Little Black Book of Stories (13 page)

She said to Thorsteinn in one of their economical exchanges:

“There are living things here I can almost see, but not see.”

“Maybe, when you can see them,” he said equably, scribbling away with charcoal, “maybe then . . .”

“I am very tired, most of the time. And when I am not, I am full of—quite

abnormal

—energy.”

“That’s good?”

“It’s alarming.”

“We shall see.”

“DO HUMANS IN ICELAND, ”she asked again, conscious that

something

was staring and listening— uncomprehending, she believed—to the scratch of her voice—“do humans turn into trolls?”

“Trolls,” said Thorsteinn. “That’s a human word for them. We have a word,

tryllast,

which means to go mad, to go berserk. Like trolls. Always from a human perspective. Which is a bit of a precarious perspective, here, in this land.”

There was a long silence. Ines looked at his face as he worked, and could not focus the eyes that studied her so intently: they were charcoal blurs, full of dust-motes. Whereas the hillside was alive with eyes, that opened lazily within fringing mossy lashes, that stared through and past her from hollows in stones, that flashed in the light briefly and vanished again.

Thorsteinn said:

“There is a tale we tell of a group of poor men who went out to gather lichens for the winter. And one of them climbed higher than the others and the crag above him suddenly put out long stony arms, and wound them round him, and lifted him, and carried him up the hillside. The story says the stone was an old troll woman. His companions were very frightened and ran home. The next year, they went there again, and he came to meet them, over the moss carpet, and he was grey like the lichens. They asked him, was he happy, and he didn’t answer. They asked him what he believed in, was he a Christian, and he answered dubiously that he believed in God and Jesus. He would not come with them and we get the impression that they did not try very hard to persuade him. The next year he was greyer and stood stock-still staring. When they asked him about his beliefs, he moved his mouth in his face, but no words came. And the next year, he came again, and they asked again what he believed in, and he replied, laughing fiercely,

Trunt,

trunt, og tröllin í fjöllunum.

”

The English scholar who persisted in her said, “What does it mean?”

“

‘Trunt, trunt’

is just nonsense, it means rubbish and junk and aha and hubble bubble, that sort of thing, I don’t know an English expression that will do as a translation. Trunt trunt, and the trolls in the fells.”

“It has a good rhythm.”

“Indeed it does.”

“I am afraid, Thorsteinn.”

He put his bear-arm round the knobs and flinty edges that were where her shoulders had been. It felt to her lighter than cobweb.

“They call me,” she said in a whisper. “Do you hear them?”

“No. But I know they call.”

“They dance. At first it looked ugly, their rushing and stamping. But now—now I am also afraid that I can’t—join the circle. I have never danced. And there is such wild energy.” She tried to be precise. “I don’t exactly

see

them still. But I do see their dancing, the furious form of it.”

Thorsteinn said, “You will see them, when the time comes. I do believe you will.”

As the autumn drew in she grew restless. She had planted small gardens in the crevices of her body, trailing grasses, liverworts. Creatures ran over her—insects first, a stone-coloured butterfly, indistinguishable from her speckled breast, foraging ants, a millipede. There were even fine red worms, the colour of raw meat, which burrowed unhindered. She began to walk more, taking these things with her. In September, they had several days of driving rain, frost was thick on the turf roof, the glacial rivers swelled and boiled and ice came down them in clumps and blocks, and also formed where the spray lay on the vegetation. Thorsteinn said that in a very little time it would be unsafe to stay— they might be cut off. He watched her brows contract over the glittering eyes in their hollow caves.

“I can’t go back with you.”

“You can. You are welcome to come with me.”

“You know I must stay. You have always known. I am simply gathering up courage.”

WHEN THE DAY CAME, it brought one of those Icelandic winds that howl across the earth, carrying away all unsecured objects and creatures, including men if they have no pole to clutch, no shelter built into the rock. Birds can make no way in such weather, they are blown back and broken. Snow and ice and hurtling cloud are in and on the wind, mixed with moving earth and water, and odd wreaths of steam gathered from geysers. Thorsteinn went into his house and held on to the doorpost. Ines began to come with him, and then turned away, looking up the mountain-side, standing easily in the furious breakers of the moving air. She lifted a monumental arm and gestured towards the fells and then to her eyes. No one could be heard in this wailing racket, but he saw that she was signalling that now she saw them clearly. He nodded his head—he needed his arms to hang on to the doorpost. He looked up the mountain and saw, no doubt what she now saw clearly, figures, spinning and bowing in a rapid dance on huge, lithe, stony legs, beckoning with expansive gestures, flinging their great arms wide in invitation. The woman in his stone-garden took a breath—he saw her sides quiver—and essayed a few awkward dance-steps, a sweep of an arm, of both arms. He heard her laughter in the wind. She jigged a little, as though gathering momentum, and then began a dancing run, into the blizzard. He heard a stone voice, shouting and singing,

“Trunt, trunt, og

tröllin í fjöllunum.”

He went in, and closed his door against the weather, and began to pack.

Raw Material

HE ALWAYS TOLD THEM the same thing, to begin with “Try to avoid falseness and strain. Write what you really know about. Make it new. Don’t invent melodrama for the sake of it. Don’t try to run, let alone fly, before you can walk with ease.” Every year, he glared amiably at them. Every year they wrote melodrama. They clearly needed to write melodrama. He had given up telling them that Creative Writing was not a form of psychotherapy. In ways both sublime and ridiculous it clearly was, precisely, that.

The class had been going for fifteen years. It had moved from a schoolroom to a disused Victorian church, made over as an Arts and Leisure Centre. The village was called Sufferacre, which was thought to be a corruption of

sulfuris aquae.

It was a failed Derbyshire spa. It was his home town. In the 1960s he had written a successfully angry, iconoclastic and shocking novel called

Bad Boy.

He had left for London and fame, and returned quietly, ten years later. He lived in a caravan in somebody’s paddock. He travelled widely, on a motor bike, teaching Creative Writing in pubs, schoolrooms and arts centres. His name was Jack Smollett. He was a big, shuffling, smiling, red-faced man, with longish blond hair, who wore cable-knit sweaters in oily colours, and bright scarlet neckerchiefs. Women liked him, as they liked enthusiastic Labrador dogs. They felt, almost all—and his classes were predominantly female—more desire to cook apple pies and Cornish pasties for him, than to make violent love to him. They believed he didn’t eat sensibly. (They were right.) Now and then, someone in one of his classes would point out, as he exhorted them to stick to what they knew, that they themselves were what he “really knew.” Will you write about

us,

Jack? No, he always said, that would be a betrayal of confidence. You should always respect other people’s privacy. Creative writing teachers had something in common with doctors, even if—yet again—creative writing wasn’t therapy.

In fact, he had tried unsuccessfully to sell two different stories based on the confessions (or inventions) of his class. They offered themselves to him like raw oysters on pristine plates. They told him horror and bathos, day-dreams, vituperation and vengeance. They couldn’t write, their inventions were crude, and he couldn’t find a way to perform the necessary operations to spin the muddy straw into silk, or turn the raw bleeding chunks into a savoury dish. So he kept faith with them, not entirely voluntarily. He did care about writing. He cared about writing more than anything, sex, food, beer, fresh air, even warmth. He wrote and rewrote perpetually, in his caravan. He was rewriting his fifth novel.

Bad Boy,

his first, had been written in a rush just out of the sixth form, and snapped up by the first publisher he’d sent it to. It was what he had expected. (Well, it was one of two scenarios that played in his young brain, immediate recognition, painful, dedicated struggle. When success happened it appeared blindingly clear that it had always been the only possible outcome.) So he didn’t go to university, or learn a trade. He was, as he knew he was, a Writer. His second novel,

Smile and Smile,

had sold 600 copies, and was remaindered. His third and his fourth—frequently rewritten—lay in brown paper, stamped and restamped, in a tin chest in the caravan. He didn’t have an agent.

CLASSES RAN from September to March. In the summer he worked in literary festivals, or holiday camps on sunny islands. He was pleased to see the classes again in September. He still thought of himself as wild and unattached, but he was a creature of habit. He liked things to happen at precise, recurring times, in precise, recurring ways. More than half of most of his classes were old faithfuls who came back year after year. Each class had a nucleus of about ten. At the beginning of the year this was often doubled by enthusiastic newcomers. By Christmas many of these would have dropped away, seduced by other courses, or intimidated by the regulars, or overcome by domestic drama or personal lassitude. St. Antony’s Leisure Centre was gloomy because of its high roof, and draughty because of its ancient doors and windows. The class themselves had brought oil heaters, and a circle of standard lamps with imitation stained-glass covers. The old churchy chairs were pushed into a circle, under these pleasant lights.

HE LIKED THE LISTS of their names. He liked words, he was a writer. Sometimes he talked about how much Nabokov had got out of the list of names of Lolita’s class-mates, how much of America, how strong an image from how few words. Sometimes he tried to make an imaginary list that would please him as much as the real one. It never worked. He would write allusive equivalents—Vicar, say, for Parson, Gold, for Silver, and find his text inexorably resubstituting the precise concatenation that existed. His current class ran:

Abbs, Adam

Archer, Megan

Armytage, Blossom

Forster, Bobby

Fox, Cicely

Hogg, Martin

Parson, Anita

Pearson, Amanda

Pygge, Gilly

Secrett, Lola

Secrett, Tamsin

Silver, Annabel

Wheelwright, Rosy

He consulted this for pointless symmetries. Pygge and Hogg. Pearson and Parson. The prevalence of As and absence of Es and Rs. He had kept a register, for a time, of surnames reflecting ancient, vanished occupations—Archer, Forster, Parson, Wheelwright. Were there more in Derbyshire than in other places?

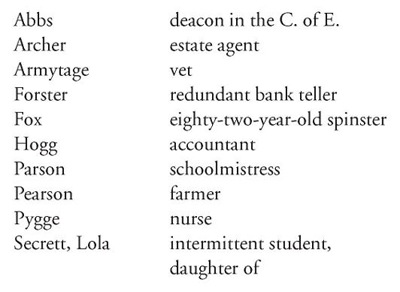

Then there was the list of the occupations, also a flawed microcosm.

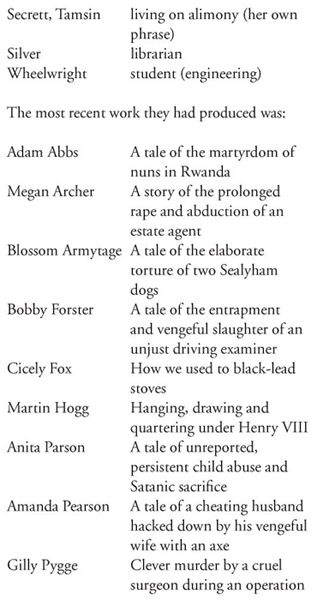

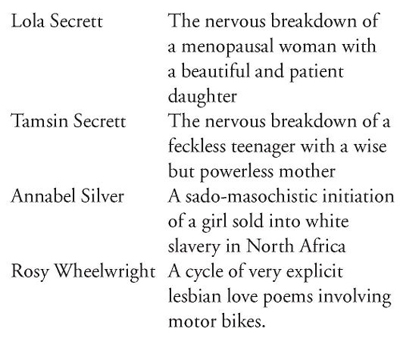

The most recent work they had produced was:

He had learned the hard way not to involve himself in any way in their lives. When he first moved into the caravan he had had a conventional enough vision of its warm confinement as a secret place to take women, for romping, for intimacy, for summer nights of nakedness and red wine. He had scanned his new classes, fairly obviously, for hopefuls, measuring breasts, admiring ankles, weighing pink round mouths against wide red ones against unpainted severe ones. He had had one or two really good athletic encounters, one or two tearful failures, one overkill which had left him with a staring, shivering watcher every night at the gate of his paddock, or occasionally peering wildly through the caravan window.

Creative writers are creative writers. Descriptions of his bedlinen, his stove, the blasts of wind on his caravan walls, began to appear, ever more elaborated, in the stories that were produced for general criticism. Competitive descriptions of his naked body began to be circulated. Heartless or cowering males (depending on the creative writer) had thickets, or wiry fuzzes, or fur soft as a dog fox, or scratchy-bristly reddish outcrops of hair on their chests. One or two descriptions of fierce thrusting and pubic clamping were followed by anticlimax, both in life and in art. He gave up— ever—taking women from his classes on to his unfolded settee. He gave up, ever, talking to his students one at a time or differentiating between them. The sex-in-a-caravan theme wilted and did not resuscitate. His stalker went to a pottery class, transferred her affections, and made stubby pottery pillars, glazed with flames and white spray. As the folklore of his sex life diminished he became mysterious and authoritative and found he enjoyed it. The barmaid of the Wig and Quill came round on Sundays. He couldn’t find the right words to describe her orgasms—prolonged events with staccato and shivering rhythms alternating oddly—and this teased and pleased him.

He sat alone in the bar of the Wig and Quill the evening before his class, reading the “stories” that were to be returned. Martin Hogg had discovered the torture which consists of winding out the living intestines on a spindle. He couldn’t write, which Jack thought was just as well—he used words like “gruesome” and “horrible” a lot, but was unable, perhaps inevitably, to raise in a reader’s mind any image of an intestine, a spindle, pain, or an executioner. Jack supposed that Martin was enjoying himself, but even that was not very well conveyed to his putative reader. Jack was more impressed by Bobby Forster’s fantasy of the slaughter of a driving examiner. This had some plot to it—involving handcuffs, severed brake cables, the removal of signs indicating quicksands, even an unbreakable alibi for the mild man who had turned on his tormentor. Forster occasionally produced a sharp, etched sentence that was memorable. Jack had found one of these in Patricia Highsmith, and another, by sheer chance, in Wilkie Collins. He had dealt with this plagiarism, rather neatly, he thought, by underlining the sentences and writing in the margin “I have always said that reading excellent writers, and absorbing them, is essential to good writing. But it should not go quite so far as plagiarism.” Forster was a white-faced, precise person, behind round glasses. (His hero was neat and pale, with glasses which made it hard to see what he was thinking.) He said mildly, on both occasions, that the plagiarism was unconscious, must have been a trick of memory. Unfortunately this led Jack to suspect automatically that any other excrescent elegance was also a plagiarism.

HE CAME to “How We Used to Black-lead Stoves.” Cicely Fox was a new student. Her contribution was hand-written—with pen and ink, not even felt-tip. She had given the work to him with a deprecating note.

“I don’t know if this is the sort of thing you meant when you said ‘Write what you really know about.’ I was sorry to find that there were so many

lacunae

in my memory. I do hope you will forgive them. The writing may not be of interest, but the exercise was pleasurable.”

How We Used to Black-lead Stoves

It is strange to think of activities that were once so much part of our lives that they seemed daily inevitable, like waking and sleeping. At my age, these things come back in their contingent quiddity, things we did with quick fingers and backs that bent without precaution. It is today’s difficult slitting of plastic wraps, or brilliantly blinking microwave LED displays, that seem like veils and shadows.

Take black-leading. The kitchen-ranges in the kitchens of our childhood and young lives were great, darkly gleaming chests of fierce heat. Their frontage was covered with heavy hasped doors, opening on various ovens, large and small, various flues, the furnace itself, where the fuel went in. Words are needed for extremes of blackness and brightness. Brightness included the gold-glitter of the rail along the front of the range, where the tea-towels hung, and the brass knobs on certain of the little doors which had to be burnished with Brasso—a sickly yellowish powdery liquid—every morning. It included also the roaring flame within and under the heavy cast-iron box. If you opened the door, when it was fully burning, you could hear and see it—a flickering transparent sheet of scarlet and yellow, shot with blue, shot with white, flashing purple, roaring and burping and piffing. You could immediately see it dying in the rusty edges of the embers. It was important to close the door quickly, to keep the fire “in.” “In” meant

contained,

and also meant, alight.