Life (9 page)

I had another job around that time, early teens. I did the bakery, the bread round at weekends, which was really an eye-opener at that age, thirteen, fourteen. We collected the money. There were two guys and a little electric car, and on Saturday and Sunday it’s me with them trying to screw the money out. And I realized I was there as an extra, a lookout, while they say, “Mrs. X… it’s been two weeks now.” Sometimes I’d sit in the truck, freezing cold and waiting, and then after twenty minutes the baker would come out red faced and doing his flies up. I started slowly to realize how things were paid for. And then there were certain old ladies who were obviously so bored, the highlight of their week was being visited by the bread men. And they’d serve the cakes they’d bought from us, have a nice cup of tea, sit around and chat, and you realize you’ve been there a bloody hour and it’s going to be dark before you finish the round. In the winter I looked forward to them, because it was kind of like

Arsenic and Old Lace,

these old ladies living in a totally different world.

While I was practicing my knots I wasn’t noticing—in fact I didn’t piece it together until years later—some swift moves Doris was making. Around 1957, Doris took up with Bill, now Richards, my stepfather. He married Doris in 1998, after living with her since 1963. He was in his twenties and she was in her forties. I just remember that Bill was always there. He was a taxi driver, and he was always driving us about, always willing to take on anything that involved driving. He even drove us on holiday, me, Mum and Dad. I was too young to know what the relationship was. Bill to me was just like Uncle Bill. I didn’t know what Bert thought and I still don’t know. I thought Bill was Bert’s friend, a friend of the family.

He just turned up and he had a car. That’s partly what did it for Doris, back in 1957. Bill had first met her and me in 1947, when he lived opposite us in Chastilian Road, working in the Co-op. Then he joined a firm of taxi drivers and didn’t reappear until Doris came out of Dartford station one day and saw him. Or, as Doris told it, “I only knew him from living opposite him, and he was at the cab one day, and I came off the station and I went, ‘Hello.’ And he came running after me and said, ‘I’ll take you home.’ I said, ‘Well, I don’t mind,’ because I would have had to wait for a bus otherwise, and he took me home. And then it started and I can’t believe it. I was so brazen.”

Bill and Doris had to get up to some deception, and I feel for Bert if he knew. One of their opportunities was Bert’s passion for tennis. It left Doris and Bill free to have a date out together. Then, according to Bill, they’d somehow get in a position to see Bert leaving the tennis club on his bike and race back in Bill’s taxi to get Doris home before him. Doris reminisced, “When Keith started with the Stones, Bill used to take him here and everywhere. If it wasn’t for Bill, he couldn’t have gone anywhere. Because Keith used to say, ‘Mick says I’ve got to get to so-and-so.’ And I’d say, ‘How are you going to get there, then?’ And Bill would say, ‘I’ll take him.’ ” That’s Bill’s so far unheralded role in the birth of the Rolling Stones.

Still, my dad was my dad, and I was scared shitless of facing him come the day I got expelled, which is why it had to be a long-term campaign—it couldn’t be done in one swift blow. I would just slowly have to build up the bad marks until they realized that the moment had come. I was scared not from any physical threat, just of his disapproval, because he’d send you to Coventry. And suddenly you’re on your own. Not talking to me or even recognizing I was around was his form of discipline. There was nothing to follow it up; he wasn’t going to whip my arse or anything like that; it never came into the equation. The thought of upsetting my dad still makes me cry now. Not living up to his expectations would devastate me.

Once you’d been shunned like that you didn’t want it to happen again. You felt like you were nothing, you didn’t exist. He’d say, “Well, we ain’t going up the heath tomorrow”—on the weekend we used to go up there and kick a football about. When I found out how Bert’s dad treated him, I thought I was very lucky, because Bert never used physical punishment on me at all. He was not one to express his emotions. Which I’m thankful for in a way. Some of the times I pissed him off, if he had been that kind of guy, I’d have been getting beatings, like most of the other kids around me at that time. My mum was the only one that laid a hand on me now and again, round the back of the legs, and I deserved it. But I never lived in fear of corporal punishment. It was psychological. Even after a twenty-year gap, when I hadn’t seen Bert for all that time and when I was preparing for our historic reunion, I was still scared of that. He had a lot to disapprove of in the intervening twenty years. But that’s a later story.

The final action that got me expelled was when Terry and I decided not to go to assembly on the last day of the school year. We’d been to so many and we wanted to have a smoke, so we just didn’t go. And that I believe was the actual final nail in the coffin of getting me expelled. At which of course my dad nearly blew up. But by then, I think he’d written me off as any use to society. Because by then I was playing guitar, and Bert wasn’t artistically minded and the only thing I’m good at is music and art.

The person I have to thank at this point—who saved me from the dung heap, from serial relegation—is the fabulous art instructor Mrs. Mountjoy. She put in a good word for me to the headmaster. They were going to dump me onto the labor exchange, and the headmaster asked, “What’s he good at?” “Well, he can draw.” And so I went to Sidcup Art College, class of 1959—the musical intake.

Bert didn’t take it well. “Get a solid job.” “What, like making lightbulbs, Dad?” And I started to get sarcastic with him. I wish I hadn’t. “Making valves and lightbulbs?”

By then I had big ideas, even though I had no idea how to put them into operation. That required meeting a few other people later on. I just felt that I was smart enough, one way or another, to wriggle out of this social net and playing the game. My parents were brought up in the Depression, when if you got something, you just kept it and you held it and that was it. Bert was the most unambitious man in the world. Meanwhile, I was a kid and I didn’t even know what ambition meant. I just felt the constraints. The society and everything I was growing up in was just too small for me. Maybe it was just teenage testosterone and angst, but I knew I had to look for a way out.

In which I go to art college, which is my guitar school. I play in public for the first time and end up with a chick that same night. I meet Mick at Dartford Railway Station with his Chuck Berry records. We start playing—Little Boy Blue and the Blue Boys. We meet Brian Jones at the Ealing Club. I get Ian Stewart’s approval at the Bricklayers Arms, and the Stones form around him. We want Charlie Watts to join but can’t afford him.

I

don’t know what would have happened if I

hadn’t

been expelled from Dartford and sent to art college. There was a lot more music than art going on at Sidcup, or any of the other art colleges in south London that were turning out suburban beatniks—which is what I was learning to be. In fact there was almost no “art” to be had at Sidcup Art College. After a while you got the drift of what you were being trained for, and it wasn’t Leonardo da Vinci. Loads of flash little sons of bitches would come down in their bow ties from J. Walter Thompson or one of the other big advertisers for one day a week to take the piss out of the art school students and try and pick up the chicks. They’d lord it over us and you got taught how to advertise.

There was a great feeling of freedom when I first went to Sidcup. “You mean you can actually smoke?” You’re with lots of different artists, even if they’re not really artists. Different attitudes, which was really important to me. Some are eccentrics, some are wannabes, but they’re an interesting bunch of people, and a very different breed, thank God, to what I was used to. We’d all got there out of boys’ schools and suddenly we’re in classes with chicks. Everybody’s hair was getting long, mainly because you could, you were that age and for some reason it felt good. And you could finally dress any way you wanted; everybody had come from uniforms. You actually looked forward to getting on the train to Sidcup in the morning. You actually looked forward to it. At Sidcup I was “Ricky.”

I realize now that we were getting some dilapidated tail end of a noble art-teaching tradition from the prewar period—etching, stone lithographs, classes on the spectrum of light—all thrown away on advertising Gilbey’s gin. Very interesting, and since I liked drawing anyway, it was great. I was learning a few things. You didn’t realize you were actually being processed into some sort of so-called graphic designer, probably Letraset setter, but that came later. The art tradition staggered on under the guidance of burnt-out idealists like the life classes teacher, Mr. Stone, who had been trained at the Royal Academy. Every lunchtime he’d down several pints of Guinness at the Black Horse and come to class very late and very pissed, wearing sandals with no socks, winter and summer. Life class was often hilariously funny. Some lovely old fat Sidcup lady with her clothes off—oooh way hay tits!—and the air heavy with Guinness breath and a swaying teacher hanging on to your stool. In homage to high art and the avant-garde that the faculty aspired to, one of the school photographs designed by the principal had us arranged like figures in a geometric garden from the big scene in

Last Year at Marienbad,

the Alain Resnais film—the height of existentialist cool and pretentiousness.

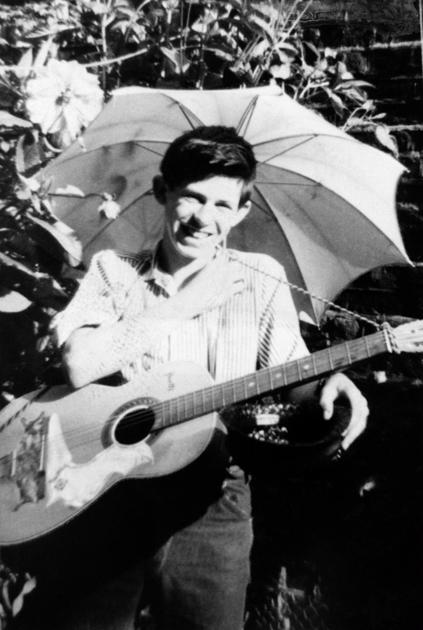

It was a pretty lax routine. You did your classes, finished your projects and went to the john, where there was this little hangout-cloakroom, where we sat around and played guitar. That was what really gave me the impetus to play, and at that age you pick up stuff at speed. There were loads of people playing guitar there. The art colleges produced some notable pickers in that period when rock and roll, UK-style, was getting under way. It was a kind of guitar workshop, basically all folk music, Jack Elliott stuff. Nobody noticed if you weren’t at the college, so the local musical fraternity used it as a meeting place. Wizz Jones used to drop in, with a Jesus haircut and a beard. Great folk picker, great guitar picker, who’s still playing—I see ads for his gigs and he looks similar, though the beard’s gone. We barely met, but Wizz Jones to me then was like… Wizzzz. I mean, this guy played in clubs, he was on the folk circuit. He got paid! He played pro and we were just playing in the toilet. I think I learned “Cocaine” from him—the song and that crucial fingerpicking lick of the period, not the dope. Nobody, but nobody played that South Carolina style. He got “Cocaine” from Jack Elliott, but a long time before anyone else, and Jack Elliott had got it from the Reverend Gary Davis in Harlem. Wizz Jones was a watched man, watched by Clapton and Jimmy Page at the time too, so they say.

I was known in the john for my rendition of “I’m Left, You’re Right, She’s Gone.” They sometimes got at me because I still liked Elvis at the time, and Buddy Holly, and they didn’t understand how I could possibly be an art student and be into blues and jazz and have anything to do with that. There was this certain “Don’t go there” with rock and roll, glossy photographs and silly suits. But it was just music to me. It was very hierarchical. It was mods and rockers time. There were clear-drawn lines between the “beats,” who were addicted to the English version of Dixieland jazz (known as traditional), and those into R&B. I did cross the line for Linda Poitier, an outstanding beauty who wore a long black sweater, black stockings and heavy eyeliner à la Juliette Gréco. I put up with a lot of Acker Bilk—the trad jazzers’ pinup—just to watch her dance. There was another Linda, specs, skinny but beauty in the eyes, who I clumsily courted. A sweet kiss. Strange. Sometimes a kiss is burned into you far more than whatever comes later. Celia I met at a Ken Colyer Club all-nighter. She was from Isleworth. We hung all night, we did nothing, but for that brief moment it was love. Pure and simple. She lived in a detached house, outta my league.

S

ometimes

I

still visited

G

us.

By that time, because I’d been playing for two or three years, he said, “Come on, give me ‘Malagueña.’ ” I played it for him and he said, “You’ve got it.” And then I started to improvise, because it’s a guitar exercise. And he said, “That’s not how it goes!” And I said, “No, but Granddad, it’s how it

could

go.” “You’re getting the hang of it.”

In fact, early on I was never really that interested in being a guitar player. It was just a means to an end to produce sound. As I went on I got more and more interested in the actual playing of guitar and the actual notes. I firmly believe if you want to be a guitar player, you better start on acoustic and then graduate to electric. Don’t think you’re going to be Townshend or Hendrix just because you can go

wee wee wah wah,

and all the electronic tricks of the trade. First you’ve got to know that fucker. And you go to bed with it. If there’s no babe around, you sleep with it. She’s just the right shape.

I

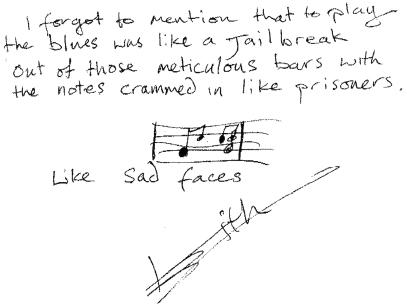

’ve learned everything

I know off of records. Being able to replay something immediately without all that terrible stricture of written music, the prison of those bars, those five lines. Being able to hear recorded music freed up loads of musicians that couldn’t necessarily afford to learn to read or write music, like me. Before 1900, you’ve got Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Chopin, the cancan. With recording, it was emancipation for the people. As long as you or somebody around you could afford a machine, suddenly you could hear music made by people, not set-up rigs and symphony orchestras. You could actually listen to what people were saying, almost off the cuff. Some of it can be a load of rubbish, but some of it was really good. It was the emancipation of music. Otherwise you’d have had to go to a concert hall, and how many people could afford that? It surely can’t be any coincidence that jazz and blues started to take over the world the minute recording started, within a few years, just like that. The blues is universal, which is why it’s still around. Just the expression and the feel of it came in because of recording. It was like opening the audio curtains. And available, and cheap. It’s not just locked into one community here and one community there and the twain shall never meet. And of course that breeds another totally different kind of musician, in a generation. I don’t need this paper. I’m going to play it straight from the ear, straight from here, straight from the heart to the fingers. Nobody has to turn the pages.

Everything was available in Sidcup—it reflected that incredible explosion of music, of music as style, of love of Americana. I would raid the public library for books about America. There were people who liked folk music, modern jazz, trad jazz, people who liked bluesy stuff, so you’re hearing prototype soul. All those influences were there. And there were the seminal sounds—the tablets of stone, heard for the first time. There was Muddy. There was Howlin’ Wolf’s “Smokestack Lightnin’,” Lightnin’ Hopkins. And there was a record called

Rhythm & Blues Vol.

1. It had Buddy Guy on it doing “First Time I Met the Blues”; it had a Little Walter track. I didn’t know Chuck Berry was black for two years after I first heard his music, and this obviously long before I saw the film that drove a thousand musicians —

Jazz on a Summer’s Day,

in which he played “Sweet Little Sixteen.” And for ages I didn’t know Jerry Lee Lewis was white. You didn’t see their pictures if they had something in the top ten in America. The only faces I knew were Elvis, Buddy Holly and Fats Domino. It was hardly important. It was the sound that was important. And when I first heard “Heartbreak Hotel,” it wasn’t that I suddenly wanted to be Elvis Presley. I had no idea who he was at the time. It was just the sound, the use of a different way of recording. The recording, as I discovered, of that visionary Sam Phillips of Sun Records. The use of echo. No extraneous additions. You felt you were in the room with them, that you were just listening to exactly what went down in the studio, no frills, no nothing, no pastry. That was hugely influential for me.

T

hat

E

lvis

LP

had

all the Sun stuff, with a couple of RCA jobs on it too. It was everything from “That’s All Right,” “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” “Milk Cow Blues Boogie.” I mean, for a guitar player, or a budding guitar player, heaven. But on the other hand, what the hell’s going on there? I might not have wanted to be Elvis, but I wasn’t so sure about Scotty Moore. Scotty Moore was my icon. He was Elvis’s guitar player, on all the Sun Records stuff. He’s on “Mystery Train,” he’s on “Baby Let’s Play House.” Now I know the man, I’ve played with him. I know the band. But back then, just being able to get through “I’m Left, You’re Right, She’s Gone,” that was the epitome of guitar playing. And then “Mystery Train” and “Money Honey.” I’d have died and gone to heaven just to play like that. How the hell was that done? That’s the stuff I first brought to the john at Sidcup, playing a borrowed f-hole archtop Höfner. That was before the music led me back into the roots of Elvis and Buddy—back to the blues.

To this day there’s a Scotty Moore lick I still can’t get down and he won’t tell me. Forty-nine years it’s eluded me. He claims he can’t remember the one I’m talking about. It’s not that he won’t show me; he says, “I don’t know which one you mean.” It’s on “I’m Left, You’re Right, She’s Gone.” I think it’s in E major. He has a rundown when it hits the 5 chord, the B down to the A down to the E, which is like a yodeling sort of thing, which I’ve never been quite able to figure. It’s also on “Baby Let’s Play House.” When you get to “But don’t you be nobody’s fool / Now baby, come back, baby…” and right at that last line, the lick is in there. It’s probably some simple trick. But it goes too fast, and also there’s a bunch of notes involved: which finger moves and which one doesn’t? I’ve never heard anybody else pull it off. Creedence Clearwater got a version of that song down, but when it comes to that move, no. And Scotty’s a sly dog. He’s very dry. “Hey, youngster, you’ve got time to figure it out.” Every time I see him, it’s “Learnt that lick yet?”

T

he hippest guy

at Sidcup Art College was Dave Chaston, a famous man of that time and place. Even Charlie Watts knew Dave, in some other jazz connection. He was the arbiter of hip, hip beyond bohemian, so cool he could run the record player. You’d get a 45 and play it and play it, again and again, almost like looping it. He had the first Ray Charles before anybody else—he’d even seen him play—and I first heard him during one of those lunchtime record breaks.