Lords of the Sky: Fighter Pilots and Air Combat, From the Red Baron to the F-16 (18 page)

Read Lords of the Sky: Fighter Pilots and Air Combat, From the Red Baron to the F-16 Online

Authors: Dan Hampton

Tags: #History, #United States, #General, #Military, #Aviation, #21st Century

Real dogfighting ended on November 4 as the German retreat became a complete rout in most places. Valenciennes had fallen on November 2, and Le Quesnoy, Landrecies, and the Mormal Wood were now all in Allied hands. Riots had broken out in earnest in Berlin, and the flu epidemic continued.

*

The German High Seas Fleet had even mutinied after being ordered out to fight.

The next several days saw back-and-forth confusion exacerbated by bad communications and poor leadership on both sides. Kaiser Wilhelm officially abdicated and fled for the Netherlands on November 10, so a German delegation asked for terms. The reply stated that the Germans had to evacuate Belgium, Luxembourg, Alsace-Lorraine, and France within fifteen days. Additionally, the initial armistice terms demanded the withdrawal of all troops inside Germany to a point 25 miles east of the Rhine, and all Allied prisoners were to be repatriated. Artillery, tanks, machine guns, and nearly all other weapons of war were to be handed over to the Allies. The Luftstreitkräfte would assemble at Strasbourg, and all aircraft were to be surrendered to a French commission. As of 11:00 a.m. on Monday, November 11, 1918, the war was over.

Haggard German regiments began marching west over the Rhine bridges on November 14, bound for home. Sometimes a band would play “Fridericus Rex” or the “Torgauer Marsch,” and by December 11, the Döberitz Guards were stomping down the Unter den Linden in Berlin. Friedrich Ebert, who would serve as the new president of Germany, presented a “victory” to the people. After all, it was an armistice, not a surrender. “We welcome you home,” he shouted from a flower-covered podium under a clear blue sky. “No enemy has defeated you.”

Nevertheless, the armistice terms were harsh, and those coming from the 1919 Treaty of Versailles would be worse. The victors wanted Germany to suffer—understandable, given that the war had cost some 30 million dead, wounded, and missing.

*

Some cities in America banned Beethoven and the Strauss waltzes; others forbade speaking in German, and in Cincinnati a priest was beaten because he’d prayed for the Kaiser’s soul. The French spit on passing Germans.

In the meantime, the survivors came home and picked up the pieces as best they could. The old order of things was gone, and they tried to make their way in the new. England and France both persevered and recovered, but the empires of Austria-Hungary, tsarist Russia, and Ottoman Turkey vanished forever. Germany, like its allies, descended into chaos for a time, yet would eventually emerge bitter and vengeful.

For the pilots it was now a world that included aviation on a scale unimagined five years before. Ernst Udet and many others would become barnstormers and stunt flyers. Lothar von Richthofen and Eddie Rickenbacker were among those who joined fledging air carrier operations. Other pilots, disillusioned or simply bored, would follow the war drums into lesser-known but equally deadly conflicts in Russia, Poland, and Spain.

A terrible price had been paid by all. Men had burned, bled, and fallen to horrible deaths. The Royal Air Force alone suffered a 15 percent casualty rate, with some 16,500 airmen killed, wounded, or missing. Despite such horrifying losses, by 1918 the RAF was 114,000 strong and could field more than four thousand combat aircraft—this after a start of barely 2,000 men with a few dozen mismatched, unarmed machines in 1914. Other nations had seen similar explosive growth.

The end of the war brought a widespread desire to put away the weapons and cut back the armies. After all, it had been the “war to end all wars,” and the enemy was vanquished, so the victors wanted to live and celebrate. Unfortunately, as with most illusions, this one was dangerous and would have dire consequences for the future.

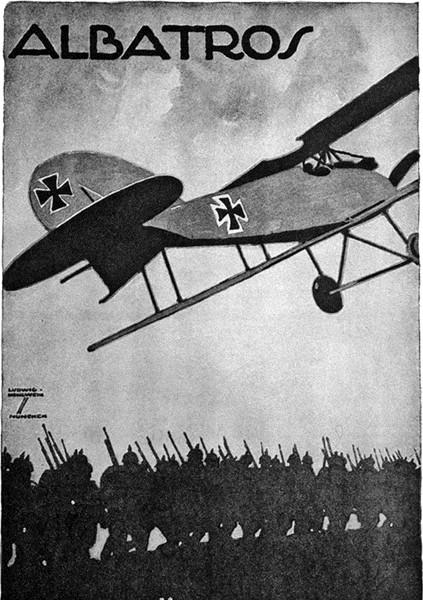

While the Great War settled into a brutal stalemate on the ground, combat aviation evolved rapidly, developing from zeppelins and unarmed reconnaissance planes to increasingly sophisticated—and deadly—fighter aircraft. This poster celebrates the German Albatros, which the Allied Powers struggled to match.

Legendary English ace Albert Ball, VC. At the time of this death at age twenty, Ball was Britain’s top ace—and a romantic hero back home.

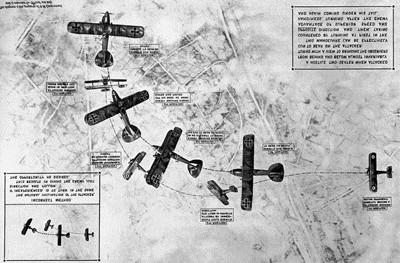

A diagram of proper World War I fighter attack maneuvers.

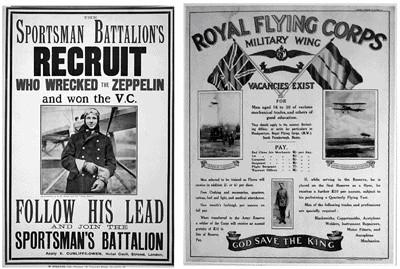

British recruiting posters.

(Library of Congress)

Edward “Mick” Mannock, Britain’s leading ace, with 61 victories.

“The Eyes of the Army”: the iconic Sopwith Camel.

(The British Museum)

A postcard celebrating the fortieth victory by German ace Oswald Boelcke, the father of combat aviation tactics.

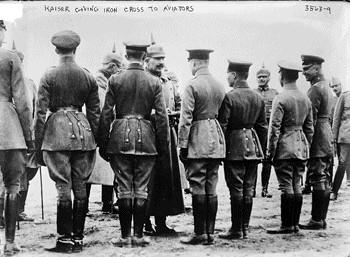

Kaiser Wilhelm II “giving [the] Iron Cross to aviators.” The Prussian military quickly incorporated pilots into their traditions.

(Library of Congress)