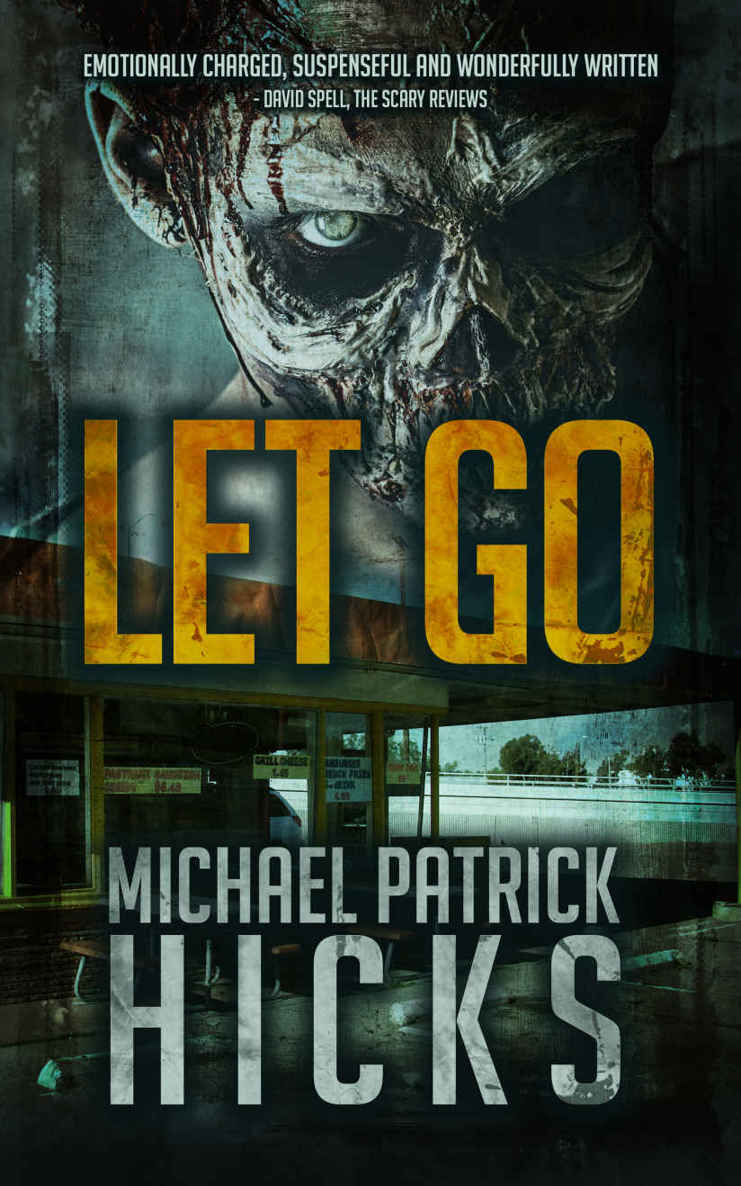

Let Go

Authors: Michael Patrick Hicks

Copyright © 2016 Michael Patrick Hicks

All rights reserved.

http://www.michaelpatrickhicks.com

Newsletter:

http://bit.ly/1H8slIg

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of the author, except where permitted by law.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

To stay up to date on Michael’s latest releases, and receive advanced reader copies of his work, join his newsletter, memFeed:

http://bit.ly/1H8slIg

Website:

http://michaelpatrickhicks.com

E-mail:

[email protected]

Facebook:

http://www.facebook.com/authormichaelpatrickhicks

twitter:

http://www.twitter.com/MikeH5856

About

Let Go

Widowed and with retirement drawing near, Everett Hart believes he has already lost everything - until the dead begin to rise.

Trapped in a cheap restaurant with a small band of other elderly survivors, Everett is forced to decide if he’ll fight for whatever scraps of a future remain, or if he will simply… let go.

Let Go

is a short story of approximately 10,000 words.

LET GO

Michael Patrick Hicks

Everett Hart hadn’t set foot inside Brown’s Fish & Chips in three years, not since his wife, Lucille, had died from breast cancer. When she was alive, they’d been regulars at the joint, coming every Sunday evening except during Lent, when they came on Fridays, which was when Brown’s was at its busiest. Getting a table had often come with a long wait, regulars or not.

Brown’s had been a staple in their relationship for going on twenty years, and it had seemed to Everett that the family-owned restaurant would always be there, same as his Lucille. She was gone; the restaurant remained.

Little had changed about the small restaurant. At the front was a glass display case with the counter on top, empty save for the single wooden shelf that divided its interior, with room enough for two cash registers, although he could only recall ever seeing one of them manned, even during peak Lent hours. Two walls of the dining room were lined with a row of brown vinyl booths, the upholstery shiny and spiderwebbed with white lines and the occasional crack where the stuffing hemorrhaged its way out. In between were blue Formica tables with four chairs, the metal rimming polished and bright beneath the overhead lighting. Everything about the restaurant screamed “relic,” Everett included.

The walls were unadorned, save for a single clock mounted at the front over the glass display case.

Unassuming, maybe even dull, Brown’s attracted the elderly, primarily, thanks to its cheap food and barren interior, although families and children were certainly welcome and occasionally even seen.

Everett did not consider himself elderly, even if retirement was fast approaching and he had his AARP card. He was well aware that death was close and that his birth was a quaint, forgotten notion that could only be smiled at, even if just with a meaningless, wistful smile. Lucille’s passing had made that abundantly clear, more so than his hair loss—and the whitening of what little hair remained—and all the damnable wrinkles that marred his face and body.

“What can I getcha?” the waitress asked. She appeared roughly five minutes after a young Mexican boy had come to fill his water glass, not that Everett was logging the minutes. He didn’t mind waiting and revisiting old phantoms.

Everett hadn’t bothered looking at the menu. There was no need; he always ordered the same. “Fried perch. Coleslaw. Fries.”

“You got it, hon,” she said, making a quick scribble on the order pad and sauntering away.

She looked like that waitress from

Alice

, he thought. Her hair was a miniature peroxide-blond beehive, and her uniform was brown. She was larger, too, and older. And maybe she didn’t look all that much like that one from

Alice

after all.

I think you’re thinking of Mama, from

Mama’s Family, Lucille said from inside his head.

You know, I think you’re right, hon.

The waitress’s name tag said Maddie, and she had a big caboose that he watched with morbid fascination as it swung side to side with each step toward the rear of the dining room, to the swinging door that must have led to the kitchen. He caught a brief glimpse of activity beyond, bodies hustling back and forth.

He sat facing the inside of the restaurant because Lucille had always liked to take the seat facing the door and the front window. She was a people watcher and had always been oddly absorbed by who was coming in. Back then, he and Lucille had probably been the youngest customers Brown’s had ever seen.

Lucille’s parents had introduced them to the place. It had been her father’s eightieth birthday—his last, as it happened—but the food had been good enough that they came back once in a while when neither felt like cooking. “Once in a while” turned into once a month, and that had turned into once a week.

Lucille watched the people, occasionally commenting to him on who was coming or going. He would listen attentively, sipping ice water with a wedge of lemon squeezed into it. A bowl of lemon slices for the fish always sat on every tabletop, and he always added lemon to his water, too. As the years slipped by, he began bringing a newspaper with him, hoping to stay up on current events, and she brought a book, and their table grew a bit quieter, their conversations and her observations a little less frequent. After nearly forty years together, how much did they have left to say?

If you were here right now, I’d be talking your ear off

, he thought, imagining Lucille across from him. Even when they sat in companionable silence, reading, they always had a hand stretched across the table, breaking their hold only when necessary to turn a page, but their fingers always found one another again and settled into that familiar, reassuring squeeze.

Newspapers were too hard to read anymore, the print too small. And the world events always seemed to be so much the same with murder, wars, corruption, drone strikes, an unending pantheon of misery and finger-pointing and brutality. He didn’t need that.

Instead, he read on an electronic tablet, losing himself in fiction. Stuff Lucille, a horror hound, would have enjoyed. Some of it he enjoyed in spite of himself. It was mindless entertainment, junk food for the brain, and Jesus, he could almost hear his mother’s voice speaking those words. His son, William, had gotten the tablet for him two years ago, and he had learned how to increase the font size so he could read without his glasses.

He read more now than ever before. What else was he going to do? The kid was out of the house, and his wife was in the ground. TV bored him, and with his books, he could always make a mental movie if the words were good enough.

Since getting the Kindle, he’d bought most of Lucille’s books in digital form—the type in the print editions she had owned, like that in newspapers, was too tiny for his tired old eyes. He now had a healthy library of titles by Brian Keene, Joe Lansdale, and Jonathan Maberry, from Ania Ahlborn to Stephen King—of course—and so many more he could hardly recall all the names populating his digital shelf space.

As his eyes drifted over the scattering of old folks at the other tables, Lucille’s voice piped up again.

She’s got a sort of Jacqueline Kennedy vibe about her.

It’s the pillbox hat

, Everett replied. Looking toward the woman’s partner, a weathered black man in a blue windbreaker, he asked,

What about him?

He looks like Ossie Davis

, she said.

They were illicit lovers once upon a time

, she added with surety and because she always had a story about the people she saw.

Really?

Yup,

she said.

She was a reverend’s daughter and they started dating young, and when she got pregnant and then lost the baby it caused all sorts of controversy in that small rinky-dink town they were from.

He fought in one of the wars, Korea probably, and gave more to his country than he ever got back, that’s for sure. But she waited for him to come back home, and when he did they came north, settled here in this little town and made a home.

He found a job as a car salesman, but not one of those slimy used car salesmen you always hear about. No, he was one of the good ones, as honest as he could be and still cut a commission, fair and decent. She was a purebred housewife, maybe did some medical billing from home to help make ends meet. She was never able to have kids, and she went through a few miscarriages before they figured out it wasn’t ever meant to be.

They love each other, though, a lot, and they’re happy together. You can see it in their eyes, how they look at one another even after all these years. Ain’t that something?

Had she been there, she would have taken a long drink of water, a certain sparkle in her eyes as they drifted over the other people, seeking more stories.

He had always wondered where she came up with those stories, and regretted that he could never recapture their magic. He tried, though, simply so he could imagine her voice, and even as he looked over the other diners he knew he was tapped out, with no more stories to tell.

Everett shifted his weight then took out his Kindle and resumed reading a Joe Hill novel while he waited for his fried perch. A few minutes later, the waitress came with a plate of hot buttered rolls, and he took one to nibble on. Mostly, he just needed something warm to occupy his free hand.

Lucille would have loved a Kindle, he knew. They’d have been able to read and hold hands and never let go to turn the page.

But he also knew that, eventually, one of them would have had to let go.

When his food arrived, he put the Kindle to sleep and closed its magnetic cover before placing it back in his coat pocket, the pocket with the gun. He folded his coat in half, burying that pocket, and turned his attention to the fish.

He savored the crunch of the crusty golden beer batter, and after the first bite, he squeezed a lemon wedge over the four filets. Even better, he mused. Satisfied, he reached for the ketchup set up alongside a greenish bottle of vinegar at the end of the table, against the wall. He spent a long time squeezing the bottle, piling ketchup into a tall hill beside the fries. He was saving the coleslaw, served in its own small bowl beside the plate, for last. He had always loved coleslaw, and Brown’s made it just right. None of that vinegar base. This was all mayo, perfectly balanced and nicely chilled, the perfect endnote to the meal.

God, he wished Lucille were here. He wished they’d been able to come back together one last time, before the chemo destroyed her appetite and the cancer finally ate her up.

Since her death, food had become tasteless. No longer a thing of joy, eating had become another part of the daily grind, just some manufactured nutrients and chemical energy. He stopped cooking because with only him in the house, what was the point? He ate from boxes, all mass-produced stuff and mostly from the freezer and cereal aisles. This plate of fried perch was the first meal he had actually enjoyed in more than three years, and that, he knew, was mostly because he imagined Lucille across from him, enjoying her food, always a duplicate order of his.

“How about some dessert?” the waitress, Maddie, asked as he polished off the fish and spat out an errant lemon seed.

A police siren roared outside, the cop car screaming past. Everett and Maddie turned to look, although from his spot inside the booth, he couldn’t see the car. Besides, by the time he got himself situated to see around the corner of the high-backed seat, the car was long gone.

“No, thank you,” he said.

“When you’re ready, then.” She left a green bill holder on the table and scooted away.

Another siren wailed past, and then a third. Maybe more, judging by the volume of the noise, which was loud and sounded as though the car had stopped nearby.