Life in a Medieval City (4 page)

Read Life in a Medieval City Online

Authors: Frances Gies,Joseph Gies

Tags: #General, #Juvenile literature, #Castles, #Troyes (France), #Europe, #History, #France, #Troyes, #Courts and Courtiers, #Civilization, #Medieval, #Cities and Towns, #Travel

Main routes to the Champagne Fairs

Some have already covered hundreds of miles by the time they reach the borders of Champagne. The cloth caravans from Flanders move south along the old Roman road from Bapaume. Merchants of the German Hanse follow the Seine in their oceangoing boats as far as Rouen, where they transship to shallow-draft vessels or hire animals. Italians sail from Pisa or Genoa to Marseille, or take the “Strada Francesca” from Florence to Milan. If they go by the latter route, they climb the Little St.-Bernard Pass in the Savoy Alps, led along precipices, through drifts, and around crevasses by guides in woolen caps, mittens, and spiked boots. Descending the western slopes, they follow the valley of the Isère to Vienne and Lyon. Here they are joined by merchants from Spain and Languedoc for the last leg of their trip, following the Saône valley north, or cutting northwest by way of Autun, or hiring boats and ascending the Saône.

In level country pack animals can make fifteen to twenty-five miles a day, carrying three to four hundred pounds. Couriers travel faster; the Flemish cloth merchants operate a service between the Champagne Fairs and Ghent which covers two hundred miles in four days. But it takes a company of merchants traveling from Florence to Champagne three weeks, even barring accidents. Because carts mire down in rainy weather, pack animals—horses, asses, and mules—make up the merchant trains.

Among the worst nuisances to merchants are the tolls. River crossings that range from the magnificent Pont d’Avignon to bad ferries and worse fords all charge tolls. So do many roads, even though built by the Romans.

Most of the fair traffic journeys in convoy, sometimes preceded by a standard-bearer, and with crossbowmen and pikemen guarding the flanks—a martial display which serves to advertise the value of the goods. Roads are actually safe enough, at least in the daytime. Besides, merchants en route to the fair enjoy extraordinary guarantees as the result of the treaties made by the counts of Champagne with neighboring princes. This very year, 1250, a merchant was robbed of a stock of cloth and squirrel skins while passing through the territory of the duke of Lorraine. Honoring his treaty obligation, the duke indemnified the merchant.

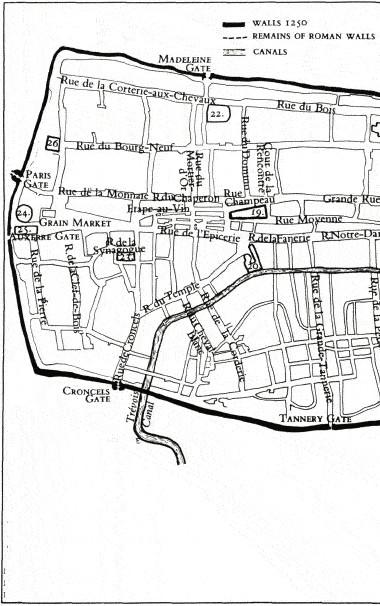

- 1.

CATHEDRAL OF ST.-PIERRE - 2.

BISHOP’S PALACE - 3.

COUNT’S PALACE - 4.

COLLEGIATE CHURCH OF ST.-ETIENNE - 5.

HÔTEL-DIEU-LE-COMTE - 6.

CASTLE OF THE COUNTS OF CHAMPAGNE - 7.

ABBEY OF ST.-LOUP - 8.

ST.-FROBERT (FORMER SYNAGOGUE) - 9.

PRIORY OF ST.-JEAN-EN-CHÂTEL (ST.-BLAISE) - 10.

PRIORY OF ST.-QUENTIN - 11.

CHURCH OF ST.-DENIS - 12.

CHURCH OF ST.-NIZIER - 13.

ABBEY OF ST.-MARTIN-ÈS-AIRES - 14.

CHURCH OF ST.-AVENTIN - 15.

PRIORY OF NOTRE-DAME-EN-L’ISLE - 16.

ABBEY OF NOTRE-DAME-AUX-NONN - 17.

CHURCH OF ST.-JACQUES-AUX-NONN - 18.

CHURCH OF ST.-RÉMI - 19.

CHURCH OF ST.-JEAN-AU-MARCHÉ - 20.

TEMPLAR COMMANDERY - 21.

DOMINICAN FRIARY - 22.

CHURCH OF STE.-MADELEINE - 23.

ST.-PANTALÉON (FORMER SYNAGOGUE) - 24.

VISCOUNT’S TOWER - 25.

CHURCH OF ST.-NICOLAS - 26.

HÔTEL-DIEU-ST.-ABRAHAM

The countryside through which the merchants approach Troyes is heavily wooded, but the past two centuries have witnessed considerable clearing and cultivating. Castles, villages, and monasteries have multiplied, surrounded by tilled fields and pastures where sheep and cattle graze. Immediately outside the city walls lie fields and gardens belonging to the inhabitants of Troyes itself.

An incoming visitor to the fair enters the city by one of the gates of the commercial quarter—from the west, the Porte de Paris or the Porte d’Auxerre; from the north, the Porte de la Madeleine or the Porte de Preize; from the south, the Porte de Cronciaus. The sand-colored city wall

1

is twenty feet high and eight feet thick, faced with rough-cut limestone blocks of varying sizes, around a core of rock rubble. Above it rise the roofs, chimneys, and church spires of the city. One crosses the dry moat by a drawbridge, passing through a double-leaf iron door flanked by a pair of watchtowers, powerful little forts connected by three passageways, one under the road, one directly above it and one on the level of the wall. Spiraling flights of stone steps lead from the towers to the vaulted interiors.

A party entering the Porte de Paris finds itself in the newest part of the city, the business quarter west of the Rû Cordé, a canal created by a diversion of the Seine. A hundred yards to the right rises the Viscount’s Tower,

2

originally the stronghold of the count’s chief deputy. The Viscount’s post has gradually evolved into a hereditary sinecure, at present shared by three families. The tower is a mere anachronism. Nearby, in a triangular open space, is the grain market, with a hospital named after St.-Bernard on its northern side.

Cats’ Alley

(Ruelle des Chats), Troyes’ most picturesque street, looks today much as it did in the thirteenth century, barely seven feet wide, with housetops leaning against each other.

Two main thoroughfares run east and west in the commercial section—the Rue de l’Epicerie, which changes its name several times before it reaches the canal, and to the north the Grande Rue, leading from the Porte de Paris to the bridge that crosses into the old city. It is thirty feet wide and paved with stone.

3

The Grande Rue is appreciably broader and straighter than the side streets, where riders and even pedestrians sometimes must squeeze past each other. The Ruelle des Chats—“Cats’ Alley”—is seven feet wide. Even on the Grande Rue one has a sense of buildings crowding in, the three-and four-story frame houses and shops shouldering into the street, their corbelled upper stories looming irregularly above. Façades are painted red and blue, or faced with tile, often ornamented with paneling, moldings, and sawtooth. Colorful signboards hang over the doors of taverns, and tradesmen’s symbols identify the shops. The shops open to the street, the lowered fronts of their stalls serving as display counters for merchandise—boots, belts, purses, knives, spoons, pots and pans, paternosters (rosaries). Inside, shopkeepers and apprentices are visible at work.

Most traffic is on foot—artisans in bright-colored tunics and hose, housewives in gowns and mantles, their hair covered by white wimples, merchants in fur-trimmed coats, here and there the black or brown habit of a priest or monk. Honking geese flutter from under the hooves of horses. Dogs and cats lurk in the doorways or forage for food with the pigeons.

The streets have been freshly cleaned for the fair, but the smells of the city are still present. Odors of animal dung and garbage mingle with pleasanter aromas from cookshops and houses. The most pungent districts are those of the fish merchants, the linen makers, the butchers and, worst of all, the tanners. In the previous century the expanding business of the tanners and butchers resulted in a typical urban problem. The bed of the Vienne became choked with refuse. Count Henry the Generous had a canal dug from the upper Seine, increasing the flow into the Vienne and flushing out the pollution. But the butchers’ and tanners’ district remains the most undesirable neighborhood in town. Cities such as Troyes legislate to make householders and shopkeepers clean the streets in front of their houses, and to forbid emptying waste water into the streets. But such ordinances are only half effective. Rain compounds the problem by turning the unpaved streets to mud.

The heart of the fair district surrounds the church of St.-Jean-au-Marché, a warren of little streets where the moneychangers have their headquarters, and where the public scales and the guards’ quarters are located. This area, half asleep all spring, is now humming. Horses clomp, hammers bang, and bales thud. Commands and curses resound in several languages, as sacks and bales from the ends of the earth are unloaded—savory spices, shimmering silks, pearls from the bottom of the sea, and wagonload after wagonload of rich wool cloth.

Fair merchants can lodge where they wish, but fellow-countrymen tend to flock together—businessmen from Montpellier on the Rue de Montpellier, near the Porte de Paris; those from Valencia, Barcelona, and Larida in the Rue Clef-du-Bois; Venetians in the Rue du Petit Credo, where the count’s provost has his lodge; Lombards in the Rue de la Trinité.

Tents and stalls are used only for the sale of secondary merchandise. The main transactions, in wool, cloth and spices, take place in large permanent halls scattered throughout the fair quarter, whose limits are carefully marked to insure collection of tolls from merchants. Several of the great cloth manufacturing cities have their halls in the Rue de l’Epicerie—Arras, Lucca, Ypres, Douai, Montauban. The hall of Rouen is in the Rue du Chaperon, that of Provins between the Rue de la Tannerie and the Commandery of the Knights Templar.

Near the canal, the Rue de l’Epicerie passes the ancient and powerful convent of Notre-Dame-aux-Nonnains and becomes the Rue Notre-Dame. Here, in stalls maintained by the convent, the Great Fire of 1188 began. To the south is the twenty-year-old Dominican friary (the Franciscans are outside the town, near the Porte de Preize). A little to the north, at the end of the Grand Rue, the Pont des Bains crosses the canal into the ancient Gallo-Roman citadel. On the right bank, above the bridge, are the public baths, where the traveler can scrub off the dust of the roads.

Across the canal lies the old city, still enclosed within its dilapidated Roman walls. Wealthy families live there, along with numerous clergy, officials serving the count, Jews in the old ghetto, some of the working class, and the poor. In the southwest corner of the square enclosure, its back to the canal, stands a large stone building, the count’s palace. The great hall rises over an undercroft, with the living quarters in the rear. In front of the palace stands the pillory, a wooden structure resembling a short ladder, which often pinions a petty thief or crooked tradesman. The count’s own church of St.-Etienne forms an “L” with the palace, so that he can hear masses from a platform at the end of his hall. Immediately to the north is the hospital founded by Count Henry the Generous, and at the northwest extremity of the old city rises the castle, a grim rectangular tower surrounded by a courtyard with a forbidding wall. The ancient donjon of the counts, the tower is today used as a ceremonial hall for knightings, feasts, and tourneys.