Living Low Carb (11 page)

Authors: Jonny Bowden

1. Pass it right through and send it into the bloodstream

2. Transform it into glycogen and store it (in the liver or the muscles)

3. Use it to make triglycerides

Remember, as far as your body is concerned, the most important thing is to prevent blood sugar from getting too high. Your insulin may very well be able to keep your blood sugar in the normal range, but the high level of insulin needed to do the job—plus the high levels of triglycerides and VLDLs being created at the same time—are silently laying the foundation for future damage: you are slowly on your way to becoming overweight and/or insulin-resistant.

Insulin Resistance: The Worst Enemy of a Lean Body

Insulin resistance makes losing weight incredibly difficult and is a risk factor for heart disease and diabetes. It is not something you want, and you

can

do something about it. Here’s how insulin resistance develops: the muscle cells don’t want to accept any more sugar (this is especially true if you have been living a sedentary life). They say, “Sorry, pal, we’re full, we don’t need any more, we gave at the office, see ya.” Muscle cells become

resistant

to the effects of insulin. But the fat cells are still listening to insulin’s song. They hear it knocking on their doors, and they say, “Come on in, the water’s fine!” The fat cells fill up and you begin to put on weight.

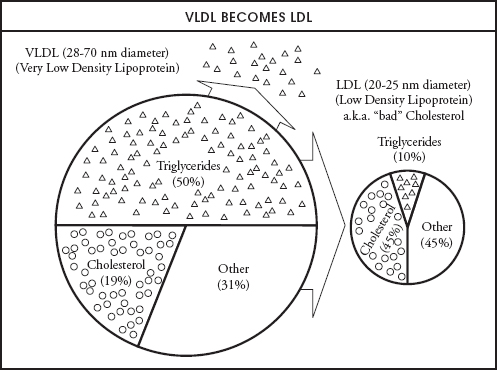

Meanwhile, back in the bloodstream, those little packages called VLDLs that we talked about earlier are carrying triglycerides around trying to dump them. After the VLDL molecules drop off their triglyceride passengers to the tissues and the ever-expanding fat cells, most of them turn into LDL (“bad”) cholesterol.

Now you’re overweight, with high triglycerides, high LDL cholesterol, and

definitely

high levels of insulin, which the pancreas keeps valiantly pumping out in order to get that sugar out of the bloodstream. From here, two scenarios are possible, neither of them good.

In one scenario, your hardworking pancreas will somehow be able to keep up with the workload and keep your blood sugar from getting high enough for you to be classified as diabetic. But you will be paying the price for that with high levels of insulin and the increased risk factors for heart disease that go with them. In the other scenario, your poor pancreas will eventually become exhausted—even its most valiant efforts to shoot enough insulin into the system won’t be adequate for the job. The sugar will run out of places to go, so it will stay in the blood and your blood sugar levels will rise. Now you’ll have elevated insulin

and

elevated blood sugar, plus, of course, high triglycerides and abdominal obesity. If your blood sugar continues to rise even more, beyond the capacity of your insulin to reduce it, you’ll eventually have full-blown type 2 diabetes.

Welcome to fast-food nation.

What’s So Bad about a Little Sugar?

Obviously, the body knows how important it is to protect the tissues, the brain, and the bloodstream from excess sugar. So what exactly does sugar do that’s so damaging to the body that the body is willing to risk the effects of large amounts of insulin and dangerously high levels of triglycerides just to prevent it?

Well, for one thing, excess sugar is sticky (think cotton candy and maple syrup). Proteins, on the other hand, are smooth and slippery (think oysters, which are pure protein). The slippery nature of proteins lets them slide around easily in the cells and do their jobs effectively. But when excess sugar keeps bumping into proteins, the sugar eventually gums up the works and gets stuck to the protein molecules. Such proteins are now said to have become glycated. The glycated proteins are too big and sticky to get through small blood vessels and capillaries, including the small vessels in the kidneys, eyes, and feet, which is why so many diabetics are at risk for kidney disease, vision problems, and amputations of toes, feet, and even legs. The sugar-coated proteins become toxic, make the cell machinery run less efficiently, damage the body, and exhaust the immune system.

4

Scientists gave these sticky proteins the acronym AGES—which stands for

a

dvanced

g

lycolated

e

nd-products—partially because these proteins are so involved in aging the body.

For another thing, high blood sugar is also a risk factor for cancer—cancer cells consume more glucose than normal cells do.

5

Researchers at Harvard Medical School suggested in the early 1990s that high levels of a sugar called galactose, which is released by the digestion of lactose in milk, might damage the ovaries and even lead to ovarian cancer. While further study is necessary to definitively establish this link, Walter Willett, MD—chairman of the Department of Nutrition at the Harvard School of Public Health and one of the most respected researchers in the world—says, “I believe that a positive link between galactose and ovarian cancer shows up too many times to ignore the possibility that it may be harmful.”

6

Sugar depresses the immune system. It makes the blood acidic, and certain white blood cells (lymphocytes) that are part of our immune system don’t work as well in an acidic environment.

7

A blood-sugar level of 120 reduces the phagocytic index—a measure of how well immune-system cells gobble up bacteria—by 75%.

8

Since refined sugar comes with no nutrients of its own, it uses up certain mineral reserves of the body that are needed to metabolize it, which in turn throws off mineral balances and results in nutrient depletions.

9

(One of the minerals that refined sugar depletes is chromium, which is needed for insulin to do its job effectively!) Since minerals are needed for dozens of metabolic operations, these mineral deficiencies can wind up slowing down your metabolism and creating havoc with your energy level. Finally, sugar reduces HDL, the helpful, “good” cholesterol, adding yet another risk factor for heart disease to its résumé.

10

Is it any wonder that people drastically improve their health when they switch to a diet lower in sugar?

Why Should We Care about High Levels of Insulin?

Now you understand the problems caused by high levels of sugar in the blood. But what problems are associated with high levels of

insulin

? See, insulin doesn’t just bring your blood sugar down, call it a day, and go home. It affects many other systems as well. Bringing in a huge amount of insulin to fix the sugar problem is like importing twenty thousand workers to fix a broken power plant in your city. The city can’t run efficiently without electricity—hospitals are in danger, computers shut down, there’s no public transportation, and you can’t cook. So the prime order of business is to fix the emergency. At first, city officials aren’t thinking about the effect of that influx of workers on the rest of the city’s business; they just want to get the immediate problem fixed. Yet all those workers are going to have a major impact: the roads will be overcrowded, pollution will increase, crime may go up, and there will be additional demands for housing and food. But the city is faced with a life-and-death situation, so it imports however many people are needed to fix the problem. The same thing happens when the body produces high levels of insulin to cope with high blood sugar: damn the torpedoes, full steam ahead—the body will worry about the consequences later.

Insulin and Heart Disease

One of insulin’s many effects on the body is to make the walls of the arteries thicker. It does this by encouraging growth and proliferation of the muscle cells that line those artery walls. Insulin also makes the walls stiffer, reducing the “flow space” inside and increasing blood pressure. Smaller arteries are also more prone to plaque.

As we’ve seen, insulin also increases LDL cholesterol (the so-called “bad” cholesterol) in the blood. But despite what you may have heard, we don’t really care about that until that LDL is deposited on the lining of the artery walls. In fact, we

still

don’t need to worry about it unless that LDL becomes damaged. When it becomes damaged,

then

we have something to worry about. Damaged LDL attracts cells called macrophages, little Pac-Man–like creatures that come out to feast on the LDL like sharks on a bleeding carcass. When LDL is not damaged, the macrophages leave it alone, but as soon as damage occurs, the macrophages zoom in and feed, gorging themselves until they’re full, at which point they’re called “foam cells.” These foam cells group together and make a fatty streak, the first step in the formation of plaque.

How does the LDL get damaged in the first place? By two processes—oxidation, the interaction with oxygen that produces the same kind of “rusting” damage you see when you leave a cut apple out in the air; and glycation, bumping into sticky sugar. We just discussed how glycolated proteins cause all sorts of damage in the body. This same process of glycation damages LDL, and damaged LDL attracts macrophages like red flags attract bulls.

So insulin increases the amount of LDL in the system, and excess sugar damages the LDL, leading ultimately to plaque. If this were not enough to increase your risk for heart disease, you’re also going to have lowered levels of magnesium, a mineral that is absolutely essential for the health of the heart. Why is your magnesium level lowered? Because insulin, in addition to storing sugar and fat in the cells, is also responsible for storing magnesium, so when your cells become resistant to insulin, you lose the ability to store some of that magnesium. Magnesium relaxes muscles, including those in the arterial walls. When you can’t store magnesium, you lose it and your blood vessels constrict, causing a further increase in blood pressure. The loss of magnesium can also lead to heart arrhythmia and other cardiac problems.

11

And because magnesium is required for virtually all energy production that takes place in the cells, you may also find yourself with lower energy to boot.

How Does a Low-Carb Diet Lower Your Risk of Heart Disease?

There are numerous ways in which a low-carb diet can significantly lower your risk for heart disease. Lowering your insulin levels is certainly one of the most important. Raising your HDL (“good” cholesterol) is another. A third—the importance of which it is difficult to overstate—is by lowering triglycerides. Researchers from the cardiovascular divisions of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, in a study led by J. Michael Gaziano, looked at various predictors for heart disease and found that the ratio of triglycerides to HDL was a better predictor for heart disease than anything else,

including

cholesterol levels. They divided the subjects into four groups according to their ratio of triglycerides to HDL and found that those with the highest ratio (i.e., high triglycerides to low HDL) had

a sixteen times greater risk of heart attack

than those with the lowest ratio (low triglycerides to high HDL).

12

There’s more. Most of us are familiar with “good” cholesterol (HDL) and “bad” cholesterol (LDL), but what is not as well known is that both types of cholesterol have sub-parts that behave very differently from one another. What

kind

of LDL you have turns out to be much more important than just the

amount

of LDL you have (an LDL-gradient-gel electrophoresis test is now widely available to tell you about your LDL). For example, LDL cholesterol comes in two basic flavors: it can be a big, fluffy, cotton ball–like molecule (LDL-A type), or it can be more like a dense, tight BB-gun pellet (LDL-B type). The big, fluffy LDL-As are pretty harmless. They are far less likely to become oxidized or damaged and cause problems. But the little LDL-Bs are a different story. Those are the ones that cause problems, and those are the ones you should be concerned about. The Gaziano study found that high triglycerides correlate strongly with high levels of the dangerous LDL-B particles, and low levels of triglycerides correlate with higher levels of the harmless LDL-As. In other words, the higher your triglycerides, the greater the chance that your LDL cholesterol is made up of the B-particles (the kind that is way more likely to lead to heart disease). The take-home point: reduce your triglycerides (and raise your HDL), and you reduce your risk of heart disease.

Insulin and Hypertension

As you saw in the previous paragraphs on heart disease, high levels of insulin can narrow the arterial walls which, in turn, will raise blood pressure, since a more forceful pumping action is required to get the blood through the narrower passageways. But there’s an even more insidious way in which insulin raises blood pressure.