Lilla's Feast (42 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

The Communists were still in Chefoo. And not just in Chefoo, but in nearly all of Shantung except a narrow strip of land between Tsingtao and the inland city of Tsinan—one of just four strategic corridors in north China that the Nationalists were fighting to keep open. And which, within weeks of Lilla arriving in Tsingtao, the Communists would manage to close. Nonetheless, shortly before Lilla reached Tsingtao, her nephew Rugs had managed to make a brief trip back to Chefoo. He had sailed around the coast on a U.S. Navy transport ship with the U.S. vice-consul and six representatives of other countries. The only foreigners left in the town were the German civilians who had not been inprisoned but were now stranded there—their “home” country being in no state to pick them up. The American vessel stayed out at sea, and the group went into land on a launch, carrying signal lights to flash to the ship in case they found themselves in trouble. Once ashore, Rugs took them all to stay “at the house of a German friend from the old days.”

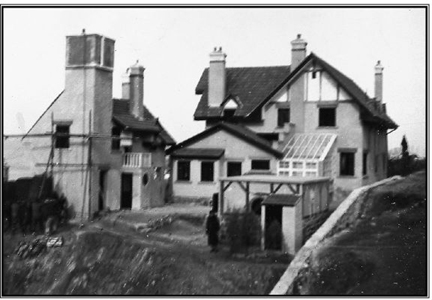

They stayed just under a week. Each of them visited as many of their nationals’ former houses and offices as they could. Rugs went to where Vivvy’s house, called Avalon, had once stood and took a couple of photographs of the few bricks scattered there. The Casey & Co. building still towered over the seafront but was very much occupied. And its new occupiers, whoever they were, had no intention of letting Rugs in. Once he had given up trying to gain access, he walked to the far end of First Beach and climbed East Hill to the remains of the Woodlands Estate. As in the rest of the town, the furniture and plumbing had been torn out of every house. But Lilla’s houses were still standing. Two of them still had glass in some of the windows. Rugs wandered through the buildings and made a few notes.

Avalon, Vivvy and Mabel’s home in Chefoo, before the Second World War

On his return to Tsingtao, he wrote up a lengthy report for the Consulate General in Shanghai. Lilla pored over its contents, and I think she took the description of every stone standing as hope that the town she remembered could come alive again. She couldn’t go back to Chefoo until Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists regained control. But surely they would. After all, a couple of months earlier, in March, a new Chinese National Assembly had been set up in Nanking. And Chiang Kai-shek had been elected president of it.

So Lilla decided to wait. Unaware that she, like the rest of her family in Tsingtao, was standing right in the enemy’s path.

While they waited, Lilla and Casey kept on trying to carry out some sort of linen trade from Tsingtao. But business was far from easy. Lilla’s niece Gerry and her husband, Murray, were finding it hard to restart his business of shipping frozen eggs to the United States. Vivvy and Mabel seemed to be having no luck at all and were “so pauperish” that they were living off chili con carne and little else. Still, they can’t have been completely penniless as—even though fruit and vegetables were abundant—any sort of meat at all was hard to come by. It was mainly available on the black market, and even with cash, it was hard to buy. “Rugs came back one lunchtime jubilant,” remembers Audrey, “to have found a ham.” The one form of protein that seemed to be in endless supply was caviar, sent in to the British consulate from passing Russian ships. At times, Reggie and his wife, Jessie, resorted to feeding it to their dog.

As the summer passed, Lilla’s hope that the Communists would be defeated began to look increasingly unlikely. Chiang Kai-shek’s first term as president of the new assembly was not proving a success. The country was still in chaos, and the assembly had decided to issue a new national currency. This was to be based on the price of gold and—perhaps ill-advisedly—required the surrender of all gold, silver, and foreign currency held by individuals. At this proposal, public opinion swung firmly against Chiang Kai-shek and his Nationalist Party. And at almost the same time, the military tide began to turn against them, too. In the bitter northern province of Manchuria—where the Nationalists had long been fighting off the Communists forces—the Communists were now gaining the upper hand. By the end of 1948, they had taken the town of Mukden and control of Manchuria with it. In January 1949, just as the Japanese had done a dozen years beforehand, the Red Army swooped down out of the windswept province.

It was two more months before the Red Army marched into Tsingtao. But long before the army’s arrival, the town was already feeling the effects of its advance. As the Japanese had removed the radiators from every house, the only form of heating was a coal stove in the kitchen. And the coal mines were now in Communist territory, so no coal was reaching the Nationalist-controlled areas such as Tsingtao. Once more, Lilla and Casey found themselves grubbing around in the dirt to make coal balls to keep warm. “Even the Chinese coolies found squatting in the mud to do this too degrading at any price.” At least there was still some electricity. Kettle by kettle, Lilla would have been able to heat herself a bath. Unless it rained—when the electricity shut down altogether. As the Red Army drew closer in the early months of 1949, even this capricious power supply grew more and more erratic. And a new hazard reared its head as “Nationalist bullets began to fly around the town indiscriminately.” Not even the supposedly inviolable British consulate was safe. One evening, bullets flew through its bathroom walls, narrowly missing Jean, who, then heavily pregnant, was maneuvering herself into the bath. Even the official consular car was fired at as it was trying to speed Gerry to the hospital before her new baby arrived. Already in the throes of labor, Gerry had to fling herself “to the floor of the car to dodge the bullets.”

When the Communist army eventually entered Tsingtao in March 1949, the Nationalist soldiers showed little resistance. They had been so poorly paid—if at all—that some took the opportunity of making a fast buck by selling their rifles to the advancing enemy before disappearing. Lilla’s hopes for a Nationalist victory in China must have disappeared with them. But as the red flags rolled into the town, I think she found herself nurturing the same optimism that had kept her going under the Japanese. Maybe, just maybe, once the Communists had settled down, sorted the country out, life in China could continue as before. Lilla wasn’t going to give everything up now. Not now that she was this close to home.

She’d spent so many years forcing herself to keep on going that she must have forgotten how to stop.

First to go were the books. All books—all evidence of learning, education, the old culture—were destroyed. It didn’t matter whether the books were on Chinese Confucian philosophy, which the Communists were particularly keen to eradicate, or were simply the American detective thrillers collected by Lilla’s nieces. It didn’t matter whether they were written in Mandarin, English, or German.

The Communist officials started with the libraries of the British-American Institute, the Tsingtao Club, the Masonic Hall. As if to demonstrate the extent to which Westerners and their culture were now the enemy, “every single book was carted away in wheelbarrows and burnt,” remembers Rugs. Then they moved on to the houses, where “all Chinese who worked for foreigners were ordered to inform on their employers or face unspeakable consequences.” The party officials turned each home upside down in their manic hunt for now-illegal literature. Even newspapers were destroyed. Audrey had packed some china in a combination of spare dressmaking material, underclothes, and old Chinese newspapers—every sheet of which was pulled out and destroyed, page by page. In one foreign family’s house, the Communists found something even more incriminating than books and papers: a photograph album containing pictures of half-Chinese, half-Western children. A suggestion that China could mix with the West. The political official who found that destroyed it on the spot.

Eventually, the Communists reached Lilla and Casey’s house in Iltis Huk. Lilla would have known they were coming. Would have been sitting on a kitchen chair, waiting for a knock on the door. When it came, she had to stand and watch them sweep through her home, picking up piles of business documents—just as those Japanese soldiers had done in the Casey offices in Chefoo. By now, Lilla must have begun to think that her optimism here in Tsingtao might be just as misplaced as it had been back then. At least this time, they hadn’t taken her husband away for questioning. Not yet.

Then the Communists seized control of all the businesses in the town. Or, rather, shut them all down, cutting off any chance of earning a living. It was as though Lilla had been caught up in some infernal historical loop where events were repeating themselves again and again, in slightly different shades of red. What would happen next, if she stayed, she must have wondered. Another camp?

This time, Lilla wouldn’t have been at all sure that she could do it, all over again, and still survive. Casey wouldn’t. He wasn’t a complainer, but his hands and legs were beginning to tremble. He was starting to mumble about seeing tigers hovering outside their house. And even if they did survive another camp, it was extremely unclear what would happen afterward. The Communists weren’t some foreign invading force like the Japanese. There would be no American army making its way across the Pacific to rescue them.

It must have been about now that Lilla realized she couldn’t stay the course of this war in China. As much as she longed to return to Chefoo, it wasn’t about to happen. She would have to go back to England—she couldn’t call it Home—and watch her grandchildren grow up while she plotted her return. Thankfully, the rest of the world wasn’t at war this time around, so she and Casey could still reach there.

But as soon as she tried to book a passage out of Tsingtao, Lilla discovered that it was already too late. She could no longer go anywhere at all. In order to leave, she was told, she needed an exit permit from the authorities. When she applied for permits, one each for her and Casey—an elderly Western couple who just wanted to be out of the way—she was refused.

There may have been no room for Westerners in Communist China. But Lilla’s new rulers were making it clear that they weren’t about to let her walk away yet. After what the Chinese felt the foreigners had done to their country—appropriating land for themselves, dominating its trade, and selling opium to millions of its inhabitants, turning them into addicts—they were going to make an example of their new prisoners first.

As the weeks passed, Lilla and Casey simply ran out of money. They had nothing left with which to buy anything at all. Not even food, which was becoming scarcer and scarcer. Together with Mabel and Vivvy, each day they trekked over to Reggie’s house, the British consulate, to eat and wash.

And then the interrogations started, just as Lilla must have feared. The Communists began hauling off all the young Western men for questioning, at eleven at night, at two in the morning. “I was questioned three times a days for two hours at a time,” says Rugs. Each time they were dragged out of their beds, Jack Polkinghorn and Rugs found themselves sitting in front of the same interrogators, in the same cell, being asked the same question, again and again and again. In Rugs’s case, it was “What day did you go to school?” As if the Communists were trying to obtain an admission that he was in possession of some of the education that they were so keen to destroy. Half asleep, confused, and scared—because he never knew whether one of his questioners might simply pick his gun up from the table and shoot him; they had already shot a German in this way while the Chinese British vice-consul had disappeared overnight—he struggled to remember what he had answered before. “You had to say just one thing, give the same answer again and again,” Rugs said. “It was very harrowing,” remembers Jack. “You never knew when they would turn up to take you away.” He was asked about “opium and religion,” both of which the Communists were against. “I had to reply, ‘I don’t know much about that,’ and look down as I spoke,” he told me.

Rugs and Jack were interrogated for three months.

This time, Lilla must have thought when she saw her battered and exhausted nephews, at least they have left Casey and Vivvy alone. Casey was now seventy-eight. Vivvy was seventy-two. Reggie was seventy. As British consul, Reggie seemed to have some immunity. But who knew how long it might last?

Lilla and Casey spent months trailing between Iltis Huk and the consulate in the center of town for meals and baths, the journey seeming longer every day. Months of Casey finding it harder and harder to make the trip, Lilla coaxing him there and back. And then, suddenly, in August 1949, the exit permits came through. Four permits. For Lilla, Casey, Mabel, Vivvy. The old folk. The old folk could go home, the new authorities said. Had to go home, they said.

But my home is here,

Lilla must have wanted to scream. But she couldn’t. She was lucky to be getting away alive.