London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City (18 page)

Read London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City Online

Authors: Drew D. Gray

In 1957, Michael Young and Peter Willmott published their seminal study of families and family life in London.13R They chose to focus on the East End and in a challenge to contemporary notions of the `nuclear' family they uncovered a world in which community and family retained very strong ties with the streets and geography of the East End. The women of the area who, by implication, could not rely on their men folk to bring up and support their families maintained strong female networks of kinship. As the authors have written: `The extended [East End] family was her trade union, organised in the main by women and for women, its solidarity her protection against being alone'.139 This is, in some ways, how we now view the East End - channelled as it is through the fictional relationships of the inhabitants of Albert Square - as an area in which some essence of community spirit and extended family ties survives. This is a positive view of East London and it sits alongside that other long-held and equally constructed view of the East End as a dangerous playground for the middle-class `slummer', full of exotic foreigners, criminals, prostitutes and downtrodden paupers in need of rescue.

As we have seen in this chapter much of the responsibility for representations of both the ingidenous and immigrant populations of the East End can be laid at the door of the popular press. The so-called `fourth estate' was flexing its muscles in the second half of the nineteenth century and it is arguable that without them the story of the Whitechapel murders and the character of `Jack the Ripper' would be little more than a distant memory. With this in mind we can now look at the actions and attitudes of the Victorian press in greater detail.

4

Read All About It! Ripper News and Sensation

in Victorian Society

nothing can ever get itself accomplished nowadays without sensationalism ... In politics, in social reform, it is indispensable

So spoke the father of investigative journalism, William Stead, in 1886. Stead, as the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, was in the vanguard of the so-called `new journalism' that revolutionized the newspaper industry in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The development of a new and, arguably, `modern' press had much to do with the importation of new technologies from America and a growing literate and relatively affluent population at home. New journalism can be closely linked to sensation literature, crime reporting and other forms of popular culture such as the music hall and melodrama. The newspaper industry was highly competitive in the late nineteenth century, no more so than in London. This competition drove editors to develop new styles of news presentation to attract readers and advertisers to their products and to search for news items that would keep readers interested enough to follow stories for days or weeks on end. In the Whitechapel murders they had an almost ready-made sensation story to report. `Jack' provided them with an ongoing news item that ran for several months and an almost mythological villain who harked back to bogeyman figures from the earlier part of the nineteenth century and beyond.

The spotlight of attention that the Ripper murder threw upon the East End allowed the campaigning element of the press to decry the desperate poverty of the district and issue dire warnings about the state of the nation. The failure of the police to capture the killer similarly enabled some sections of the press to use this as a stick with which to beat the government and the commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. In short the Whitechapel murders facilitated the creation of what Stanley Cohen has identified as a'moral panic' in late Victorian society. In this chapter we will explore the nature and development of the Victorian press and `new journalism, and their relationship to sensationalism and contemporary popular culture. In closing we will consider whether in their reporting of the Whitechapel murders the press were responsible for creating a moral panic in late Victorian London.

THE RISE AND RISE OF THE VICTORIAN PRESS

By the time the Whitechapel murders came to dominate the newsstands of the capital London was served by thirteen morning and nine evening daily newspapers.' In addition Sunday papers and weekly journals provided Londoners with a tremendous variety of news, gossip and stories from the Empire and beyond. By the 1880s newspapers catered for a diverse reading public as literacy rates improved and printing costs fell. It was probably this latter development that allowed the massive increase in newspaper sales in the second half of the century. Newspapers had been around for over 300 years but had not become a fixed part of daily life until the late eighteenth century. Newspapers had cut their teeth in the propaganda battles of the English civil war but were subject to government censorship until 1695. Up until 1700 all newspapers had been printed in London but the new century saw the appearance of papers in major provincial centres such as Norwich and Bristol. Experimentation followed quickly and by 1760 some 130 different papers had been inaugurated (although only 35 managed to stay in business) and 200,000 copies were being printed daily - this figure had doubled by 1800. By the late eighteenth century reading a newspaper was an important part of a gentleman's daily activity.

The 1780s saw weekly, thrice weekly and daily newspapers in circulation and by the early years of the new century the political weekly and the Sunday newspaper had appeared. Growth was dramatic, especially in the provinces. However, the provincial press in the eighteenth century had relatively little that was original on their pages. They took their news from London, steered clear of controversy and filled their columns with advertising. However, increased competition in the 1800s led to some changes in these local papers. These provincial papers began to report local issues and were more prepared to use editorials to voice concerns and make political statements. This in turn led to the emergence of some of the more important, and in some cases more radical, papers such as The Manchester Guardian.

By 1814 The Times had improved its output by utilizing steam power, and faster production was eventually combined with faster distribution after the advent of the railways. This helped the `respectable' press outstrip and outsell the `pauper' press (organs such as The Black Dwarfwhich catered for a radical middle and working class that demanded electoral reform). The radical press was still effectively muzzled by government interference and restricted in its readership by the high costs of production and by taxation. However, after the failure (or defeat) of Chartism, politicians became more willing to reduce restrictions on the press in the form of stamp duty.

Historians have characterized the press as an agent of social control in the nineteenth century, inculcating accepted norms of behaviour and standardizing opinions about state institutions. Some contemporaries certainly felt the press could have an important role in society; there was a belief, as expressed by men such as Palmerston and Gladstone, that the press could be force for good by bringing the nation closer together. The new police (created by Peel in 1829 and gradually introduced across England and Wales over the next 25 years) believed it could help cut crime. Educators believed it could increase knowledge in a positive way. As Alan Lee concludes, politically, `it was argued, a cheap press was an essential component of an educated democracy'.2 This new confidence in the positive potential influence of print media resulted in tax reform in the 1850s. The duty on advertising was removed in 1853, and this was followed two years later by the exemption of newspapers from stamp duty. Finally production was made cheaper still by the abolition of paper tax in 1861. The result was the birth of a middle-class daily press that was much more affordable to many more consumers. One of the first beneficiaries of this was the Daily Telegraph, which had carved out a circulation of 250,000 by the 1880s. The numbers of newspapers soared - from 795 in 1856 to `well over 2,000 by 1890'.3

Removing taxation and government influence from newspapers was one key factor in the expansion of the `fourth estate' in the nineteenth century but there were other important technological advances in newspaper production that helped extend the reach of journalism during this period. After 1843 the telegraph aided the rapid spread of information and the rotary-action printing machine increased outputs. In 1855 the industry received another injection of technology with the importation of an American invention that relied on rotating type cylinders, the Hoe type revolving machine.4 By the 1890s the linotype had arrived on Fleet Street allowing the production of 200,000 copies of a paper each hour. Such mass production allowed for cheap prices so that the popular newspaper was `securely implanted in to the cultural landscape as an essential reference point in the daily lives of millions of people'.5 The popular press had arrived and would continue to dominate news media until television and eventually the internet challenged its position in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

As Richard Williams has observed, in `the course of the nineteenth century the development of the newspaper from a small-scale capitalist enterprise to the capitalist combines of the 1880s and onwards was at every point crucial to the development of different elements of popular culture" The newspapers brought events like the Ripper murders directly into people's homes, work and leisure places and allowed families to consume the very latest scandals and murders over their breakfast. However, this new development was not universally welcomed and some discordant voices were raised in warning of the consequences of the public appetite for salacious news. One cartoon in Punch from 1849 is indicative of a concern that newspapers could have a negative effect on society.

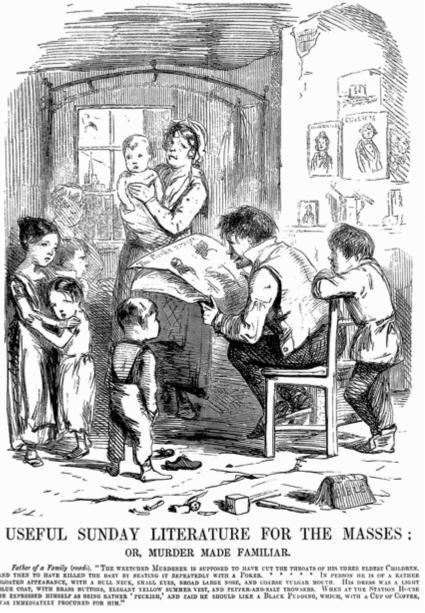

In the cartoon a father reads the newspaper to his wife and family. He recounts the details of a gruesome murder of two children by their father and the rather glib description of the killer and his calm behavior when in custody. The paper is apparently making light of the murder and turning it into entertainment. The walls of the home are covered in images from the popular penny dreadfuls which published the short lives of notorious criminals both past and present; there is little else in the home, which implies that, in the artist's opinion, rather too much of the family's budget is being spent on such dubious reading material. The father's work tools lie scattered on the floor, as does the family Bible. It is a Sunday and the clear implication is that this family should be at church not idling at home reading the penny press.

Figure 3 `Useful Sunday literature for the masses', Punch, September 1849'

By the 1880s the popular press had grown notably by loading its copies with the Sunday papers' traditional mainstay of crime, salacious sensation and gossip. In 1880 Tit-Bits was launched in along with Pearson's Weekly, both of which offered scraps of information, competitions and jokes. In October 1888, as the Whitechapel murders occupied the column inches of most papers, a new periodical was released. Pick Me Up! was launched with the following opening gambit:

We propose to look mainly in the comic side of life ... politics we eschew. We have a notion that the party for the time being uppermost will get along just as well without our assistance. Anyhow they must try.

We don't profess to improve anybody's mind. It takes us all our time to improve ours.

This rather uninspiring publication also carried a poem entitled `One more unfortunate' which alluded to the downfall and disgrace of a young woman who is `hunted' (like a butterfly) and who ends up taking her own life by throwing herself into the Thames by Westminster.' It managed to treat a difficult subject (many prostitutes committed suicide during this period) in a light-hearted way with doggerel verse and crude line drawings. Unlike the more serious papers, publications such as Pick Me Up! were unashamedly dedicated to light entertainment and trivia. However, while the removal of stamp duty and improvements in technology allowed a popular press to develop, there were individuals who still shared the belief with Gladstone and others that the press could be a force for social change and education.

WILLIAM T. STEAD AND THE NEW JOURNALISM OF THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY

While the early nineteenth-century press had sought political influence, that of the second half of the century strove more for profit than political clout. Naturally there were exceptions like The Times that, despite its falling circulation from 1860 onwards, persisted with its sober presentation of the news and steadfastly refused to adopt newfangled editorial devices that might have won it a wider audience. One paper that did choose to innovate was the Pall Mall Gazette. The Gazette had started life in 1865 under the stewardship of Frederick Greenwood as editor and George Murray Smith as owner. However, when Smith gave up control of the paper to his son-in-law, Henry Yates Thompson, in 1880, Greenwood quickly fell out with the new proprietor over politics. For a while the Gazette floundered and Thompson turned to the radical editor of The Northern Echo, a Darlington based local paper, to help improve the Gazette's circulation and profile. It was a bold and astute move. As editor of The Northern Echo William T. Stead had established a reputation for political journalism that had won praise from leading Liberal politicians including Gladstone and Joseph Chamberlain. Within three years of joining the Gazette as assistant editor to John Morley, Stead had made the editorship his own. Over the next few years Stead transformed the fortunes of the paper and delivered a series of hard-hitting editorials and features, the most famous of which - the `Maiden tribute of modern Babylon' - is discussed in Chapter 6.