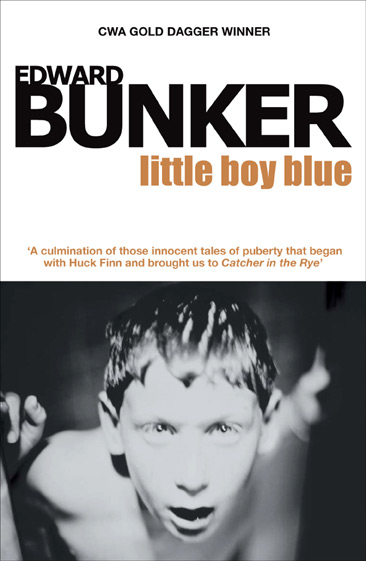

Little Boy Blue

Authors: Edward Bunker

Little Boy Blue

Edward Bunker

Contents

In the summer of 1943, a plain black Ford

sedan carried three people through the Cahuenga Pass from Los Angeles into the

San Fernando Valley. A middle-aged female social worker was driving. An

eleven-year-old boy was in the middle, and the boy’s father was on the

right. All of them stared through the windshield with somber faces. The social

worker looked stern, but it was really a practiced stoicism insulating her

emotions from the pain of sympathy. The father was silently determined, but his

determination was furrowed with worry; his jaw muscles pulsed as he sucked on a

cigarette. The boy’s lips were curled in until almost hidden, and

occasionally he bit them inside to stifle the smoldering tantrum. He was both

working himself up and restraining himself. Rebellion was coming, but this

particular moment was too soon.

Beyond Cahuenga Pass the large highway curved

to follow the base of the hills dotted with white houses buried in green

slopes. The social worker turned off onto a narrow, straight road through endless

orange groves. Every so often there was a flash of white as the car passed a

neat frame house set back from the road. The day was hot and the air

dusty,

and many insects splattered against the windshield.

Once they passed two bare-legged girls riding bareback on a fat mare. In 1943,

the San Fernando Valley was still the countryside—without smog and

without tract homes—where a few small communities were separated by miles

of citrus and alfalfa.

The boy stared ahead, as if transfixed by the

white line in the black road that disappeared in shimmering heat waves.

Actually he saw nothing and heard nothing. He was thinking of how many

identical trips he’d taken since he was four years old, to yet another

place to be ruled by strangers. It was nearly all he could remember—

boarding schools, military schools, foster homes—those places and

snatches of ugly scenes, tumult, and tears, the police coming to keep the

peace. Whenever he thought of his mother it was with her face contorted in

tears. He knew he disliked her without knowing why. He remembered the day when

his father walked out, and he had run after him, dragging a toy Indian

headdress, tugging at the car door and begging to go along. His father had

driven away, leaving him sprawled in tears in the dirt, and his mother had come

with a wooden coat hanger to make him scream even louder.

He remembered being in a courtroom but

nothing about what happened. Then his mother was gone, never seen again, never

mentioned.

After that began the foster homes and military

schools.

He couldn’t even remember the first one, except that

he’d been caught trying to run away on a rainy Sunday morning. His memory

images grew clearer concerning later places; he remembered other runaways, one

lasting six days, and fights and temper tantrums. He’d been to so many

different places because each one threw him out.

At first his rebellion had been blind, a

reflex response to pain— the pain of loneliness and no love, though he

had no names for these things, not even now. Something in him went out of

kilter when he confronted authority, and he was prone to violent tantrums on

slight provocation. Favored boys, especially in military school, looked down on

him and provoked the rages, which brought punishment that caused him to

run away. One by one the boy’s homes and military schools told his father

that the boy would have to go. Some people thought he was epileptic or

psychotic, but an electroencephalogram proved negative, and a psychiatrist

doing volunteer work for the Community Chest found him normal. Whenever he

was thrown out of a place, he got to stay in his father’s furnished room

for a few days or a week, sleeping on a foldup cot. He was happy during these

interludes. Rebellion and chaos served a purpose—they got him away from

torment. The time between arrival and explosion got shorter and shorter.

Now, as the tires consumed the dusty road,

the boy worked himself up, anticipating what he would do. Tears and pleas had

been futile, his father not deaf to them but helpless to change things. He too

had no choice. He was in his fifties, worn and thin, his skin red and leathered

from alcohol and laboring in the sun. He wasn’t an alcoholic, but in

recent years he drank a lot because of his wife, his son, and the Depression. A

good carpenter, he was proud of his craft, but work had been impossible for

nearly a decade. Only with the start of the war had he been working steadily.

He would have been happy except for his son. Why couldn’t the boy accept

the situation, the necessity of boarding him out? The man had told the boy

that the law required someone to look after him. If only there were a

family—aunts, uncles, cousins, friends—but both the man and his

former wife were orphans who had come here from southern Ohio, thinking that they’d

build a new life in sunny southern California. The man had an older sister who

lived in Louisville, but he hadn’t seen her for twenty years.

The man felt guilty about his son and salved

his conscience by paying more than he could afford on the military schools and

boarding homes. He scrimped on his own meals, lived in a cheap room. The boy

didn’t seem to notice the sacrifices. The man wondered if the boy was

crazy.

The man flipped his spent cigarette through

the window and suddenly felt angry. He’d spoiled his son. That was the

trouble. Only a spoiled boy would run away, fight, steal,

throw

tantrums. The man had done his best. He knew he’d done his best.

The social worker kept her hands firmly on

the wheel, her no- nonsense shoes on the gas and clutch. Traffic lights were

gauged early to shift down the gears. She’d learned to drive when she was

forty, having grown up where automobiles were not part of the landscape, and

she was always conscious of what she was doing. But with an empty road and

moderate speed, she had room to think. She could feel the boy beside her, his

body well known to the welfare agencies. Eleven years old and he’d

already accumulated a file.

A bright boy, in the top two

percent in intelligence, though his chaotic behavior and emotional problems kept

him from being a good student.

The boy had potential, but it would be

wasted. Years ago the situation would have

agonized

her, but for her own peace of mind she’d developed a protective shell

around her feelings. She did all she could to help but didn’t invest her

soul in a case. Too many cases failed, as if divorces and foster homes were

precursors to Juvenile Hall, reform school, and prison. This boy’s

chances for a successful life were very slim, made worse by his tempestuous

nature. His unique potential would develop into unique destructiveness. What a

pity, she thought, that there’s no direct relationship between the

intellect and the spirit. This boy needed a home and love for salvation, and

nobody could provide them, certainly no agency or institution.

“We’re early,” she said.

“We could stop for a bite somewhere.”

For a moment the man didn’t respond,

and then, as the words filtered through his reverie, he seemed startled. He

looked down at his son—a boy with a head too big for his body and eyes too

big for his head.

“You hungry, Alex?”

Alex shook his head, not wanting to speak and

break his gathering emotions. He needed everything for the looming

conflict.

The man, Clem Hammond, flushed. He too had a

temper. He shrugged an apology to the woman for his son’s churlishness,

thinking what his own father would have done faced with such a snotty attitude:

the stern farmer would have cut a switch and raised welts. Times had surely

changed, and not necessarily for the better. Yet Clem could understand Alex’s

misery, and he was sorry for being angry with the boy. “We could stop and

get some airplane magazines.” Then to the social worker he added

with pride, “Alex doesn’t like comic books.”

“I don’t want ‘em,”

Alex said, without looking around. His hands were pressed between his legs,

clenched into white-knuckled fists. Acid burned in his stomach, and tears

pressed behind his eyes. I don’t want to go there, he moaned inside

… don’t… don’t…

just take me

home, Pop. I’ll sleep on the floor and I won’t be any trouble…

please, Pop… please, God…

The silent prayer didn’t slow the Ford.

The orange groves fell behind, and now alfalfa fields glowed in the sun.

Whirling sprinklers threw off necklaces of sparkling water. The low

foothills that were the northern border of the San Fernando Valley grew larger.

The Valley Home for Boys was nestled at the base, shaded by eucalyptus,

pepper, and oak.

SCHOOL

ZONE DRIVE SLOWLY

Alex’s feet pressed the floorboard, his

body rigid, as if he could restrain their forward progress by willpower.

VALLEY

HOME FOR BOYS

A narrow road coated with fallen leaves was

behind the sign.

“I don’t like it,” Alex

said through tight jaws.

“How can you say that? You

haven’t seen it.” Clem was holding back his own anger. Hadn’t

he done all he could? He also saw the hints of a tantrum.

“It’s dirty,” Alex said.

The Ford went through sunlight mottled by the

overhead foliage. Stillness filled the grounds, a hush broken by occasional

trilling birds. But all living things were hiding from the August heat.

Everyone was tense. Alex’s eyes roved

like those of a small, trapped animal, and his breathing was thick, but he held

back the tantrum, waiting.

The road widened into a parking lot. Around

it

were

several two- story buildings with yellow tile

roofs; near the eaves the yellow was streaked. These were the dormitories. The

administration building was whitewashed frame that had seen better days. The

parking lot was nearly empty.