exceptions to this general rule of low-level criminal activity, notably the sly-grog trade and starting-price (SP) bookmaking, both of which were exacerbated by the Depression. Poor people could not afford the admission prices at the racecourses and bet small amounts at known locations. Licensing laws were tight, opening hours were limited and drinkers and suppliers were resourceful. From the press and the pulpits came frequent denunciations of prostitution and drug-taking as well as approval of the harsh methods adopted by the authorities, but criticism of gambling and drinking was soft-pedalled at the official level. Temperance societies abounded, but even the most hidebound conservatives could see the disastrous consequences of the

Volstead Act

in the United States.

The picture has to be painted in different shades. Wendy Lowenstein's informants spoke of women forced into prostitution to support their children and a good deal of petty thieving. One woman described how her father stole from the market, using his children as a diversionary tactic, simply to feed his family. She added that people who were otherwise scrupulously honest would not hesitate to steal food if an opportunity presented itself.

Violence often flared when police evicted tenants from houses they had occupied for years, even generations. As John Birmingham notes in his lively âunauthorised biography' of Sydney,

Leviathan

, organised protesters fought a pitched battle against police in Newtown with serious injuries on both sides. The Unemployed Workers Movement formed flying squads of mostly young men, termed âpolitical bushrangers' by their opponents, willing to confront the police. Less potent and damaging resistance was offered in other places, particularly at the heart-rending sight of a family watching as its goods and chattels were hauled away due to failure to keep up with its time payments. J T Lang's

Moratorium Act

, which outlawed the repossession of goods, mitigated against this but evictions continued and many families spiralled down from rented homes to boarding houses to the shanty camps.

There was panic in Martin Place when the Government Savings Bank of New South Wales, where 40 per cent of Sydney's citizens had placed their savings, suffered a run from depositors and closed its doors. Briefly, before the Commonwealth Bank undertook to back the state bank â and before depositors were convinced of this â some were willing to sell their savings passbooks for half the amount registered just to get some ready cash.

Survivors of the Depression in Sydney agree that insecurity was a significant feature of their lives throughout the period. Jobs were at risk and so, therefore, were housing, health and relationships. Something frequently commented upon by these people was their fear that things would never change, that the harsh circumstances would go on forever. This created not only insecurity and anxiety but also despair, and suicide was not uncommon.

Against this, for those with a little disposable income, some forms of entertainment were cheap. At a time when many suburbs had a cinema â sometimes two â Moxley, like thousands of Sydneysiders, âwent to the pictures'. The âtalkies' were still a novelty, and sixpence gained admission to the back stalls for a double feature, or at the very least a full program of newsreels, shorts, cartoons, serials and a feature film. It is known that Moxley read American crime novels; it's possible that he enjoyed the American crime films of the time, such as

The Public Enemy with James Cagney and The Criminal Code

with Walter Huston.

Admission to Sydney's two boxing stadiums at Leichhardt and Rushcutters Bay was cheap and there was no dress code. Both venues were full to capacity for the epic bouts between middleweights Ron Richards and Fred Henneberry and for the performances of such world-ranked national champions as Ambrose Palmer and Jack Carroll.

Although rugby league in Sydney never reached the popularity enjoyed by Australian Rules football in Melbourne, with admission at 1 shilling, attendance at matches was possible for many, if not every week. The competition continued through the Depression, although, according to the entry in

The Oxford Companion to Australian Sport

, revenue was low throughout the â30s. Nevertheless, in 1932 a record crowd of 70 000-plus saw the first Test between Australia and England at the Sydney Cricket Ground.

There was, in addition, one ongoing sign of hope: the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Begun in 1924, the building of the bridge provided employment for many hundreds of men over the following decade. The work was dangerous; 16 men were killed during its construction. Despite this, as the two arches stretched towards each other over the water, they seemed to offer some promise for the future. The opening of the bridge in 1932 was attended by thousands of Sydneysiders and others who had come from the country and interstate to witness the event. A temporary grandstand was erected and refreshments were sold to the crowd. Those who were present recall a carnival atmosphere and a feeling of pride in their city, however difficult their circumstances might have been.

The Great Depression exhibits many contradictory features. While the building of the bridge provided regular, well-paid if dangerous work to hundreds of men, there was to be a downside. As John Birmingham notes, the riggers and welders were laid off after completion of the job and most of them failed to find employment again until required at Garden Island for the building of warships in World War II.

The brand new bridge figures in the tragic story of the Moorebank killings. William Cyril Moxley paid his toll and crossed it in his attempt to evade the authorities. William MacKay, the chief superintendent of the New South Wales Police Force, who knew Moxley well and had used him as an informant, was the officer who dragged Francis de Groot, the man who had slashed the opening-ceremony ribbon ahead of the premier, from his horse. The moment was captured in a piece of contemporary doggerel:

MacKay got very ferocious. He said, âYou bally hound!'

And grabbed him by the wish-bone, and threw him to the ground.

A fat dame in the grandstand said, âOh, you horrid brute,'

Up came a Black Maria and in went old de Groot.

THE KILLER

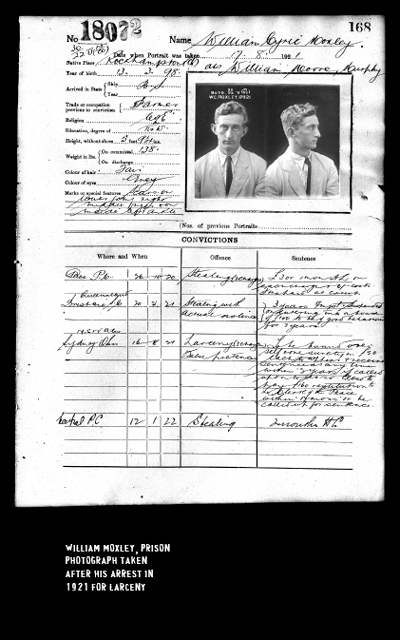

A very cunning and agile thief

POLICE NOTE ON WILLIAM CYRIL MOXLEY

William Cyril Moxley (oddly, the name on his birth certificate is Silas William, but he was known as William Cyril, apart from his many aliases, all his life) was born in Rockhampton, Queensland on 13 March 1899. His father, Walter Sylvanus, born in Queensland, was a commercial traveller; his mother, Jane nee Hudson, was English. Moxley was the fourth child after a brother and two sisters.

Nothing definite is known of Moxley's early life. He claimed that his father was shot dead when he was a child and that he had accidentally shot and killed his brother when he was nine years old. Truthfulness was not one of Moxley's attributes, and at the time he made this claim he was attempting to establish grounds for a plea of insanity. Queensland and New South Wales registers of deaths in the relevant period do not bear out Moxley's statement. In fact, his brother fathered two children in 1909 and 1913.

As was common for working-class children until well into the 20th century, Moxley left school at what would now be considered a very early age. His first job, in Sydney in 1912 when he was 13 years of age, was as a telephone operator at Sydney University.

A later â sensationalist â newspaper report describes Moxley as âsemi-moronic', but this was not the case. In his prison records under âEducation' is entered âRead & Write', indicating a basic education. To judge by his statements in the dock and from reports by others on what he said to them at various times, Moxley spoke and wrote slightly ungrammatically, but fluently and with a reasonably wide vocabulary. His spelling was uncertain and his speech was sprinkled with criminal argot. His religion was given as Church of England.

Moxley applied to enlist in the army on 4 May 1918 and was accepted nine days later, presumably after checks on the information he supplied. He was then 5 feet 11 inches tall and thin at 10 stone 6 pounds and with a 31-inch chest expandable to 34 inches. His complexion and hair were fair and his eyes were grey. With jug ears and slightly protuberant eyes, he was homely. Gold fillings showed in his teeth â not a good look now, but acceptable then. A medical officer found him free of disease, able to see adequately with each eye, free in the limbs and joints and with a healthy heart and lungs.

Years later a doctor testified that he had examined Moxley when he was 14 and then again at age 18. On the first examination he found him to be suffering from long-standing gonorrhoea; on the second occasion Moxley had âprimary syphilis'. If these diagnoses were correct (that of syphilis was later confirmed), it shows that Moxley was sexually active at an early age, unless the diseases were congenital. Both diseases usually display outward signs, so either the medical officer's examination was superficial or Moxley was an unusual case.

He gave his occupation as driver. He had a scar on his left hand and on his ankle. He claimed to have served as an infantryman in the cadets for five years and to never have been convicted of a criminal offence. His mother was registered as his next of kin and she gave permission for him to enlist. All recruits under the age of 21 required parental consent, although this was often circumvented. By whatever means, Moxley's father had died by this time.

Moxley declared himself willing to be inoculated against smallpox and to understand that his pay would be 10 shillings per day with no extra allowances as he was single with no dependants. He took the oath to serve âour Sovereign Lord the King' for the duration of the war and for a further period if so ordered. He signed in a firm, fluent hand.

Moxley was not a model soldier. Even before his unit â the New South Wales 13 th Reinforcement â embarked for Britain from Sydney on 17 July 1918 aboard the army transport

Borda

, he committed the first of a series of offences that formed a pattern in his service record. He was AWL at Blackboy Hill, Western Australia, for three days. Did he have second thoughts about enlisting? Whatever the reason for his absence, he was given 168 hours of detention and docked ten days' pay. At sea he was found guilty of âwillful disobedience of an order' and of âmaking an improper reply to an NCO'. He was given 96 hours detention.

The

Borda

arrived in Britain on 27 September 1918, just short of seven weeks before the war ended, and Moxley did not see active service. He was stationed at various locations around Britain and appears to have given no trouble for almost a year. However he was AWL on two occasions in late 1919, âapprehended in London' on the second occasion and âremanded for court martial'. His penalty was the âforfeiture of pay for the period of his absence'.

On 27 August 1919, at the St Giles Registry Office, Moxley married Ada Murphy, 20, then a waitress at the Elephant and Castle restaurant. Moxley's address was given as Shakespeare Hut, Gower Street, Bloomsbury. Not surprisingly given his earlier record, he had remained a private. Some of his absences may have been to spend time with his wife. On 20 December 1919 he was granted âindependent leave subject to recall'.

Moxley may have been something of a malingerer. At one point during his time in Britain he attempted to evade duty by complaining of an old shoulder injury â a broken clavicle. An unpersuaded medical officer declared him fit for duty. He was evidently a poor correspondent. On 15 December 1919 his mother wrote to the army saying she had had no news of her son (curiously she calls him her brother, although the registration number she gives for him is accurate) âfor months'. The army replied that it had no recent reports of him.

Moxley was scheduled to be shipped back to Australia on the transport

Runic

, but he did not turn up. He returned to Australia aboard the

Osterley

which arrived on 3 March 1920. A medical examiner declared Moxley disease and disability free but still discharged him on 31 March 1920 as âpermanently unfit for General Service', presumably on the grounds of character.

Within a few months of being demobbed, Moxley was in trouble. On 26 October 1920, giving his occupation as farmer and measuring an inch and a half shorter and 10 pounds lighter than when he enlisted, he was convicted in Glebe on two counts of theft. Given the option of a month's imprisonment on each charge or paying a fine of £6 with 6 shillings costs, he paid the fine. His next court appearance was in Brisbane on a more serious charge: âstealing with actual violence'. He received a three-year suspended prison sentence, with a good behaviour bond of £300. This seems lenient and perhaps reflects consideration given to his military service, undistinguished though it was.

Three months later Moxley was convicted in Sydney of three charges of larceny and false pretences and bound over in a £50 surety. He undertook to pay £10 restitution within 12 months or serve a three-year sentence; the sentence was to be served if he offended within three years.

With his occupation now listed as carpenter, Moxley embarked with three accomplices on a spree of house, warehouse and factory breaking which netted them thousands of pounds worth of goods. The gang had a hideout in Abercrombie Street, Redfern, which the police raided. Shots were fired and Moxley's attempt to escape over the roof was frustrated.

The result was a three-year sentence with hard labour for a succession of stealing and receiving offences and for the possession of an unlicensed pistol. He apparently served this sentence because his last appearance in court before his trial for the murder of Dorothy Denzel and Frank Wilkinson was in Sydney in 1925 when he was convicted on one count of breaking and entering a dwelling with an intention to steal and for a similar offence in respect of a factory.

A note attached to his police file described him as âan expert shop and house breaker'. His

modus operandi

was to force the doors of shops when they were closed and of houses when unoccupied or to break the leadlights of doors or windows. On at least one occasion he varied his method; he hid himself in a shop until after closing time, then admitted an accomplice. The pair allegedly stole goods to the value of £1500 and transported them in a horse-drawn sulky.

The same note described him as âa very cunning and agile thief' who consorted with vagrants and frequented hotels and billiard halls. The system had exhausted its patience. Moxley was sentenced to two years and declared a habitual criminal. This meant that any future offence would draw an indeterminate sentence and impose severe restrictions on his conduct and movements.

William Cyril Moxley, alias Moore, Murphy and Fletcher (the name of the woman he boarded with) and Hudson (his mother's maiden name), also Harris and Swan, disappears from the public record for the next five years. But there is no reason to believe that he became a law-abiding citizen. Moxley failed to appear in the Campsie Court House in April 1932 on a charge of breaching trade regulations. This probably referred to Moxley's habit of demanding a bond from those he employed in his timber carting business when they used his lorry to make deliveries and then not returning the money at the end of the contracted period. Moxley continued to play a role in the criminal underworld and, dangerously, at least part of the time, as a police informer.