Lost Worlds (13 page)

Someone was coming toward me. A tall thin man silhouetted by the lights. I managed to haul myself out and leaned against the rear fender, clinging on to the truck for support.

“A good drive, yes?”

I tried to say something witty, but my mouth was dry and caked with grit. What came out was somewhere between a croak and a grunt.

“I am Francisco. Welcome to the

hato

. Hugo Estrada is my father and he will meet with you later.”

I smiled and nodded.

“Have a wash. Then dinner. Leave your bags. Someone will bring them.”

Sounded fine with me.

There were twenty rooms at the lodge, all previously used to house ranch hands. Mine overlooked a tree whose upper trunk was encased in a bulbous five-foot-high termite nest meticulously shaped out of mud and straw. The lights from the lodge also illuminated the wings of a small plane in an adjacent field, a very convenient form of transportation in this wilderness. The moon was out now, large and low on the horizon, bathing nearby trees and the endless plain beyond in silver light.

In the shower the layered dust on my head and body coagulated into rivulets of mud. A reflection in the cracked mirror made me look like a swamp thing newly emerged from the bog. Not a pretty sight.

Dinner was a splendid affair. The Estradas—the father, Hugo, and his wife, Beatrice, his son, Francisco, two daughters, Carmen and Ixora, and their children—greeted me like a lost relative, offered me a choice of cold beer or fresh fruit juices, and led me to the buffet table set under the stars in the outdoor dining area. Due to bad planning on my part I hadn’t eaten since the morning and was ravenous. And here I was, faced by a feast of soups and entrées of fried fish, steak, chicken in hot sauce, pastas, rice, fruit, and salad, all served with home-baked breads and little

arepa

loaves. Hugo, the stocky don in his early seventies, with a broad white mustache, twinkling eyes, and a ready smile, followed me along the buffet table. “Take more,” “Try the bread,” “Don’t miss this,” “That’s not enough,” “This is fresh papaya juice—is very good after long journeys.”

I tried to eat slowly, responding to questions and asking a few of my own, but the delicious dishes occupied most of my attention. Then came dessert—some decadent concoction of grated coconut, pureed mangoes, and caramelized sugar. I attempted to limit my intake, but Beatrice would have none of my gustatory modesty. As soon as I’d finished she gently removed my plate with a smile and returned with an even larger second helping, plus a glass of sweet

chichi

blended from rice and milk, and a slab of cheese made every day at the Estradas’ small dairy from “tame-cow” milk.

“You like?” asked Hugo, eyes twinkling again.

“I like very much. I’m glad I came.”

The family nodded approval.

“Tomorrow, if you wish, you can take a horse early in the morning. The birds are beautiful then,” said Hugo.

“Sounds like a great idea.”

“Good. Five-thirty is a good time. One of the men will bring your horse.”

We talked about the wildlife and Hugo Estrada’s plans to keep most of his ranch in a natural state.

“The other ranchers—we are not always agreeing on matters. Some want to begin cultivation and keep all the cattle tame for cheese and meat. They use chemicals for spraying. They burn their land. They say it makes better grass for the cattle. But when they burn they destroy the places for the birds. Many animals die. It is not good for the Llanos. This is a special place in Venezuela. In the world.”

Beatrice brought me a book the family keeps in which guests at the lodge had described their feelings about Hato La Trinidad.

I read:

I love this land—the land of the Llanero who needs only a knife, a horse, a hammock and a fishing line….

Strong yet gentle—the land and the people.

I toast to the Estradas—a family working hard to keep a balance between man, his enterprises, and nature! The preservation of God’s creation.

One comment referred to Doña Barbara:

Do you represent the dark side of the Llanos—the jaguar, the piranha, the stingray, the electric eel?…perhaps you practiced both good and evil witchcraft for you have surely left us a strange and enchanted land.

Much later I thankfully tumbled into bed to rest before an early start to my “enchanted land” explorations.

By six I was out on the plains—just me and my sleepy horse. The sun rose slowly over the gallery forests by the river, flecking the araguaney trees, jasmines, and acacias with silver-gold light. From the lower trunk of one of the araguaneys grew two exotic rosa de la montana flowers—fiery balls of bright red—glowing like miniature suns. Over in the ranch house palms I heard the resident colony of buff-necked ibis beginning their morning litany of shrieks and scratchy caws. Nearby at the stables the

llaneros—

the “midnight cowboys” of the ranch—were unsaddling their horses after a long night of rounding up the cattle. Way off in the distance I heard the eerie calls of howler monkeys.

At the edge of the

mata

I disturbed a cluster of parrots. They scattered like litter in a hurricane, a hyped-up half-flight of flailing green wings and frantic screeches. Whatever hope I had of quietly photographing the storks and herons by the watering holes was gone. Two five-foot-high jaribu storks rose up in slow laborious flaps from their sentry positions overlooking the half-dry ponds, followed by dainty lines of snowy egrets, white ibis, three whistling herons, and a single scarlet ibis like a flash of red flame. Only the spoonbills remained, trailing the shallows with their strange scooping beaks. Oh, and a macaw too. He sat with his enormous bill, way up in a palm, knowing he was safe and wondering what all the fuss was about anyway.

Something brown and big moved through the sawgrass on the far side of the water hole—maybe a capybara, over three feet high, the largest rodent in the world. A shadowy undulating mass of black closer in turned out to be a bunch of vultures feasting on the remains of fish left behind by the storks and herons. Obviously food was more important to them than fear of an unexpected intruder.

I moved on as slowly and silently as I could across the lightening plain. My horse seemed pleased not to be called upon to gallop. Galloping is not a forte of mine. A lazy saunter suits me much better and it seemed an appropriate pace for such a lovely early morning.

The plain stretched out to misty horizons in all directions. I tried to imagine what it must look like in the rainy season—a vast, seemingly endless lake, sparkling under a hot sun or black as pitch as storms lash its surface. So big. So splendidly remote and untamed.

I could ride for days across this land and see nothing but the plain. No village, no houses, no signs of man’s existence here. Just the breezes, the occasional flurry of birds by a waterhole or over a

mata

; possibly the fleeting shadow of a jaguar…nothing more. Boundless space under a vast blue sky….

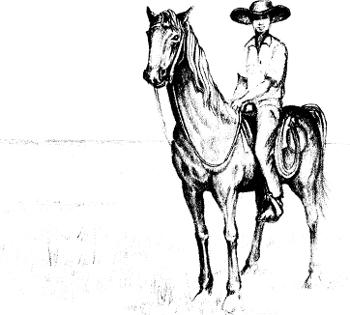

I envied the

llaneros

their freedom. They live their own lives as they have done for generations, hunting the wild steers under the midnight stars, singing their songs of love and lust for this vast tempting plain. Simple, uneducated men, but wise in the ways of this “strange and enchanted” land. Their land.

Which for a while felt to be my land too. I knew so little of its secrets and its dangers, yet I could sense its power in these huge empty horizons. A power that seeemed to pour into me as I rode into the morning light, making me proud to be here and, for a while, proud just to be me, needing nothing.

Much later on, after lunch, I was introduced to José, one of the supervisors of the

hato

’s workers and cowboy

-llaneros

. I wanted to know more—much more—about the life of the

llaneros

and to understand the Doña Barbara legend.

José was middle-aged, with a sinewy body and a sun-burnished face, wrinkled like worn leather. He spoke good English and seemed to enjoy nothing more than sitting in the shade of a palm near the lodge, telling me tales of his heritage and his homeland.

“What was that phrase again?”

“‘Horse first and woman later.’ The old

llaneros

used to say it always. They said many true things. Like the hares of the dawn. Do you know what they are?”

“No.”

He smiled. “They are those little round clouds on the horizon. Pink and then gold in the sunrise. You see them most days.”

“Tell me some more.”

“You maybe think

llaneros

are just ignorant cowboys.” He didn’t wait for my rebuff. “Well—it’s true. Education, schools, big-city things are not very important here. They used to call this ‘the kingdom of the

cimarrones

’—the wild ones. When the Spaniards were here in the 1700s they sometimes would give convicts a choice of imprisonment in the dungeons or deportation to the Llanos. Escaped slaves—they were brought from the Caribbean islands—came here too. So you can imagine what a wild place this was.

Llaneros primitovos

they called us. No one trusted us and we trusted no one. Life was simple. Cabins of adobe and thatch. Hammocks for sleeping. A palisade fence to keep out the wild cattle and the jaguars. Storerooms for cassavas, beans, and corn; a smokehouse where salted meat dried; stables, pigsties, a place for the rope cutter, and a big calabash shade tree by the poultry yard. Sometimes a dairy near the corral for the tame cows and a room for making cheeses from the milk. That was all. Simple.”

“In some ways it doesn’t seem too different today,” I said. “I know there are trucks and bikes—there’s Hugo’s plane—but things are still pretty basic. The

llaneros

seem to live—”

“The

llaneros

!” He grinned. “We’ll never change. We’re still the same as before. We do not make friends easily. We are suspicious of people—even people we know. That is our history. We still don’t trust laws and lawyers. We trust only the knife and the gun and the ‘red glory of death.’ We learned that from Pancha Vazquez—or maybe she learned it from us!”

“Who’s Pancha Vazquez?”

“The one you call Doña Barbara. We called her other names.”

“So I’ve heard.”

“Ah—don’t laugh. Maybe some of the stories were a little—how you say—‘blown up,’ but Pancha had powers. Real powers.”

“Such as?”

“Well—they say she ‘pocketed’ men. She knew the secrets of Camajay-Minare, the black god of the Orinoco. She learned from the Indian women how to make special things from herbs and roots. She gave the men love potions and then did what she liked with them. When she was finished, she—or maybe the wizard, the ‘partner’—got rid of them. That woman had her own cemetery! She had all the secrets from the Indians—the Evil-Eyed, the Breathers, the Prayers. She became very rich. She buried pots—big clay jars—full of twenty-dollar gold pieces. People think they’re still here. They dig for them. They even dug in her grave. They found nothing. No gold. No bones. Nothing.”

“Maybe she was bluffing. Life must have been hard for her here.”

“Hard! Sure it was hard. It was hard for everyone. But she was tough. She could lasso a bull out in the open as well as any peon. She could fight the Cunaviche rustlers and win. She could beat the best lawyers in Caracas—they called Llanos law the law of Doña Barbara. She knew where—which

matas—

the bulls and their herds would hide in when she took the men out at night to tame the cattle and bring them back to the dairy. Many horses were torn to pieces under her by those bulls, but she got away, mounted a spare, and brought them back to the

hato

.”

He looked at me warily to see if I still believed him and nodded when I nodded.