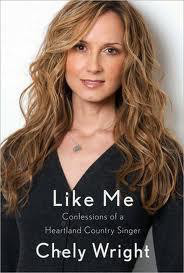

Like Me

Authors: Chely Wright

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Individual Composer & Musician, #Reference

For my family

History will have to record that the greatest tragedy of this period of social transition was not the strident clamor of the bad people, but the appalling silence of the good people.

—

MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR

.

My First Recording Contract, 1993

“But Didn’t She Date What’s-His-Name?”

Knee-Deep in a River and Dying of Thirst

“Hard to Be a Husband, Hard to Be a Wife”

Steel on Steel: Master Sergeant Wright

Keep Your Friends Close, and Your Enemies Closer

My Mom, My Brother, and Others

JANUARY 26, 2006

I

t has been twenty-eight days since she last spoke to me. How can she not call or reach out in some way? I have no idea if I’m going crazy or if I’m already there. Is this what it feels like?

I went to the doctor to get a checkup. Dr. Hock said I weigh 109 pounds. Last time I weighed myself, I was at 120. I have no appetite. I wake up crying, I go to sleep crying. I walk around my house in the middle of the night, from room to room, trying to find something to distract me, something to stimulate me, something to keep me from breaking down.

I’m afraid of the thoughts that I’m having. My only relief is when I’m sleeping. Sleep, however, is elusive. It mocks me, it teases me, it tortures me. When I am able to get rest, I risk dreaming of her. The dreams are happy ones, but then I wake and feel the truth bearing down on me, forcing the air out of my lungs, leaving just enough for me to cry. It’s like when I was a kid and got the wind knocked out of me and had to struggle to gasp the words “I can’t breathe.” I lie there hoping that I’m in a dream inside of a dream and that I will wake up.

I wonder if this is how it feels for everyone who is as broken as I am. I always assumed that people who committed suicide were somehow weak. Now I know how pain can seep into every cell of your body, and how hopelessness can shatter rationale and reason.

Later, when I try to explain my despair, I will be asked, “Did you really love her that much? Was losing her bad enough to make you want to die?” My answer will be no, but while I was going through it, I was certain it would destroy me.

On the twenty-eighth day after the breakup, my eyes slowly opened, beating the sunrise by fifteen minutes. I lay in bed, feeling every fiber of my muscles, the nerves behind my eyes, and every square inch of skin on my bony frame. Everything hurt. I’d been in my pajamas since New Year’s Day, except for a red-carpet event in downtown Nashville. “I’m going to come get you and carry you down the red carpet if I have to,” ordered my beloved friend and tour manager, Jan. “You’re going to get up, take a shower, do your hair and makeup, put on a dress, okay?” I didn’t have the strength to argue, and since Jan didn’t know about my secret or my broken heart, I gave in.

I noticed a vertical crease between my eyes that hadn’t been there before. At first, it appeared only when I cried, but I’d spent so much time crying that it had become permanent. Outside, it was so freezing cold that I kept to the third floor of my house, because it was a few degrees warmer up there. My grand piano was downstairs. If I could, I would have pulled it into bed with me. Instead, I picked up my Gibson J-200. I didn’t know how to play the guitar beyond a few chords, but songs were coming to me—pouring out of me, in fact. Most days I played until my fingers bled. I was convinced that the guitar and those songs were keeping me alive. When I’d finish a song, get it just right, do a simple recording of it in my home studio, another melody or phrase would scratch at the back of my throat or try to force itself out of the tips of my raw fingers. I needed a break, but I kept writing.

Two weeks into the breakdown, I stopped trying to fight off my anger. I couldn’t defend her to myself anymore. She’d cry to me, saying she didn’t know how she could fit us into her life. She promised she’d try, because she’d never loved anyone the way

that she loved me. She asked me to hang in there with her. Then she’d run away. I gave in to my frustrations with her and began to steep in my anger at the way society forces people like us into such dark places. And in the wee hours of an achingly cold day in the first month of 2006, I’d never been in a darker place.

I’d been in hiding most of my life and worked hard to protect my secret. No one like me in country music has ever admitted his or her homosexuality. There are gays in Nashville, but as far as anyone is led to believe, they are not those of us on the magazine covers. There is a slight understanding that there are gay publicists, songwriters, hair and makeup artists in the country music industry who help sell “straight” stars to the public, but that’s it. And even among them, few are truly out of the closet.

I was a successful recording artist, a video star. I’d made

People

magazine’s 50 Most Beautiful People list. Men in the armed forces asked me to autograph their Chely Wright posters. I’d been seen around town with a host of famous men—Brad Paisley, Vince Gill, Troy Aikman, and Brett Favre.

How could I be gay? Well, I am.

I reflect on a life that seems to be filled with all-American accomplishment. I was class president and homecoming queen in my senior year of high school. The Academy of Country Music’s Top New Female Vocalist. The first entertainer to play for our troops in Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein. I was the American Legion’s Woman of the Year and my home state’s Kansan of the Year. I founded Reading, Writing & Rhythm, a charity that has raised more than a million dollars for public schools. I am known to country music fans around the world as the singer of the #1 hit “Single White Female.”

On that morning, I realized my secret had caught up with me. I might be able to hide from Nashville and my fans, but I could no longer hide from myself. Even if I had been able to fight my way out of this emotional abyss, I’d still be lying. Lying had already cost me a twelve-year relationship with Julia, the person

with whom I once hoped to spend the rest of my life. Now it had claimed my relationship with Kristin, the woman with whom I’d just broken up. Denial and fear forced us apart. Denial and fear told Kristin it was better to hide than choose what her heart wanted. But I was no better. Behind closed doors I couldn’t be the real me. So on the twenty-sixth day of 2006, I decided it would be better to stop fighting.

I went upstairs to my bedroom, got on a stepladder, and reached up high into my closet. I easily located the loaded 9 mm handgun. It was heavier than I remembered. I stared at it for a few seconds, then made my way with the weapon down three flights of stairs to my first-floor foyer. The gun felt so strange in my hand. I didn’t hold it tightly; I carried it as if it were a dirty diaper or a piece of rotten food. I held it out and away. It made a clunking noise as I set it on the mantel of my entryway fireplace. I stood there, staring at it. I remember wondering how people do it. Do they put it to their temple and pull the trigger? Do they put it in their mouth? That made more sense to me; I didn’t want to miss. If I pointed it into my mouth, I probably wouldn’t miss.

I said a prayer to God to forgive me and to understand why I couldn’t go on anymore like this. I begged God to realize that I would never be able to fit into the life that I’d created. I hoped that God would realize that I would never be accepted.

I picked up the gun and put the end of it in my mouth. It was cold. I held it steady and got my right thumb on the trigger and prepared to pull it by pushing it outward. I looked up into the mirror, the one built into the mantel. I struggle now to fully explain what I saw staring back at me. My mouth stretched open with the end of a gun in it…My eyes were wide open, bigger than they’d ever been. It occurred to me that I wasn’t crying. Don’t people cry when they kill themselves? I recall thinking, “What if I do this and somehow my eyes stay open and whoever discovers me here sees my eyes like that?” So I closed my eyes …thumb still on the trigger. My mind went a million miles

a minute. I thought of my family, my dogs, my friends, my fans, the sun, a kiss from Julia, and music. Then I heard a noise.

It was the sound of my heart, pounding in my head. It grew louder and louder and I just knew that something was about to happen. I couldn’t stand here in my foyer with my eyes closed and a gun in my mouth forever. Then it happened—I started to cry. I opened my eyes and looked in that mirror as the tears poured out. I took the gun out of my mouth, put it back up on the mantel, and headed up to the third floor. I climbed in bed and stayed there for the next two days.

Dear God, please don’t let me be gay. I promise to be a good person. I promise not to lie. I promise not to steal. I promise to always believe in you. I promise to do all the things you ask me to do. Please take it away. In your name I pray. Amen.

I

said this prayer every single day of my life since the third grade. The words changed over the years, but the sentiment remained the same. The prayer was as much a part of me as my brown eyes, my long toes, and the chicken pox scar in the middle of my forehead.

I don’t remember a time when I didn’t believe in God. And I hardly remember a time when I didn’t know I was different. Slowly, I would learn that difference was something to be hated and feared. For most of my thirty-nine years, I’ve hidden my sexuality because I thought I had to. I was a small-town girl with a dream of moving to Nashville and becoming a famous country singer. The dream came true. But for all my success, I was left wrestling with a secret that could destroy everything I’d built. For decades, I swore I’d take that secret to my grave. Even as I write this, only a handful of people beyond my family and closest friends know that I am gay. But I’m done with hiding. I’m a proud Kansan, a loving daughter, sister, and friend, a child of God, and a lesbian. I was raised to know the difference between right and wrong. Telling my story is the right thing to do.