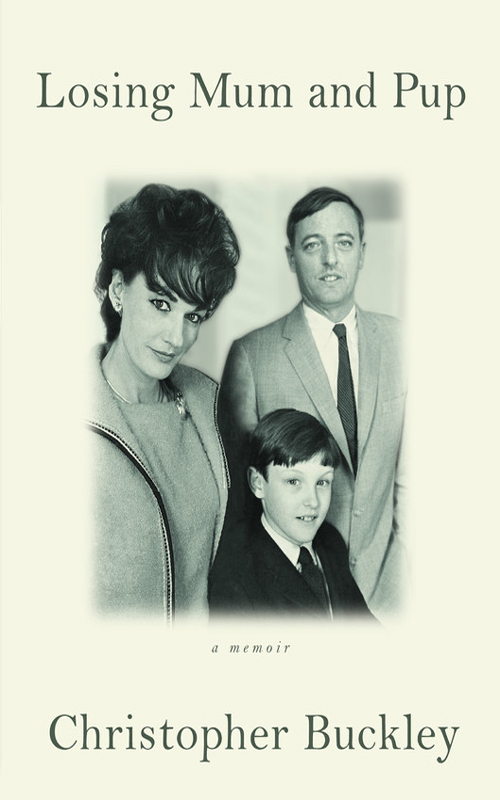

Losing Mum and Pup

Read Losing Mum and Pup Online

Authors: Christopher Buckley

Copyright © 2009 by Christopher Taylor Buckley

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Twelve

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

www.twitter.com/grandcentralpub

Twelve is an imprint of Grand Central Publishing.

The Twelve name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: May 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-55664-4

Contents

CHAPTER 1: April Is the Cruelest Month

CHAPTER 2: She’s Already in Heaven

CHAPTER 3: I Guess We Can Do Anything We Want To

CHAPTER 4: That Sounded Like a Fun Dinner

CHAPTER 5: I Don’t Want Champagne

CHAPTER 6: Dude, What’s With Your Dad?

CHAPTER 7: You Need to Get Here as Quickly as You Can

CHAPTER 8: We’re Terribly Late as It Is

CHAPTER 9: I Miss My Urine Report

CHAPTER 10: You Can Imagine How Pleased Your Mother Was

CHAPTER 11: My Old Man and the Sea*

CHAPTER 12: If It Weren’t for the Religious Aspect

CHAPTER 13: I’d Do the Same for You

CHAPTER 14: Please Not to Arrest My Dear Father

CHAPTER 15: Blood of the Fathers

CHAPTER 16: That Would Be a Real Bore

CHAPTER 17: Boy, How He’d Have Loved This

CHAPTER 18: He’s Looking Much Better

CHAPTER 19: Something I’ve Written for the Paper

CHAPTER 20: A Bit Much to Spring on a Lad with a Morning Head

CHAPTER 21: There’s a Mr. X, Apparently

CHAPTER 22: Home Is the Sailor

CHAPTER 24: The Hunter Home from the Hill

ALSO BY

Christopher Buckley

Supreme Courtship

Boomsday

Florence of Arabia

No Way to Treat a First Lady

Washington Schlepped Here: Walking in the Nation’s Capital

Little Green Men

God Is My Broker

Wry Martinis

Thank You for Smoking

Wet Work

Campion

The White House Mess

Steaming to Bamboola: The World of a Tramp Freighter

for

Julian Booth

Frances Bronson

Danny Merritt

With love and gratitude

LADY BRACKNELL

:… Are your parents living?

JACK

: I have lost both my parents.

LADY BRACKNELL

: Both?… To lose one parent, Mr. Worthing, may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.

—Oscar Wilde,

The Importance of Being Earnest

I have put in italics conversations of whose accuracy I am reasonably confident, and within quotation marks those of whose

accuracy I am entirely confident.

You’re Next

I

’m not sure how this book will turn out. I mostly write novels, and I’ve found, having written half a dozen, that if you’re

lucky, the ending turns out a surprise and you wind up with something you hadn’t anticipated in the outline. I suppose it’s

a process of outsmarting yourself (not especially hard in my case). Perhaps I’m outsmarting myself by writing this book at

all. I’d pretty much resolved

not

to write a book about my famous parents. But I’m a writer, for better or worse, and when the universe hands you material

like this, not writing about it seems either a waste or a conscious act of evasion.

By “material like this,” I mean losing both your parents within a year. If that sounds callous or cavalier, it’s not meant

to be. My sins are manifold and blushful, but callousness and arrogance are not among them (at least, I hope not). The cliché

is that a writer’s life is his capital, and I find myself, as the funereal dust settles and the flowers dry, wanting—needing,

perhaps more accurately—to try to make sense of it and put the year to rest, as I did my parents. Invariably, one seeks to

move on. A book is labor, and as Pup taught me from a very early age—so early, indeed, that I didn’t have the foggiest idea

what he was talking about—“Industry is the enemy of melancholy.” Now I get it.

There’s this, too: My parents were not—with all respect to every other set of son-and-daughter-loving, wonderful parents in

the wide, wide world—your average mom and dad. They were William F. Buckley Jr. and Patricia Taylor Buckley, both of them—and

I hereby promise that this will be the only time I deploy this particular cliché—larger-than-life people. A gross understatement

in their case. I wonder, having typed that: Is it name-dropping when they’re your own parents?

But larger than life they both were, and then some. Larger than death, too, to judge from the public out-pouring and from

the tears of the people who loved them and mourn them and miss them, none more than their son, even if at times I was tempted

to pack them off to earlier graves. Larger-than-life people create larger-than-life dramas.

To the extent this story has a larger-than-personal dimension, it is an account of becoming an orphan. I realize that “orphan”

sounds like an overdramatic term for becoming parentless at age fifty-five; but I was struck by the number of times the word

occurred in the eight hundred condolence letters I received after my father died. I hadn’t thought of myself as an “orphan”

until about the sixth or seventh letter:

Now you’re an orphan…. I know the pain myself of being an orphan…. You must feel so lonely, being an orphan…. When I became

an orphan it felt like the earth dropping out from under me

. At length a certain

froideur

encroached as the thought formed,

So, you’re an orphan now.

I was jolted happily out of my thousand-yard stare a month later by an e-mail from my old pal Leon Wieseltier, to whom I’d

written to say that I was finally headed off to Arizona for some R&R: “May your orphanhood be tanned.”

Orphanhood was a condition I had associated with news stories of disasters; a theme I had examined intellectually in literature

at college and beyond. It’s one of the biggies, running through most of Melville, among others, and right down the middle

of the great American novel

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

.

I’m an only child, albeit encompassed and generously loved by an abundance of relatives, forty-nine first cousins on the Buckley

side alone. Still, I have no sibling with whom to share my orphanhood, so perhaps the experience is more acutely felt. Only

children often have more intense, or at least more tightly focused, relationships with their parents than children of larger

families. This was, at any rate, my experience.

I don’t know that I have anything particularly useful, much less profound, to impart about the business of losing one’s parents,

other than this account of how it went in my case. I doubt you’ll be stunned to hear that it has a somewhat dampening effect

on one’s general felicity and inclination to humor. I recall, on entering the vestibule of Leo P. Gallagher & Son Funeral

Home the first time after Mum died, seeing a table stacked with pamphlets with titles like

Losing a Loved One

or

The Grieving Process,

illustrated with flowers and celestial sunbeams. As a satirist, which is to say someone who makes raspberries at the cosmos,

my inclination is to parody:

Okay, They’re Dead: Deal with It

or

Why It’s Going to Cost You $7,000 to Cremate Mummy.

But standing there with my grief-stricken father, the banal suddenly didn’t seem quite so silly or in need of a kick in the

rear end, and (believe me) I’m a veteran chortler over Oscar Wilde’s line “It would require a heart of stone not to laugh

at the death of Little Nell.” Right after JFK was shot, Mary McGrory said to Daniel Patrick Moynihan, “We’ll never laugh again,”

to which Moynihan responded, “Mary, we’ll laugh again, but we’ll never be young again.”

It occurs to me that Moynihan’s reply brushes up against the nut of the orphanhood thing (as my former boss George H. W. Bush

might put it)—namely, the accompanying realization that

you’re next

. With the death of the second parent, one steps—or is not-so-gently nudged—across the threshold into the Green Room to the

river Styx.

One of my early memories, age five, is of being in bed with my parents and being awoken in the middle of the night by the

ringing of the phone. A great commotion of grown-ups followed: Mum going down to make coffee, Pup hunched over the phone,

speaking in grave, urgent tones. Of course, I found it all exciting and eventful and hoped it would involve—with any luck—a

reprieve from school that day. “What is it?” I asked Mum. “Pup’s father has died, darling.” Apart from being in the car when

she drove over the family cocker spaniel, this was my first brush with death. Then, an even half century later, the phone

rang again with the news that my father had died.

In the Zen koan, the noble lord sends word throughout the land, offering a huge reward to anyone who can distill for him in

poetry the definition of happiness. (This was in the days before

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?

) A monk duly shuffled in and handed the nobleman a poem that read, in its entirety:

Grandfather dies

Father dies

Son dies.

His Lordship, having had in mind something a bit more, shall we say, upbeat, unsheathes his sword and is about to lop off

the head of the impertinent divine. The monk says (in words to this effect),

Dude, chill! This

is

the definition of perfect happiness—that no father should outlive his son.

At this, His Lordship nods—or, more probably, after the fashion of Kurosawa’s sixteenth-century warlords, grunts emphatically—and

hands the monk a sack of gold. I’m sure the story reads more inspiringly in the original medieval Japanese, brush-painted

on a silk scroll, but it’s a nifty story, even as I now confront the fact that I have moved to the bottom line. My son, William

Conor Buckley, whose namesake grandfather died on the morning of his sixteenth birthday, now himself moves one step closer

to the Stygian Green Room, but if the old Zen monk’s formula holds, he won’t beat me to the river. Or so I, a heathen, fervently

pray.

Many of those kind letters I received echoed another apparently universal aspect about parental mortality— namely, that no

matter how much you prepare for the moment, when it comes, it comes at you hot, hard, and unrehearsed. Both my parents had

been ill and suffering, so when the end came to each, it was technically a blessing. And yet there you stand in room 2 of

the Stamford Hospital critical care unit, having just calmly given the order to remove the breathing tube, sobbing uncontrollably—sobbing,

as distinct from crying or weeping—even though you spent eight hours in a car driving toward this scene, knowing pretty much

what to expect. Then, ten months later, cradling the phone and wandering foggily and aimlessly about the house, wondering,

almost like an actor trying to figure out how to play the scene:

Okay, you’ve just gotten word that your father is dead. You… let’s see… punch the wall, shout, “Why? Why?”—

not quite knowing what to do, or say, or what gesture is called for. Something, surely? Before getting the call, I’d been

on the way to my little study out back to do my income taxes. (Death and taxes, all in the same day. One reverts to childhood:

Go hide. Maybe they won’t find you.

In the end, I just leaned my forehead against the inside of the front door, took in a few breaths, then walked upstairs to

man the phones, which I knew would soon start to ring.