Long Way Home

Authors: Bill Barich

Long Way Home

Â

ON THE TRAIL OF STEINBECK'S AMERICA

Bill Barich

For Imelda

Once more with love

“We do not take a trip; a trip takes us.”

â

JOHN STEINBECK

Part One

Â

W

HEN I WAS

in my late teens and hungry for the road, ready to sign on as an angelheaded hipster if only I knew how or where, I bought a copy of John Steinbeck's

Travels with Charley

and whipped through it in a couple of days. The idea of rambling around America carefree and independent, with no particular destination in mind, appealed to my deepest fantasies. Like Steinbeck, I'd drink applejack with fruit pickers, tour the Badlands, and crest the Rockies, perfectly content to survive on cowboy coffee and corned-beef hash and sleep by a fast-flowing stream.

That never happened, of course. More than forty years went by before

Travels

entered my life again when I stumbled on an old paperback edition at a thrift shop in Dublin. The cover illustration showed a rugged-looking Steinbeck sitting on a grassy hillside next to a French poodle tinted an odd shade of purple. In the distance, you can see the camper he called Rocinante after Don Quixote's horse, along with a vineyard and some mountains that resemble the Gabilans near his birthplace in Salinas, California.

“The #1 National Bestseller Now Only 75 Cents,” cried a banner over the title. I paid two euros myself, eager to share Steinbeck's adventures again after almost a decade in Ireland, but the book let me down. It bore no relation to my youthful memory of it, except for the affectionate portrait of Charley. The colorful characters I'd enjoyed seemed cut from cardboard, and their dialogue sounded wooden.

Travels

was melancholy rather than merry, steeped in loneliness and fatigue.

Puzzled, I consulted a biography of Steinbeck and a volume of his letters. He'd deliberately intended to distract his readers, I discovered. His wit and warmth were manufactured, a product of his skillful sleight of hand, or so he confided to his editor, Pascal Covici. At the core of

Travels

is a bleak vision of America's decline that he chose to mitigate by telling jokes and anecdotes.

In reality, the United States suffered from “a sickness, a kind of wasting disease,” he warned Covici in private, and Americans, overly invested in material toys and saddled with debt, were bored, anguished, discontented, and no longer capable of the heroism that had rescued them from the terrifying poverty of the Depression.

“And underneath it all building energies like gasses in a corpse,” he mourned. “When that explodes, I tremble to think what will be the result.”

His words had the ring of prophecy when I came across them in August 2008. With the economy in free fall, it appeared as if the gasses had exploded, leaving the survivors to wander haphazardly through the aftermath with no leadership or sense of direction. That was the impression the media created, at any rate, but I couldn't vouch for its accuracy. I had lost touch with my own country during my time abroad, the same reason Steinbeck gave for taking his trip.

He'd been living in New York and England and felt cut off from his subject matter, so he devised a plan to explore the heartland and refresh himself. He once referred to it as Operation Windmills, another reference to its quixotic essence. In September 1960, right after Labor Day, he'd set out from his home in Sag Harbor, the historic whaling village on Long Island, to rediscover America. Initially, his morale was high.

“I'll avoid cities and hit small towns and farms and ranches, sit in bars and hamburger stands and on Sunday go to church,” he enthused to some friends. “I am very excited about this. It will be a kind of rebirth.”

For a man of fifty-eight, the wish to be reborn suggests a deep unrest, and that was true of Steinbeck. He was more frank with his agent, Elizabeth Otis, dropping the jolly pretense as his departure drew near.

“Between usâwhat I am proposing is no little trip or reporting,” he admitted, “but a frantic last attempt to save my life and the integrity of my creative pulse.”

According to his biographer Jay Parini, he was depressed, spiritually adrift, and fearful his best work had all been done. His health was fragile, too. Normally robust, he'd been rattled by a pair of minor strokes that were never properly diagnosed, his wife, Elaine, said. Already the dark thoughts were brewing, but Steinbeck tried valiantly to conquer them. As Americans will do, he looked to the road for a cure.

In spite of its flaws,

Travels

ignited my old fantasies, and I began to think about making a similar trip almost half a century later. As a voluntarily displaced Californian, I understood Steinbeck's craving for some contact with the heartland. Along with rediscovering America myself, I could put his prophecy to the test. If the nation hovered on the edge of ruin, I'd record it faithfully, but I hoped to prove him wrong. In an election year, with the fabled winds of change trying hard to blow, the future was up for grabs.

Steinbeck spent about eleven weeks on the road, while I'd have to settle for six on a tight budget. I considered renting a camper, naturally, but the cost proved astronomical, especially after I factored in the soaring price of gas, so I'd go by car instead and swallow the bitter pill of motel living. In fact, Elizabeth Otis had advised her client to do the same, concerned that Rocinante would isolate him from others and compromise his intention.

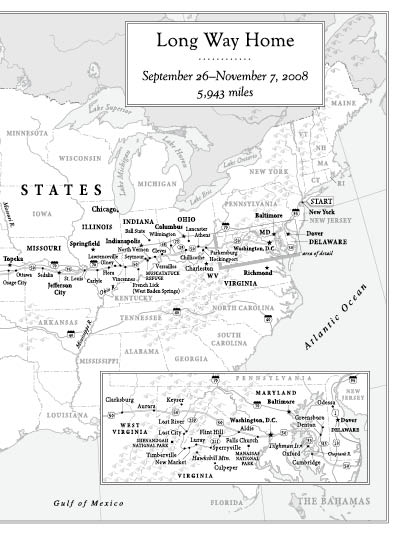

For my primary route from coast to coast, I settled on U.S. 50. The highway, lightly traveled in many stretches, runs for about thirty-two hundred miles from Maryland to the Pacific through the middle of America. The back roads would grant me access to plenty of small townsâCoolville, Ohio, say, or Peabody, Kansasâas well as farms and hamburger stands. There'd be no shortage of churches, either. When I saw that Chesapeake Bay, the Missouri River, the Santa Fe Trail, and the Great Basin Desert were all on my itinerary, I nearly broke into a ballad from the Pete Seeger songbook.

With those decisions made, I had just one more issue to address. What about a dog to act as Charley's stand-in? I must have fielded the question fifty times at least. Most people were jokingâI don't have a dogâbut a few diehard literalists meant business. One woman even offered to loan me her hairless terrier Beanie, an amusing little guy who wears clothes outdoors to protect his sensitive skin from the sun.

As much as I appreciated her generosity, the chance to play valet to a terrier over thirty-two hundred miles struck me as absolutely no fun. Although I'd seized on Steinbeck as a model and an inspirationâI explained this to the kind womanâI did not feel compelled to duplicate his trip in every detail, a dull exercise in comparing and contrasting. What intrigued me was the relative validity of his prophecy.

Travels with Beanie

? No way. I'd go it alone.

IN EARLY SEPTEMBER,

I booked a ticket to New York on Aer Lingus and a humble Ford Focus with Budget Rent A Car at JFK. For my first night's lodging, I reserved a motel room in Dover, Delaware, perilously close to a harness track and casino I'd already begun to steel myself against. If I hoped to be in San Francisco in time for the presidential election, I'd have to be steadfast. A taste for low entertainment has derailed many an expedition, after all.

A trip spawns advisers in schools, Steinbeck observed, and he was dead right. Without having to ask, I collected tips on hot springs, fishing holes, scenic drives, geological oddities, topless bars, and obscure museums devoted to eccentric pursuits. There were roadside attractions I dared not missâthe UFO Watchtower in Hooper, Colorado, say, just a fifty-two-mile detour from U.S. 50. My pals recommended both fine restaurants and greasy spoons, including the best spots for five-way chili around Cincinnati.

Avoid Indiana on a Sunday, someone counseled me. It's against the law to buy any beer to take home.

On my own, I tried to get up to speed on the America I'd left behind. At times I felt baffled as I trawled the Internet, reading about TiVo digital recorders and Kobayashi, the hot dog eating champ.

American Idol

had passed me by entirely, although for that I was grateful. I'd never visited at an Applebee's, either, where about two million of my fellow citizens chow down every day, nor had I seen a Prius, shopped at Costco, or watched a cage fight. I'd been deprived. Or maybe spared.

In my rare moments of anxiety, which I hated with a passion and refused to ascribe to advancing age, I wondered if Steinbeck's “monster land” would overwhelm me just as it did him. The country he went searching for, a figment based on his nostalgic childhood memories, scarcely existed anymore. The open space of his beloved San Joaquin Valley was rapidly disappearing, for instance. About 1.5 million farms in the United States had gone under since 1950.

Our cities also had been transformed beyond recognition. Of the fifteen largest metro areas, only Los Angeles had gained rather than lost residents over the same period of time. By 1960, Americans had decamped to the suburbs, and one in every four families occupied a house that had been built in the previous decade.

They were in hock to the banks now for their mortgages, auto loans, and such material toys as a television set. Eighty-eight percent of all households owned a TV, as opposed to just 11 percent in the 1950 census. In exchange for their comforts, though, they'd sacrificed a degree of independence. They labored, more and more, for corporations, while the ranks of blue-collar workers and the self-employed were at an all-time low.

For Steinbeck, a self-reliant type, it must have been galling to see the soft underbelly of the nation exposed.

“Over and over I thought we lack the pressures that make men strong and the anguish that makes men great,” he griped to Pascal Covici.

He longed for the America of his youth, I believe, and the integrity of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whose values he shared. In his inaugural address of March 1933, Roosevelt had the audacity to urge his often destitute constituents to keep their financial losses in perspective. A plague of locusts hadn't descended on them, he chided, nor had they endured the hardships of the forefathers.

“Our common difficulties concern, thank God, only material things,” FDR intoned. Happiness doesn't lie in the mere possession of money, he added. It lies instead in the joy of achievement and the thrill of creative effort. The unscrupulous money changers “have no vision, and when there is no vision the people perish.”

Roosevelt's speech captured the excellence Americans once aspired to, so I packed a copy for my traveling library. FDR joined such old favorites as Emerson, Thoreau, and Melville, but I gave Walt Whitman a break, figuring he must be tired after riding shotgun with so many pilgrims before me. I brought along some Henry Miller, too, and also Sinclair Lewis's George F. Babbitt, who'd have been knee-deep in the subprime mortgage scandal.

“He made nothing in particular, neither butter nor shoes nor poetry,” said Lewis, “but he was nimble in the calling of selling houses for more than people could afford to pay for them.”

Steinbeck loaded his camper with tons of junk he never usedâpadded subzero underwear, for exampleâso I stuck to the basics. I took a flyrod, a sleeping bag, some hiking boots, binoculars, and a first-aid kit, as well as my laptop, a cell phone, notebooks, and a thick Rand McNally road atlas. Though Steinbeck stocked enough booze to float a fraternity party, I knew the treachery of lonely nights in one-horse towns and exercised caution in that regard.

IF I HAD

any doubts about the universal appeal of a road trip, the cabbie who drove me to the Dublin airport put them to rest. When he heard my accent, he regaled me with an account of his recent family holiday at Disney World in Orlando, where the “actual amount of sunshine”âhis very wordsâstunned him and, needless to say, burned him to a crisp. He sighed and wished he could go with me, although that would mean deserting the wife and kids in Ballybrack.

“In a big Cadillac convertible, that'd be the way to do it,” he chirped. I didn't have the heart to puncture his daydream by mentioning the Focus.

In New York, my cabbie wore a turban and spoke not at all. He dropped me on the Upper West Side, where I'd stay with friends for a brief while before picking up the car. After the dismal news reports, I expected to see evidence of the apocalypse in the streets, but the miracle of everyday life still went on. The mailman completed his rounds, a little girl fell off her bike and skinned a knee, a furtive couple slipped into a seedy hotel, and so on. I found this somehow comforting.

In sunny Central Park, the ice-cream vendors were doing just fine despite the plunging value of 401(k)s. My friends opened a bottle of wine, and we moved to a terrace and watched dozens of joggers circle the reservoir, trying to outrun any phantoms pursuing them. The talk was of politics, not economics, and how Sarah Palin had lately been meeting with world leaders, among them Asif Ali Zardari, Pakistan's flirtatious new president, who called her “gorgeous.”

In

Travels

, Steinbeck used the Spanish term

vacilando

to describe a peculiar kind of wandering. “If one is vacilando, he is going somewhere but doesn't greatly care whether or not he gets there, although he has direction.”

I became an expert

vacilador

in Manhattan, visiting museums and galleries and treating myself to lunch at the Grand Central Oyster Bar, where every table was occupied. Shoppers were still splurging on Pescatore's lobster at the station's market, too, and Queso del Tietar from Murray's Cheese at thirty bucks a pound. The prime aged beef at Gallagher's nearby, displayed in all its marbled splendor, had lost none of its allure.

Maybe New Yorkers were in denial, but that was true only in the bastions of privilege. A long line of youths, mostly African American and Hispanic, stood outside a Circuit City on Broadway one morning, clutching their résumés beneath a “Now Hiring” banner. The lucky few to land a job would lose it a few months later when Circuit City went belly-up, a symptom of the nation's woes.