Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (7 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

With Dunkirk no longer in Allied hands, the German forces turned their attention to the rest of France.

L

’ Armée de l’ Air

and the remaining

RAF units were driven ever westwards. It was now that the adage was born: ‘the ultimate in air superiority is a tank in the middle of the runway!’ Allied communications broke down, command chaos reigned and effectiveness was eroded. Hard fighting still took place, but this became increasingly spasmodic. The final

Jagdflieger

victory of the campaign came on 24 June when a Bf 109 shot down a Potez 63 over Montelimar. Hostilities ceased the next day.

Experten

Top scorer in the French campaign was Werner Mölders with 25, amassed in the course of 127 sorties. He was closely followed by Wilhelm Balthasar with 23. Trailing well behind, although both were relatively late starters, were Helmut Wick with 14 and Adolf Galland with 13.

WERNER MÖLDERS

With 14 victories in Spain to add to his 25 in France, at the close of hostilities in June 1940 Werner Mölders was by far the most successful of the German fighter pilots. Progress had been slow at first, mainly due to lack of opportunity, and his first ten French victories had taken 78 sorties. They included two Hawk 75s, a Blenheim, three MS.406s and four Hurricanes, one of which he misidentified as a Morane.

Once the

Blitzkrieg

commenced, opportunities increased and the next fifteen victories, one of which was a Spitfire, came in only 49 sorties. But on his 128th sortie, in the afternoon of 5 June 1940, came near-disaster. Mölders’ own account appeared in

Der Adler:

There are aircraft overhead which we cannot identify; we climb to 7,000m. German Messerschmitts! So we lose altitude and turn towards home. Suddenly we encounter six Moranes. I line up for an attack from astern. As I approach I spot two other

Staffeln

of Messerschmitts who are engaging the same opponents from above and astern. They were in position first, so I pull away to see what happens.There is the usual dogfight while several Moranes stand their ground bravely and fight. A burning Messerschmitt crashes to earth; the pilot bales out. I watch for a while, then attack a Morane which keeps making steep turns as three Messerschmitts fire at it in vain. Briefly I get my enemy in my sights. He immediately swings away, but he has still not had enough. Suddenly he pulls up underneath me; I lose sight of him under my wing. There he is again, down below, behind me and off to one side. Damn it—he’s still shooting too, although very wide.

I turn briefly, then pull sharply up into the sun. My opponent must have lost sight of me, for he turns in the opposite direction and disappears to the south.

Below me, two Messerschmitts are still tangling with the last Moräne. I watch the fight as the Moräne tries to escape at low level, evading their fire by jinking. A backward glance, another above and behind me; the sky is still full of turning Messerschmitts. I am at about 800m. Suddenly there is a bang and a flash in my cockpit, and I black out. The engine is shot to pieces, the control column lurches forward; we’re headed straight down. Get out now, otherwise you’re finished.

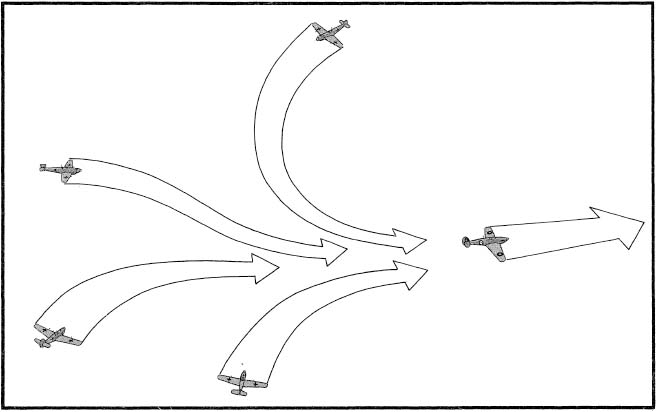

Fig. 8. Curve of Pursuit

The favoured attack from astern almost invariably involved a curve of pursuit to take the attacker from his start point to a firing position. Usually done by keeping ones nose on the target, this normally resulted in a tail-chase, as seen here. A far better method was to keep the target at a constant angle through the windshield sidelight until the range closed.

Mölders had suffered the fate which he dealt out to so many: he had been surprised and bounced from out of the sun. His victor was

Sous-Lieutenant

Pommier Layrarges, flying a Dewoitine D.520 of

GC 11/7,

Cornered by three Bf 109s immediately afterwards, the young French pilot did not survive to learn the identity of his eminent victim. Parachuting down into French territory, Mölders was taken prisoner, only to be freed at the armistice three weeks later.

‘Vati’

(Daddy) Mölders demonstrated an iron will to overcome motion sickness in his training days. He was also a tactical thinker of considerable ability and did much to get

Jagdflieger

tactics right in the early days. To him must go much of the credit for developing the four-aircraft

Schwarm

which was so superior to the three-aircraft Vic of other nations, although, as noted earlier, the initial steps were taken from necessity rather than preference. Perhaps his most important contribution to air combat was his care of the pilots under his command, in particular his credo: ‘The most important thing for a fighter pilot is to get his first victory without too much trauma.’ Virtually ignored by most other fighter leaders, this advice has an importance which cannot be overstressed. Fear in combat is entirely natural, but it has to be overcome. If in the early days it is allowed to build, it can destroy the confidence of a young pilot to such an extent that either he cannot continue to fly or he becomes so defensive-minded that he is easy meat for the opposition. If, however, he is allowed to gain confidence in easy stages, he will become an asset, but not before. We shall meet this proposition again and again in coming chapters, as we shall meet Werner Mölders himself.

Mölders flew throughout the Battle of Britain (apart from a brief interval as a result of being shot down and wounded), opposed RAF incursions over Occupied France in 1941, then flew during the early days

on the Russian Front. Although a first class marksman, he preferred to get in close when possible before shooting, and he had a tendency to use his machine guns only. With his score at 101 (not including his 14 Spanish victories) he was grounded in July 1941 and appointed General of the Fighter Pilots. He died in a flying accident in November of that year.

WILHELM BALTHASAR

Whereas Werner Mölders was the highest scorer during the French campaign as a whole, he was eclipsed during the

Blitzkrieg

by Wilhelm Balthasar,

Staffelkapitän

of

7/JG 27.

Balthasar had early shown a talent for mass destruction: of his seven victories in Spain, four were gained in a single action. His best day in France came on 6 June when he was credited with nine French aircraft shot down, although these were not all in a single action. His total at the surrender was 23, with many others destroyed on the ground with strafing attacks.

Balthasar was a dedicated mentor of young fighter pilots, an example of his methods coming during the French campaign when he spotted a strange fighter below and to his right. Its camouflage scheme was unfamiliar, which caused him to identify it as English. At once opening a running commentary for the benefit of his young pilots, he announced that they should watch carefully as he shot it down. First turning right to allow the ‘bogey’ to draw ahead, he then reversed his turn to take up a curve of pursuit (

Fig. 8

), dropping his nose to complete a classic bounce from above and astern.

Meanwhile Adolf Galland, flying in the vicinity, listened admiringly as Balthasar commented in unflattering terms that the Englishman seemed to be asleep. The only aircraft in his vicinity were a

Schwarm

of Bf 109Es high on his left. But suddenly he noticed that its leader had broken away and was making an attacking run on him! With a start, Galland realised that

he

was the ‘Englishman!’ As he was on the same radio frequency, a quick transmission averted what could have been a disaster. Faulty aircraft recognition has always been a feature of air combat. In this case, matters were not helped by the fact that Galland’s aircraft carried an experimental camouflage scheme, which misled Balthasar.

Balthasar went on to lead

III/JG 3

in the Battle of Britain but found that success over England was harder to come by. With his score at 31, he was wounded in combat with Spitfires of No 222 Squadron and as a result was off operations for several months. In February 1941 he was appointed

Kommodore

of

JG 2

on the Channel coast, which he led with distinction until 3 July of that year. On that date he was air-testing a new Bf 109F near Aire when he was bounced by Spitfires and killed.

| 2. THE BATTLE OF BRITAIN |

In its previous campaigns, the

Luftwaffe

had been used as an adjunct to the Army, with the

Jagdflieger

tasked primarily with gaining and maintaining air superiority in support of surface operations. Deep and rapid penetrations by armoured forces had considerably eased their task by disrupting supply routes and communications and by threatening Allied airfields. But with the

Wehrmacht

now halted on the Channel coast, the

Luftwaffe

was forced to operate autonomously.

At first its brief was merely to keep up pressure on the recalcitrant islanders while peace terms were negotiated. When this failed, it was called upon to create conditions suitable for the invasion of southern England. Hitler’s Directive of 16 July 1940 stated: ‘The English air force must be eliminated to such an extent that it will be incapable of putting up any substantial opposition to the invading troops …’ The stage was set for the world’s first solely aerial campaign.

The situation was totally unlike anything ever envisaged by the

Luftwaffe

High Command. They faced a numerous, well-trained and resolute opponent equipped with fighters at least as good as their own. Moreover, that opponent possessed a fully developed detection and reporting system based on radar and ground observers, coupled with a sophisticated system of fighter control which would severely curtail the advantages of initiative and surprise traditionally held by the attacker.

At the start of the battle, RAF Fighter Command was organised into three operational areas or Groups, increased to four at a very early stage: No 11 Group covered London and the south-east, No 10 Group covered south-western England and Wales, No 12 Group was responsible for the defence of East Anglia and the Midlands and No 13 Group covered northern England and Scotland. Each Group was responsible for the defence of its own area, for which it exercised a centralised command

system, although this was sufficiently flexible to allow squadrons from one Group to support its neighbours. Control of individual squadrons in combat was exercised from sector stations within the Groups. For technical reasons, only four squadrons could be handled by each sector station at any one time; however, the squadrons were not confined to their own sector, but could range freely anywhere in the Group area or, if requested, into adjoining Group areas. The keynote was flexibility.

The front line of the detection and reporting system was a chain of radar stations looking out to sea. These could detect raiders at considerable distances and give accurate positions for them, but were less accurate as to height and numbers. Once the raiders crossed the coast, they were tracked by observers. All reports were made to a filter room, where the situation was clarified and passed to Group Headquarters. Group then instructed the sector stations which squadrons to scramble and which raids to intercept. The most advanced system of its time, its only fault was a time lag of about four minutes—representing a distance of about twelve miles for the average bomber formation—between the initial sighting and the plot appearing on the operations room tables. Fighter controllers had therefore to allow for this lag when guiding their squadrons into action.

No 11 Group deployed five Spitfire, thirteen Hurricane, one Defiant and three Blenheim squadrons at the start of the battle, from seven sector stations. No 10 Group contained three Spitfire and two Hurricane squadrons. This was slightly less than half Fighter Command’s total strength: 28 more fighter squadrons were deployed in Nos 12 and 13 Groups. By this time the Blenheim squadrons had largely been relegated to night fighting.

RAF fighter squadron tactics were inferior to those of the

Jagdflieger. A

typical squadron formation consisted of twelve aircraft made up of two Flights, each consisting of two sections of three which flew in tight Vics. Experience in France had led to the adoption of weavers, either a section or individuals, who flew above and astern of the formation to guard its tail, but experience showed that weavers were far too vulnerable and they were soon discontinued. As the battle progressed, some squadrons started to use pairs. A section of four in loose line astern and all aircraft weaving was favoured. This was far better than the Vic, but the

Jagdflieger

were not impressed, referring to it as the ‘

Idiotenreihe

’, or ‘idiot’s file’!