Lilla's Feast (2 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

I went back to the Imperial War Museum for the first time since I was a child and read the recipe book under the reading-room dome. I went to the British Library to see if I could find out a little more about who did what when, and I unearthed that ballot box of letters—there because one of my great-great-uncles had become Foreign Secretary to the Government of India and a poet. And as I started to turn over long-forgotten stones, more letters and newspaper clippings emerged from the bottom of dusty attic boxes, from the backs of once-flower-scented drawers. And more photographs appeared. Some from the vaults of university libraries. Others from the albums once kept by Lilla’s identical twin sister, Ada, spirited over to me from New Zealand. And a few from the collections of each person I went to see.

Then there are the family stories. I tracked down a web of long-lost relations by plucking names from newspaper reports of weddings written a century ago and persuading inquiry directories to do national searches. I’ve discovered dozens of cousins I never realized I had. I flew from London to Vancouver and back, via a snowbound Minneapolis, to stay with one of Lilla’s nephews for the weekend and met a lady who remembered Lilla in the Japanese prison camp they had both been in. I found others scattered around the coast of England in Suffolk, Cornwall, and Kent. All of them have their stories to tell about Lilla. The things they overheard their parents discussing as children and the secrets she confided to them during her long years in England at the end of her life. There are non-family stories, too. Thousands of documents record the minutiae of Lilla’s home, the treaty ports of China—extraordinary enclaves of Western life that used to be dotted up and down its shores.

And the way in which each record has been kept tells me almost as much as its contents. Like the sepia portraits of British families and children, dressed as for a London street a century ago but taken, as the fraying cardboard around them reveals, in Shanghai. And it is not just how memories have been preserved, but why, that has been revealing, too. There are those British Library letters, self-consciously gathered by Lilla’s in-laws, the Howells, a family thoroughly sure of both its intellectual ability and literary skills (“they will very likely be interesting reading a hundred years hence if the world moves on as fast as it has done”). Several other key letters and files I have seem to have escaped the fire or wastepaper basket only because they make some reference to money and were therefore kept by people who had lost a lot of it and hoped that one day some might come back. And there are the letters and notes that have not survived—destroyed because the reader wanted to keep the correspondence tantalizingly private or because the writer assumed that nobody would be interested. As one of my many great-great-aunts in this story writes of her diary, “as I am not very likely to become famous and have a biographer, I have burnt it.” Oh, how I wish she had not.

Even the stories I have been told face-to-face vary in nature according to the teller and to what they have found interesting enough for their memories to retain: detailed accounts of great journeys, moments of battle, business deals, and mouthwatering meals from my male relations; the intricacies of who said what to whom when, loves, heart-breaks, homes, clothes, possessions, and eating habits from the women. Some old and lonely by the time I found them, their minds still fixed on a glorious past.

However, it is far from new to declare that all “facts” are inextricable from the person and medium used to record them. As Queen Victoria wrote, “I had long learnt that history was not an account of what actually happened, but what people thought had happened.” I haven’t attributed every single fact given to me to the particular source that provided it. To do so would make the text unreadable. In many cases, I have been given so many accounts of a single episode—each providing a different camera angle on Lilla’s life—that the only intelligible way of reproducing them has been to edit them into a single movie. Nevertheless, where it adds to the understanding of the story and is not self-evident, I explain how details came to light.

But by far the hardest question surrounds the gaps in the story. Where, sleuthing again, I have had to deduce how it must have felt to Lilla to be in a certain place, at a certain time. I read her recipe book again and again, my mind tasting the food she loved to cook. I went to China and marveled at the beauty of the bay in Chefoo where she was born. My sister and I ate cakes in the grand hotels of Shanghai, as Lilla and her sister once did. I put on her shoes and walked through her life with her. Where Lilla smiled, I smiled; where she cried, I cried; and where she made decisions that today seem strange, I began to understand what she had done. After all, I knew Lilla. The blood of her stories runs in my veins. Standing there with her, in other times, in other worlds, I closed my eyes and could almost see and hear what must have happened to her. Could imagine what she might have thought and felt.

Lilla’s story is not large-scale history. She was not a grand or famous person orchestrating world politics. She was in many ways very ordinary, a typical woman of her time—and this is a story of what large-scale history does to the small-scale people caught up in its events. There were a lot of events—two world wars, a couple of civil wars, and a complete change in the choices open to women in the Western world. When Lilla was born, she was brought up to be a wife and nothing else. But she ended up working and starting her own business. And I hope that my two children, who never had a chance to meet Lilla and to whom this book is dedicated, will take its most enduring lesson to heart. That is, however bad things may be, somewhere inside all of us is the strength of spirit to overcome them. Never give up hope.

London, January 2004

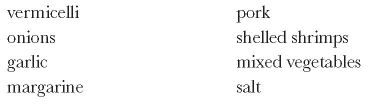

Shrimp Pork

To serve say five people: 3/4 lb vermicelli (boiled until soft), 3 large onions, ½ lb pork cut into dice when fried in the margarine until tender. Chop the onions and fry until golden brown, shell the shrimps about 4 ozs, prepare the vegetables then cut into small pieces. If garlic is liked, chop a very small piece. Boil the vegetables.

When all is ready, add onions, drained vermicelli, pinch of salt, chopped pork, vegetables (about 2½ lb), shelled shrimps. Put into a saucepan and heat until very hot.

Sometimes an omelet is made and placed on top, also dry rice is served in small bowls, with drops of soya sauce over.

Chapter 1

THE SWEET SMELL OF SPICE

CHEFOO, NORTH CHINA, THE SECOND-TO-LAST DAY OF MARCH 1882

Ada was born first, taking Lilla’s share of good luck with her. Or so everyone said. I’m not sure whether this was a Chinese myth to do with twins or just some family comparison of their two lives—for who can resist comparing the lives of twins? But when Lilla struggled into the world thirty minutes after her sister, she wailed, fists clenched, as if she already knew that she was going to have to fight to make up for being born without her fair share of fortune.

As far as the amah who looked after the two of them was concerned, Ada was Number One Daughter and Lilla, Number Two. When the amah picked up Ada to be fed first, Lilla learned to scream so that she was not forgotten. On the cold, dark mornings of those freezing north China winters that numbed the babies’ fingers and noses, Ada was the first to be swaddled in layers of warm clothes and Lilla had to shout to show that she was cold, too. The moment that a thick, slippery, silk ribbon was carefully woven into Ada’s plaits, Lilla pushed through her stutter to demand one for herself. And if Ada’s ribbon was pink, Lilla made sure that she had a pink one as well. “Right from the start,” I was told, “they had the most terrible fights—their shoes had to be put on each foot at the same time.”

To look at, Lilla and Ada were identical. Rummaging through the archives of the School of Oriental and African Studies at London University, I found a photograph of the pair of them, taken by a visitor to Chefoo when they were about eight years old. In it, they both have exactly the same pale, heart-shaped faces with high cheekbones and delicately pointed chins and noses. And the same long, dark brown—almost black—hair and bright blue eyes.

But only one of them is smiling. And I cannot tell which.

It was when the twins began to move around and talk—developing a twinly private language almost as soon as they did—that a difference emerged between them. The moment Lilla opened her mouth, her stutter betrayed her, while Ada spoke in smooth, clear tones. And when the pair of them started to totter around their redbrick, two-story, end-of-terrace home in the Chinese port of Chefoo (correctly pronounced “shee-fu” but anglicized to “chee-foo”)—a house designed to give its inhabitants the illusion of living in a safe British town—it was always Ada who went first. Lilla, a few paces behind, struggled to catch up with her elder sister as, black-booted and white-frilled, they clattered down the steep stone steps that led from the grand European villas and mock castles on Chefoo’s Consulate Hill to its port. There, they peered out over a harbor full of junks and, beyond them, to a volcanic reef of green pointed islands, like the spines on the back of a storybook dragon sitting down in the water. They watched as a coastal steamer from Shanghai slid through the water and a regatta of tall, swaying sailing ships and puffing, coal-driven barges from India, from Russia, from Japan, some even straight across the Pacific from San Francisco, nudged their way into moorings. They saw hundreds of barefooted coolies staggering up and down gangplanks—loading silks and peanuts to go to every corner of the world and unloading packages of narcotic brown powder from the hills of India—their conical straw hats shielding their dark-ringed eyes from the sun and hiding their sidelong glances in the direction of the sweet-smelling smoke seeping out from the doors of the opium dens.

And when Lilla and Ada played at being grown up, they strolled down the gentle slope on the far side of Consulate Hill that slid into the higgledy-piggledy beachfront. They promenaded, tiny parasols in hand, alongside the rattle of rickshaws and the pong of mule carts that wafted into the sea air. They wandered past the whitewashed Western holiday hotels, past the clink of glasses on the suburban-style Chefoo Club terrace, and past the square, squat tower of the austere St. Andrew’s Church with its triangular hat of a spire.