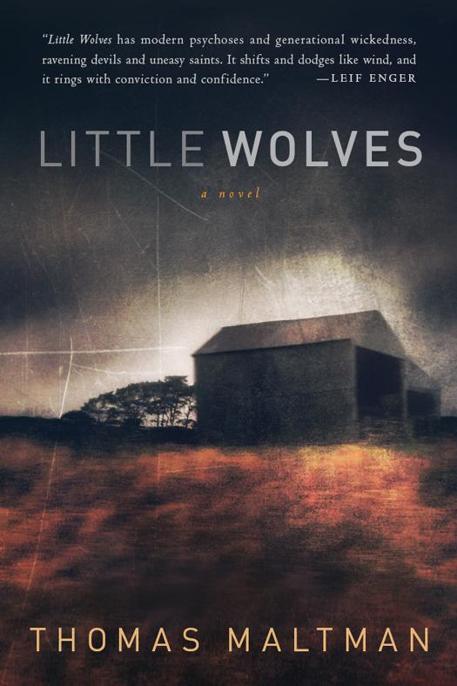

Little Wolves

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Copyright © 2012 by Thomas Maltman

All rights reserved.

Published by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Maltman, Thomas James, 1971–

Little wolves / Thomas Maltman.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-61695-191-7

1. Fathers and sons—Fiction. 2. Murder—Fiction. 3. Spouses of clergy—Fiction. 4. Family secrets—Fiction. 5. Minnesota—Fiction. 6. Psychological fiction. I. Title.

PS3613.A524L58 2012

813′.6—dc22 2012022678

Interior design by Janine Agro, Soho Press, Inc.

v3.1_r1

For my parents, Ruby and Doug, who instilled in me a love of places and of the stories those places hold

And ever and anon the wolf would steal

The Children and devour but now and then

Her own brood lost or dead, lent her fierce teat

To human sucklings …

—Alfred Lord Tennyson, “The Coming of Arthur”

Beauty is a terrible and awful thing! It is terrible because it has not been fathomed, and never can be fathomed, for God sets us nothing but riddles. Here the boundaries meet and all contradictions exist side by side.

—Fyodor Dostoevsky

,

The Brothers Karamazov

“We’ve been waiting for you, Judas,” Jesus said. “We couldn’t begin till you came.”

—Madeleine L’Engle, “Waiting for Judas”

Contents

The Wolfling

The Boy

Namesake

Gast

These Things to Be Done

Lone Mountain

Welcome to the Country

Wergild

The Cornfield

Swaddling

Wolfgirl

Shards

Boy from the Stars

The Grove

Little Wolves

Duchess

Trap

Rites

Boys and Guns

Loup Garou

The Wilding

Harvest

A Good Day’s Work

Lock-In

Into the Pit

Hewhosleeps

Advent

Haying Season

BOOK

ONE

THE WOLFLING

S

he heard him from the mountain, a voice high and thin, breaking the night’s quiet. The cry was such as her own children made when she was gone too long searching for food to bring back to the den. It was the cry of something blind and helpless, a cry of hunger. She heard it and she could do no other thing but go toward it

.

How it came to be alone in the tallgrass is a story for another time. She heard it with her sharp pointed ears and smelled it with her sharp black nose. Her nose told her the truth. It was not a wolf pup but a human baby, alone on a bed of prairie grass under the starry dark. She smelled on the breeze the horses that had come and gone, running hard. They had run away pulling a wagon that scarred deep ruts in the grass

.

Her paws stepped in these ruts, found the gouges the horses had torn from the prairie. She paused, suspicious, and sniffed the ground and raised her nose and sniffed the wind. They had been here, but they were gone, except the baby. In the torn grass she smelled the fear on the horses and in the air she smelled something burning. She knew the ways of the wind and fire out on the prairie. The fire was a breathing thing, ever hungry. The fire would be here soon and find where the baby lay in his nest of grass

.

She could not resist his crying because she was a First Mother who had birthed many children, and there were no others like her in this valley that smelled of smoke and terror. Her children had grown fat and happy until the coming of the Trapper the past moon, the Trapper who had killed her Mate, scattering the others, and then found the den where she had hidden her pups away

.

The cries of the human baby traveled through the night and found her ears and went into her ears and into her blood. The cries opened up places inside her that had not yet gone dry, where milk recently flowed from her nipples to feed her pups and make them strong. It hurt to make milk again

.

The coyote was skinny and mangy, her ribs poking from her pelt, and she needed food for herself, a plump mouse or jackrabbit. Here was this thing wrapped in a white cloth under the night sky. It had fallen from the running horses but the soft grasses had broken the fall. The running horses had not stopped for it. The child might as well have come from the stars themselves. And now it was alone here as she was alone. She did not think what to do, even if the baby bore the same tainted smell as the Trapper. Her body had told her when the milk rinsed out of her. She went toward it, sniffing tentatively at the corner of the cloth, and then touched the baby’s soft skin with her wet black nose. The baby quit crying. It gurgled, shocked

.

The coyote licked it with her tongue and tasted the salty skin. If she had not been a First Mother, if another of her kind had found this pink bundle in the grass, the story might have been different. She stood over the child and crouched down so that it might reach her nipples and suckle. Yes, it hurt to make milk again. Her milk flowed out of her, emptying her of all she had to give, but her heart was full, as full as the night sky above

.

When the child was done feeding she opened her jaws, clenched the white cloth, and lifted the child from the grass. She carried him away from the smell of burning where the prairie grasses would soon blossom with flames. The child rocked to and fro in his hammock of cloth. She took him in this manner to the place she called home, the mountain from which she had first heard his cries, the mountain where she had been alone for a time, but not any longer

.

Her father had told her many stories, and this was just one, the one that reached furthest back into history, when settlers had gone to war with the Indians, and after the massacre, one child was saved by a feral mother. Her father told stories of a giant who lived inside a mountain, of wolves and lost children and the monsters they later became. The stories he told were the only answer he had for the absence of her mother. Though he never said so outright, they were about a childhood place he would never see again. She did not set them down on paper until after her father died and she herself was six months pregnant, a pastor’s wife, a stranger living in a small town.

Her hand shook as she wrote the words. She was in the room that was to be the nursery, and it was bare except for a small desk she planned to use as a changing table and the rocking chair where she sat with a spiral notebook spread open on her lap. Aqua-colored light soaked the room from blue curtains drawn across the window.

Yesterday, one of her students had rung the doorbell while she was down in the basement. She had looked up through a grimy basement window and beheld tennis shoes and the ragged edge of a coat. She saw the legs of this scarecrow figure and nothing more. He rang and rang that bell, and she just stood rooted there. A cold hand touched her shoulder, bidding her to stay. Even the baby she carried inside her was still and waiting. The bell kept ringing in her brain a long time after the figure in the coat went away.

And now the bells were ringing at church next door, as though this were any other Sunday, but she would not be joining her husband in the sanctuary. As pastor’s wife she did not want to face the congregation after what had happened. Her husband’s parishioners would greet her and smile. They desperately needed good news, and she was it.

How are you? The baby?

They would lay hands on her. The child was not hers alone; it belonged to them as well. They would touch her hair as though she had returned from the dead. They would speak once more of angels.

No. She needed to be alone here. She opened her notebook and began to write, balancing it on one knee. She could hear organ music and recognized the strains of

“This Is My Father’s World” as the service began. Quaking voices. Such a gift, this murmur in her blood. The rocking soothed her, as did the words she scratched on the page with a fountain pen, a Montblanc Meiserstruck her father had given her when she graduated from high school.

Late last night she had seen the coyotes, three of them emerging from the cornfield late after dark. They did not howl at first but entered the cemetery behind the church with a short series of yips and barks, one and then the other, their calls braiding into a chorus, until eventually one howled in a language that was part of the great outer darkness. The coyotes weren’t supposed to be here; they were searching for something. They had come from the lone mountain like a storybook curse and roused the town with their plaintive singing, vanishing by daylight.