Louise (5 page)

Authors: Louise Krug

When Claude gets back to the apartment Louise is watching a crime show. She begs him to please not leave her alone. “If a serial killer breaks in, how would I defend myself?”

Claude sees she is serious. He starts yelling. He gets close to her neck, saying she is a bloodsucker, that he is no nurse. Why doesn't she try to help herself? Why doesn't she do something to improve her situation instead of just lying around? She throws her shoe at him. He slams the door.

The office is empty. He sits in his boss's leather chair. The phone rings and rings, but he does not answer. He switches on the computer. He stays there all night.

W

arner and Janet email.

The emails begin with “Hi” and “Dear.” They end with “Best.”

One thing about the trouble with their daughter: It has made them want to be kind.

T

he main industry in Janet's town, Iola, Kansas, is a chocolate candy factory. There is also a defunct rubber plant.

When Janet sees Louise helped off the plane by an attendant she is shocked. Her daughter is still wearing an eye patch. She has a cane, and her limp is worse. Her T-shirt and sweatpants look like she's been wearing them for a week. Louise is crabby and teary and can't even snap her right fingers together anymore.

Janet feels guilty. Her shirt is crisp and clean. Her hair is curled under and held back with a headband. She does a yoga video every day and has an exercise ball. She rarely gets sick. Louise has very little luggage. Janet grips her daughter's arm and leads her to the car.

People around town have filled Janet's house with gifts for Louise: a stuffed toy lamb, a framed poem about Jesus, a sign to hang over a doorknob about staying strong. Janet has opened piles of cards, most of which contain pre-printed phrases such as, “We are praying for you,” “Everything happens for a reason,” or “God has a plan.” Louise had announced that she does not believe in God and is irritated by people who do. Janet goes to church, but seeing Louise like this, she has to wonder.

Louise walks past all the gifts and turns on the TV.

â¢

Claude calls Louise, but not as often as he should. She can't hear that well. He keeps having to repeat: “I miss you. I love you. How are you feeling?” Louise says Claude should send her more letters and packages, that he should buy one of those video cameras he can hook up to his computer, that he should always answer his cell phone when she calls, no matter what. She reminds him of the sweet things he used to do for her, like the time in college when she flew out to visit him, and he blindfolded her outside his house, a white duplex on a little street, saying he had a surprise. It had been night, and the air had smelled like a candle. You could hear the ocean and the neighborhood was quiet. He took her by the hand and led her up the stairs, carefully, so she would not fall. There was a trail of rose petals leading to the bedroom. All the lights were off and little votive candles made a heart shape on the floor. A bubble bath was filling up. “It had been like a dream,” she says to Claude now. “It had been what every girl wanted.”

He wonders how she had been seduced by such a romantic cliché. He had seen the whole routine in a movie once and done it for other girls before Louise. He wonders if she's lost all her irony.

Claude hangs up feeling tired and hungry. Louise sends him a long email that he can hardly read, huge blocks of rageful text with almost every word misspelledâthe result of her typing with one hand, and the drowsing effects of the medication, he guesses.

â¢

The Montecito planning commission is beginning to like him. Its sleek members invite him to play tennis and go on fundraising beach walks. A woman named J'Ayme (i.e., “Jamie”) Brenner, a realtor of beachfront houses for celebrities, asks him to brunch one Sunday. The place usually has an hour-long wait, but of course not for her. Over

fruit, coffee, and smoked salmon, J'Ayme tells Claude about a star who is moving to the area and planting an organic herb garden.

“Perfect story material, and you're the only one who knows!” J'Ayme winks. “I'll give you all my exclusives.” She leans across the table and asks Claude if she has something in one of her eyes. Her breasts hover over the salmon.

The apartment is now Claude's. He smokes inside, and leaves spilled corn chips on the floor. He plans to invite some guys from the office over soon to watch a basketball game. They'll have beers, order a pizza.

Claude goes to Butterfly Beach to write a story on a cancer benefit. Its mascot is a teddy bear. He is surrounded by women in bathing suits with metal belts and leather fringe. A woman in sunglasses and a white one-piece talks to him about the foundation. There is a large hole in the fabric that exposes her stomach. Claude nods and writes in his notebook. Trays of free drinks, called Teddy-tinis, are being passed around by sweaty waiters in tuxedos.

“Cancer does not stop in a financial downturn,” the woman says to Claude.

Claude thinks about touching her stomach. Her skin would be warm.

W

hen I step outside to pick up a package on the front porch I think of what I must look like to the people who live on my mother's street. My face is faded. My pink sweatpants are stained with cereal bits and coffee spills. I seldom wear a bra. I think about what would happen if Claude saw me like this. We would both be ashamed. I want him to be here but at the same time I do not. I don't know what we would do. I don't go on walks here like I did with my father in California. Iola is small and the houses are close together. It's not like Santa Barbara with the boutiques and gardens and eucalyptus trees. No one walks anywhere unless they have a destination.

The floor in my mother's house is waxed oak. It is filled with heavy dark furniture that once belonged to my grandparents, and my mattress rests in a giant, carved maple frame. My arms and legs are shrinking from lack of use. They are all bruised, and the bruises look like fingerprints. My hip bones are purple from doorways and corners.

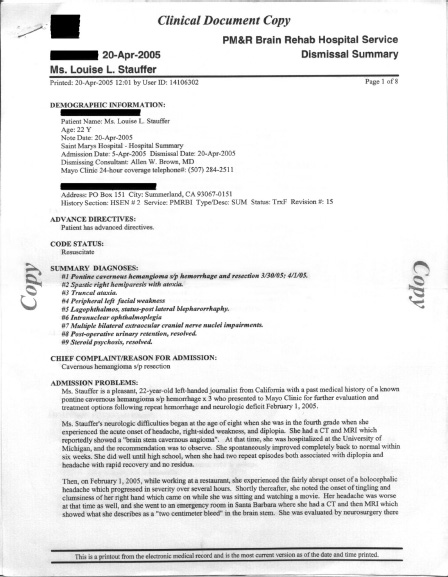

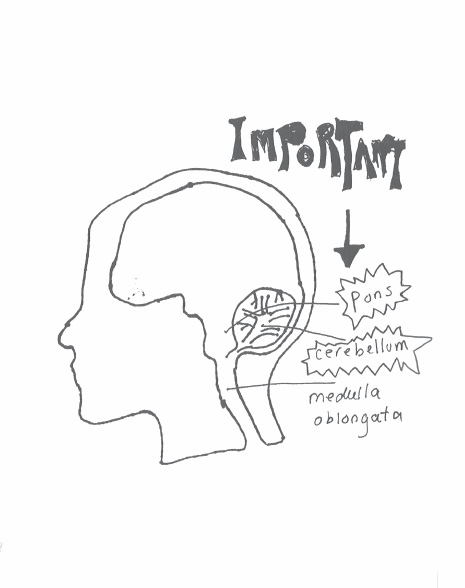

While my mother is at work, I sit in the computer room upstairs. There is only a small desk, walls of books, and a roller chair that gets stuck in the carpet. For the first time, I do a Google search of “cavernous angioma.” What comes up scares me. On message boards, mothers write sad posts about children who have died from what I have, or who have severe brain damage from the craniotomy it takes to remove it. The Angioma Alliance puts on conferences all over the

country. I imagine my family attending one, seeing hundreds of people who look just as dreary and wadded up as we do.

At my mother's I watch a lot of TV.

The O.C.

and

Laguna Beach.

Anything about wealthy teenagers in California with boyfriend problems. My mother thinks I'm torturing myself, but watching beautiful people with petty problems helps me feel superior, somehow.

I find a stack of photo albums in the computer room and cannot resist looking through them. I hardly recognize that girl with a beer in her hand wearing a peacoat on a snowy balcony, or that one, dancing in a bright blue dress with a boy whose hands clutch her satin behind. So many pictures of me in Italy standing alone in front of some statue, some church, some ruins, grinning at nothing.

I had grown up in the typical way and had typical photos to prove it, but they were not promises for a typical life.

I

t is early spring, and the big, empty sky is gray. There are no hills, and small black dots are cows. At the grocery store, real farmers with overalls and hats buy food just like everybody else.

Janet washes Louise's clothes: pajama pants and old T-shirts from Tom and Michael's drawers. Michael, in his senior year of high school now, is hardly ever around. He brought a friend over a few weeks ago, and Louise had stayed in her room the whole night, shouting at Janet when she knocked on the door. Tom is away at college, a two-hour drive away. He says he will visit soon. Janet's boyfriend lives even farther, and has a new grandbaby. So mostly it is just Janet and Louise.

Janet stacks the dishes in the dishwasher. There is not much else for her to do.

â¢

Janet decides: Enough of this. She takes Louise to a physical therapist. No one has told her to do this, but it seems logical enough. Louise can tolerate being in a car now. The gym is a white, cinderblock building off the town's main street. Weights, blocks, and bands sit in bins. The physical therapist looks like a college kid, but he says he is married with three children. Janet explains Louise's situation, and the physical therapist says maybe he can help.

He has Louise step up a set of wooden stairs built into

the wall, then down. He has her curl weights, touch her toes, do squats against the wall. Janet is hopeful. She has always had confidence in athletics and sweat. She used to run half marathons and do aerobics, and now works out on the elliptical machine in her basement every day after work. She always pushed her children to do sports growing up because she thought it would make them grow into fit, disciplined adults. She didn't want them to be lazy.

The physical therapist stands a few feet away and watches a baseball game on TV.

When the session is over the physical therapist gives them a laminated packet of illustrated exercises. The first three are noted to especially help patients with a rotator cuff injury. Janet and Louise look at one another. A rotator cuff injury?

In the parking lot, a group of boys in basketball shorts glance at Louise, then quickly look away. There was a time when boys like that would have made something out of Louise.

They don't bother going back.