Laughter in Ancient Rome (19 page)

Read Laughter in Ancient Rome Online

Authors: Mary Beard

THE ROMAN SIDE OF GREEK LAUGHTER

Classicists have long tussled with the ways that Roman writers reinvigorate (or recycle) their Greek predecessors, pointing to a characteristic combination of similarity and difference found throughout Roman (re)-use of Greek cultural forms, right down to the laughs. But they more rarely look at the relationship from the other side. To conclude this chapter, and to think more about potential “Roman” aspects of “Greek” laughter, I am taking a cue from Andrew Wallace-Hadrill and from Tony Spawforth, who have both argued for a wide-ranging cultural impact of Rome on the Greek world (from the style of lamps made in Roman Athens to the “cultural comportment” of the imperial Greek elite).

77

Some of the traditions often assumed to be those of classical Greece owe a lot in various ways to the cultural conversations of the (Greco-)Roman Empire.

One of the most memorable symbols of Greek laughter is the fifth-century BCE philosopher Democritus, from the northern Greek city of Abdera—who has gone down in history as “the laughing philosopher,” celebrated in that role not only in antiquity but also by modern artists and writers as diverse as Peter Paul Rubens and Samuel Beckett. Often paired with Heraclitus (his opposite—“the weeping philosopher”), Democritus crops us time and again in ancient writing in his iconic role as “the laugher” (or as the “laughter expert”).

78

When, for example, Cicero is settling down in

On the Orator

to a discussion of the role of laughter in oratory and wants to brush aside the impossible question of what laughter actually is, he writes, “We can leave that to Democritus”;

79

others tell how Democritus’ mockery of his fellow countrymen gave him the nickname Laughing Mouth or made him, as Stephen Halliwell has put it, the “patron saint” of satiric wit (“Democritus used to shake his sides in perpetual laughter,” wrote Juvenal, even though there was much less in his day to provoke ridicule—no flummery, no togas with purple stripes or sedan chairs).

80

But by far the richest account of Democritus’ laughter is found in what is, in effect, an epistolary novella comprising a series of fictional letters written in Greek, exchanged between the citizens of Abdera and the legendary Greek doctor Hippocrates—now preserved among the writings associated with Hippocrates (spuriously, in the sense that almost certainly none are from his own hand).

81

In this story, the Abderites (who have their own cameo part to play in the history of laughing and joking, as we shall see in chapter 8) are increasingly concerned about the sanity of their famous philosopher, for the simple reason that he was always laughing, and at the most inappropriate things. “Someone marries, a man goes on a trading venture, a man gives a public speech, another takes an office, goes on an embassy, votes, is ill, is wounded, dies. He laughs at every one of them,”

82

they write in their exasperation to Hippocrates, asking him to come to Abdera to cure Democritus. The doctor agrees (and the novella includes some comic touches among the preparations—from transportation to arrangements for his wife during his absence). But as we learn from the letters, when he encounters the patient, he soon discovers that Democritus is not mad at all: he is rightly laughing at the folly of humanity (“You think there are two causes of my laughter—good things and bad things. But I laugh at one thing—mankind”

83

).

En route to this (happy) conclusion, there is plenty of opportunity for the various parties to offer their views of what laughter is for. In fact, the novella is one of the most extended philosophical treatments of laughter to survive from the ancient world. But what I want to underline here is that there is no evidence whatsoever for any particular association between Democritus and laughter before the Roman period. The earliest reference we have to this connection is that casual aside in Cicero, while the Hippocratic novella is almost certainly to be dated to the first century CE, several centuries after the deaths of both of its protagonists.

84

Democritus’ own writing, so far as we can reconstruct it, was principally concerned with theories of atomism and a much more moderate ethical stance than the “absurdist” position that the novella implies. How or why he had been resymbolized by the first century CE in these very different terms, we can only conjecture.

We find a broadly similar pattern in another significant symbol of Greek laughter—that is, the tradition of distinctively “Spartan” laughter. Sparta is the only city in the ancient world, outside the realm of fiction (see pp. 181–83), where there was said to have been a statue, even a shrine and a religious cult, of Laughter; it was attributed to the mythical lawgiver Lycurgus.

85

Moreover, the boot-camp atmosphere of classical Sparta is supposed to have included a prominent role for laughing and jesting. The young Spartiates were said to learn both to jest and to endure jesting in their “common messes” (

sussitia

), and the Spartan women were supposed to ridicule those young men who failed to meet the standards of the training system.

86

The surviving references to Spartan quips and witticisms emphasize their down-to-earth frankness, even aggression (such as the retort of the lame Spartan fighter who was laughed at by his peers: “Idiots, you don’t need to run away when you fight the enemy”

87

). Tempting as it may be to use this evidence to fill in some of the many gaps in what we know of classical (fifth- and fourth-century BCE) Spartan culture,

88

the fact is that it all comes from writers of Roman date—principally, but not only, Plutarch. It must in part reflect a nostalgic construction of Spartan “exceptionalism,” with these supposed “primitive” traditions of laughter being used, retrospectively, to mark out the oddity of the Spartan system.

89

Of course, in both these cases we should be careful not to overclaim. We would get a very odd view of ancient history if we assumed that no traditions existed before the first surviving reference to them (“absence of evidence is not evidence of absence,” as the old inferential cliché goes). It would be implausible to imagine that, in his casual aside, Cicero invented Democritus’ connection with laughter; much more likely he was referring (with what degree of knowledge is not clear) to some preexisting commonplace. On the evidence we have, it is impossible to be certain exactly when the popular metamorphosis of Democritus—from atomist to laugher—took place.

90

There is certainly a deeper prehistory to the traditions of Spartan laughter too: Plutarch, in fact, cites a third-century BCE source for the “shrine of Laughter,” and many of those anecdotal quips attributed to famous Spartans of the past may well have had an even earlier origin.

91

Yet the fact remains that—selected, adjusted, and embellished as they must have been—the traditions about Democritus and the Spartans have come down to us in the literature of the Roman Empire. In a scholarly world in which historians have tried to push so many traditions back to the glory days of classical Greece, it is important to remember that many of the details, the interrelationships, the cultural nuances (even if not the entire traditions themselves) are the product of the Greco-Roman imperial world.

One final example gives us a nice glimpse of the two-way traffic in “laughter culture”—not only from Greece to Rome but also from Rome to Greece. One of the slogans of British eighteenth-century urbanity was “Attic salt”—the traditions of elegant wit particularly associated with ancient Athens. The same Lord Chesterfield who so disdained “audible laughter” was a tremendous advocate of this particular style of jest, as he wrote to his long-suffering son: “That same Attic salt seasoned almost all Greece, except Boeotia; and a great deal of it was exported afterward to Rome, where it was counterfeited by a composition called Urbanity, which in some time was brought to very near the perfection of the original Attic salt. The more you are powdered with these two kinds of salt, the better you will keep, and the more you will be relished.”

92

Poor Lord Chesterfield could not have been more wrong in his chronology, or in suggesting the transmission of “Attic salt” from Greece to Rome. It is true that Roman writers admired Athenian wit: they saw it as a form to be imitated, and in their cultural geography of wit they put the Athenians in prize position, followed by the Sicilians and then the Rhodians.

93

But so far as we can tell, the idea of wit as salt (

sal

) was originally a Roman idea, defined in Latin and part of a range of Roman cultural tropes that (as we shall see) linked jesting and laughing to the sphere of dining and the repertoire of cooking. “Attic salt” was not a Greek term, but it was the Romans’ way of describing their own construction of Athenian wit.

No Athenians, so far as we know, ever congratulated themselves on their “Attic salt.” In classical Greece, the word

hals

(salt) was not part of the terminology of jesting. Eventually, however, the idea did spread eastward. Some Greeks of the Roman period apparently adopted, incorporated, and maybe adjusted this characteristically “Roman” perspective on laughter. In the second century CE, we find Plutarch referring to the wit of Aristophanes and Menander as

hales

—their “little pinches of salt.”

94

We should make sure not to underestimate the Roman aspects of that often inextricable mixture that is the Greco-Roman culture of laughter.

• • •

It is to various aspects of that inextricable mixture that we now turn. The issues that I have been discussing in these first four chapters underlie the explorations in the second part of this book of particular aspects of Roman laughter and of some of the distinctive characters who have a particular role to play in the “laughterhood” of Rome. We shall encounter laughing emperors, plenty of monkey business, and some passable jokes—but first the funniest man in the Roman world, Marcus Tullius Cicero, and some of his fellow orators. There have been several excellent studies of uses of wit and laughter in the Roman courtroom, but I shall focus on the dilemmas confronting the joking orator trying to raise a laugh from his audience in order to expose some of the ambiguities and anxieties of the culture of laughter in ancient Rome.

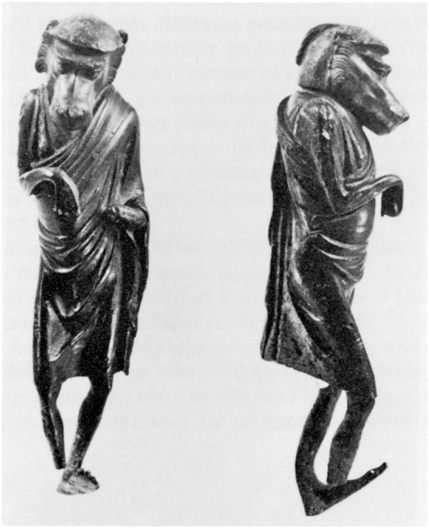

FIGURE 1.

Frans Hals,

The Laughing Cavalier

(1624). This painting—which we now take for granted as an image of a laughing man—raises the question of how confidently we can identify laughter in the art of the past.

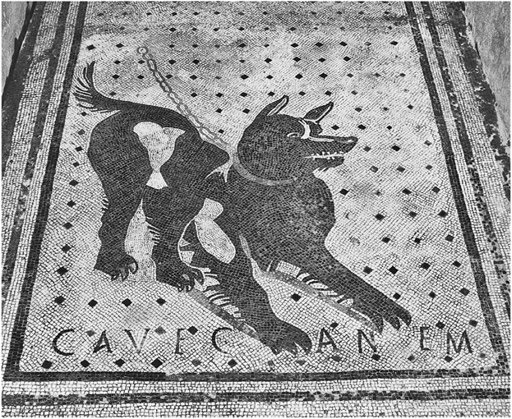

FIGURE 2.

Mosaic—“Beware of the dog”—from the House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii (first century CE). How can we decide if this image was intended to make visitors laugh?