Lilla's Feast (18 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Lilla and Ernie’s cottage in Bandipur, Kashmir, 1904

Kashmir is an imposingly beautiful and heartlessly cruel country. Its Himalayan summits rise up through the landscape like Olympian gods looking to the sky. In between their ridges and peaks, the ground falls away precipitously, its cliffs eventually softening into rocky tundra that in turn flattens out into grassy slopes, tree-filled pastures, and roundbottomed glacial valleys. Down here, meadows amble beside a water garden of rivers, streams, and lakes. Dotted alongside, Kashmiri shacks, cottages, and houseboats sit as if in the lap of the gods. In the summer, these pastures fill with flowers, larger, brighter, and more abundant than seems possible in real life. But when winter comes, the temperature falls far below freezing, and snow buckets out of the sky, its blizzards wrapping themselves around each building, each tree, like a great winter coat, and in the lap of the gods is exactly where the Kashmiris are.

Lilla brushed aside Ernie’s concerns about the house, declaring it “quite snug and cosy” in her letters. When they arrived there in late November, it probably was. The vast mountain walls that surrounded the valley were already iced white, but the heavy snow wouldn’t spread across the low ground until January. However, when the winter proper came, it would be tough. In summer, Bandipur may have been a welcome retreat from Srinagar; but, apart from the local Kashmiri village, in winter, Lilla and Ernie risked being cut off from the outside world.

Lilla, though, viewed this impending onslaught of the elements as a challenge. Making a home against the odds like this was exactly what she knew how to do, longed to do. And in so doing, she must have thought, she could win Ernie round irrevocably.

She had a month before the snow arrived.

The house at Bandipur had just four rooms, and Lilla, Ernie, Arthur, and Mrs. Desmond were likely to be confined to this space for the best part of the winter months. The snow would be too deep, the temperature too low, to wander outside much. In any case, there wasn’t anyone to go and visit. Lilla’s first priority was to create a civilized living area for Ernie and herself. “I have made the front room my drawing-room,” she wrote to her sister-in-law Ada Henniker, so thrilled to have a home of her own at last that she gave her every detail of the house. “At last I am able to write and tell you how comfy we are in our little hut.” Next door was a room leading onto an L-shaped veranda, which she made their bedroom. On the far side of the house she put Arthur and Mrs. Desmond in a bedroom and nursery—“the latter is so nice, that I am sure many a nurse and child at home would envy.” It was hardly a separate wing, but it would at least give her and Ernie some space of their own. In order to keep out some of the cold, she had the veranda outside Arthur’s bedroom boarded up; “it makes a splendid hall.”

Ernie’s camp furniture had been replaced by some bought by his sister Ada and her husband, Fred, when they had stayed on a houseboat in Srinagar over the summer. True to Howell form, it wasn’t the most comfortable of furniture, but Lilla had to do what she could with it. She dug through the trunks and boxes of their possessions that had been sent up from Calcutta. Two years after their wedding, she was now unwrapping some of their 250 wedding presents for the first time. Unraveling great bandages of yellowing tissue paper from delicately painted china plates. Heaving great silver bowls and candlesticks from dust-covered crates and arranging them around her “drawing-room,” their grandeur charmingly out of scale with the cottage rooms. Finding great swaths of silks and cottons brought from China that she draped over the awkward furniture. And from the bottom of one of the boxes, she unearthed a heavy embroidered silk cloth that Ernie recognized as his trophy from when he had ransacked the Forbidden City with Toby after the Boxer Uprising. Lilla sewed quilting onto the back and turned it into a thick bedspread for their bed. At night, they snuggled together under this constant reminder of his military prowess. “She has made this hut so comfy,” wrote Ernie, glowing with husbandly pride.

Shortly after Christmas, the snow began to fall. Its heavy flakes curled around the house, turning their view across the valley into a fuzz of gray. Over the first few days, the morning sun melted it into slush and mud that froze back into an ice rink at night. And then, as the earth hardened, the frost spreading down through its layers, Bandipur turned white. The nearby lake froze over, first slowing into an eerie, viscous calm, and then great patches of white began to spread across it, the last glimpses of dark water eventually sealed away beneath the smooth sheet of ice. The snow deepened. Foot after foot was dug away from the sides of the house, and, finally, the falls seemed to ebb. The weather had done its work. The valley was still. Most of its creatures had burrowed themselves away against the cold; even the black Himalayan bears had vanished until spring. The cries of the few birds still darting from one white-limbed tree to another were muffled by the snow. Even the raging torrent at the bottom of their garden had slowed into a stiff icy flow. Winter had come.

Inside their cottage, Ernie and Lilla settled into snowbound domestic bliss. Ernie was besotted with his busy little son, accrediting all his achievements to Lilla: “He has inherited his mother’s cheery disposition.” Arthur charged around the house in the long, frilly white skirts and dresses that babies and toddlers of both sexes wore then. “So plucky,” boasted Ernie in his letters to his family, “bangs of all sorts he administers to himself but not one whimper.” From time to time, Arthur slept in his parents’ room. “He sleeps always on his face as I do,” wrote Ernie. “He awakes I don’t know how early but Lily has taught him not to make a sound until the bearer knocks at the door at 7 am,” when “the little chap jumps in his bed & says ‘atcha’ or ‘over’ or ‘oh dear.’ ” Upon hearing his son, Ernie would leap up and rush over to the cot to “take the little monkey into our bed.” And, in an astonishing gesture that would still score points for new manliness today, he changed him. “I usually pull off a mass of sodden garments—how he can stick them I don’t know.” If anything irked Lilla, she didn’t show it. She is “always good-tempered,” Ernie wrote to his mother.

Day and night, Lilla kept fires roaring in each room and the kitchen churning out steaming dish after steaming dish of poultry and game, plundered from the “farmyard” of turkeys, geese, ducks, pigeons, fowls, and cows kept around the house and occasionally bagged by Ernie himself on snowy forays with a shotgun. The only other source of provisions—the villagers had little to spare—were deliveries, weather permitting, from Srinagar. At first, Lilla would have kept Ernie’s food simple, familiar, stuck to dishes that she knew he would like. Roasting pheasants coated in fatty rashers of bacon. Stuffing long-necked wild ducks with sage and onions. Simmering sausage-stuffed wood pigeons in thick tomato soup and claret. Stewing and baking tiny rabbit joints with sultanas. Jugging hare, steaming it in a sealed earthenware dish for hours on end.

Once she sensed that she had lulled Ernie into a steady rhythm of expectation and gluttony she must have begun to branch out, spicing the dishes up into the curries he had professed to miss in London. Bit by bit she would have added new ingredients. Her recipe book is full of surprising dishes that put bananas into savory sauces and mix stir-fried peanuts with chicken to make a pilau. Then the pilaus slide from Indian to Chinese, with Lilla shredding the chicken, pulping the rice, and coating the dish in the Worcestershire sauce that she used instead of soy. Ernie must have wolfed it all down, showering praise over chopped duck and sliced chestnuts and strips of chicken strewn with dark mushrooms. Making Lilla feel that, at last, she had him entranced.

After dinner, Lilla played the piano to Ernie and sang, even persuading him to join in. Ernie agreed to let her teach him the violin. He was not a natural musician, but he tried his best. “He is now learning the violin obligato to my song ‘O dry those tears,’ it really sounds quite grand,” wrote Lilla. The two of them practiced together every evening, and Lilla—perhaps with a touch of womanly deception—clearly made Ernie feel that he was rather good. “I am much interested in it,” he wrote.

Engulfed in a haze of roaring log fires, music, paternal pride, and mouthwatering food—“she feeds me so well”—Ernie fell completely under Lilla’s spell: “It was really the best day’s work I ever did when I proposed to her. No man has ever had a nicer wife.” While he was stuck up on the Kashmiri mountainside, his old prejudices melted away: “There is no mistake she is not rich but money will not buy her charms, her natural grace, perfect figure, perfect teeth & complexion.” And Ernie even seemed to realize, in his own way, that their future happiness was in some measure up to him: “I must do all I can to make things easy for her. She must find Bandipur a great change from Bedford.” Lilla herself felt in charge. “He [Ernie] was certainly run down before, but now he is a different boy, and enjoys life, and does not worry one bit—I hope there will be no necessity for me to leave him again, as it does him no good to be alone.”

And for a precious few months, Ernie even stopped referring to Lilla in the double diminutive of “little Lily.” “Lily,” once Lilla had acceded to it, was there for good. Perhaps she sensed that Ernie was happiest thinking of her as smaller than him, given that he wasn’t a very tall man himself. And, unlike his father, who took an extremely active interest in his daughters’ education, Ernie’s view of women, with the exception of his sisters, was that of most men of his generation—they were lesser creatures.

Despite the new lease on life in his marriage, Ernie was still deeply frustrated at being snowed in. “I hate this weather,” he wrote. And despite Lilla’s best efforts to keep him entertained, he prowled around the house like a wounded tiger, bemoaning the difficulty of walking through the “several feet of snow” that surrounded the house, until at last the sleigh they were having built in the village was finished. Then, leaving Mrs. Desmond to wheel Arthur up and down the boarded-up veranda—only his eyes were visible “as he was so wrapped up in rugs, etc.”—they set out “nearly every afternoon” to go shooting on the frozen lake. These trips, however, rapidly turned out to be more amusing than practical. “There are thousands of birds,” wrote Lilla, “but they know the gun too well and fly away before we can get near them.”

Ernie was not to be put off his prey so easily. Determined to catch some geese, he cobbled together what he called a

mitrailleuse

from ten Brown Bessies—“medieval weapons with which the Kashmiri troops are armed.” He tied the guns into a rack on a wheelbarrow and camouflaged himself in one of Lilla’s nightdresses “to match the snow.” He loaded the guns with a “double charge of powder and buckshot,” attached all ten triggers to a single string, and crept toward the birds. When he had managed to maneuver himself within eighty feet of them, he pulled the string. The resulting bang sent the wheelbarrow careering into his chest “and made me roar with pain.” But he had a goose.

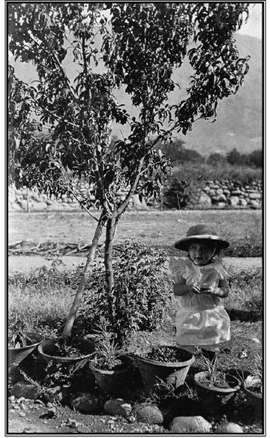

Arthur, Bandipur, Kashmir, 1904

Still wearing her nightdress, he returned to Lilla triumphantly, clutching the dead bird. It took three hours to roast. She turned the giblets into gravy, pounded some of the autumn’s apples into a sauce, and presented Ernie with a feast of his spoils.

By April, the snow was beginning to melt. While the rest of India began to heat itself to boiling point, a gentle spring settled on Bandipur. Lilla and Ernie’s family life moved outside. Arthur ran around with the animals and on the lawns. Lilla and Ernie showered him with presents. At barely one and a half years old, he had a pony, a puppy, and even a goat cart built for him, in which he sat—still in white frills, with a tent of a sun hat and parasols to shield him from the sun—clutching on to the reins.

As soon as it was warm enough to sleep away from a fire and before so much snow had melted that the rivers had returned to raging torrents, Ernie and Lilla escaped from their little hut and into “camp” on another Kashmiri houseboat. They ambled down the rising rivers, visiting waterfalls and springs, old temples and ruined palaces, sometimes abandoning the boat to camp in tents in the hills for several days at a time, listening to great spring avalanches roar down the mountains at night. When they returned with the rare birds that they had shot, Lilla had them stuffed and sent them back to Ernie’s sister Laura and her husband, Sidney.

Now Lilla could do no wrong. Every one of Ernie’s letters to his family was packed with praise for her. And by joining in Ernie’s family tradition of collecting rare species of plant and animal, and following the instructions she was given to add to Laura’s letter collection back in England—“when you have a good many of our effusions, send them home in a packet”—she was showing them that she could do far more than just run a house and cook. Lilla even managed to take the upper hand in her relationship with her mother-in-law, writing to Barbie, “give my fondest love to your mother and say, I do mean to write.”

But a single dark cloud loomed on the horizon. I had been wondering why Lilla had not pasted any snapshots of herself in Kashmir into her photo album. Then, in one of her letters to Barbie, the answer emerged. Perhaps I should have guessed it sooner. After all, it seemed to be an immediate, inevitable result of any union, or reunion, between Lilla and Ernie. I must have been distracted by all the banter about Ada. By Ernie’s amazingly indiscreet written whispers to his sisters not to “say one word about this [for] awhile”—but, “in spite of all precautions,” his wife’s twin was “in for an infant apparently to her great disgust.” So distracted was I by thinking that Ada’s “disgust” must have been masking a fear of having to watch another child die, I failed to notice all this while there had been not one murmur about Lilla. But she was pregnant, too, just a month behind her twin.