Las Christmas (21 page)

My father changed tactics. He mellowed his voice yet maintained a firm position: “Mariana please, don't insist. You know I can't stand your sisters. I'm reminded of them all the time at work. Do I also have to deal with them during Christmas Eve?”

“And that is how you thank them, after all they have done for us?”

“We have earned what we have. We owe nothing to them.”

“Come on Juan, you know that's not entirely true.”

“Look, Mariana, I'd rather die than spend a night listening to their shouts and tending their parties.” He raised his voice, visibly angry. “Who would imagine! Those sisters of yours, so well dressed, such professionals. But put on a record and open a bottle of rum in front of them. What a show! They can't wait to make fools of themselvesâ”

“Why do you have to talk about my sisters like that?” my mother's voice was sad, but her eyes were getting fiercer and fiercer by the minute. It was hard to believe Dad did not notice her eyes. All he had to do was look in the mirror.

“Papi, stop talking,” I muttered. “Stop talking before Mom cuts you with her eyes . . .” But he wouldn't listen. I muttered and muttered, “Stop it, Dad, stop it,” very softly, wishing I could use my persuasion skills right then, wishing to have telepathic powers, wishing my banana-flavored lip gloss could turn into a secret microphone through which I could warn my father about my mother's eyes. But he kept on.

“I'm telling the truth. Those sisters of yours are insufferable. And you defend them as ifâ”

“They're my sisters!” my mother screamed. Mom pulled off her hair rollers, threw them all over the place. She sprinted to the bedroom, found my brother's lost shoe and pushed it onto his foot while she continued screaming, “I'm tired of this shit. All I wanted was to have a good time with my entire family. Is that too much to ask?” She finished dressing Juan Carlos so fast that before I knew it he was standing in the middle of the corridor all combed, dressed and perfumed. “If you don't want to go, there are other ways of saying it. Why do you have to try and fuck up my Christmas?”

“Don't talk dirty in front of the kids,” my father yelled.

“I talk dirty all I want!” she screamed and stormed out the door, my brother and I trailing behind. My father just stood there, his arms limp and a blank expression on his face.

My mother's eyes were watery when she opened her Volkswagen. The Volky was blue and shiny and smelled of pine trees, just like Christmas. But we were gloomy and nervous as she pushed us in and drove to Grandma's house. Juan Carlos constantly looked at me, his older sister, as if I had a clue about what we should do next. He expected me to tell him if we should try and console Mom or speak on behalf of our father or jump out of the car to create a crisis that could bring them together again. But what did I know? Why should I be caught in the middle of the drama? All for a stupid party on stupid Christmas Eve at stupid Don Agapito's house.

We arrived at Grandma's. All the sisters were there, the traditional food cooked and served. The musicians began to arrive with their cables, switches, and instrument cases. Everything was happiness and joy, but we were a wreck. My heart was pounding. My brother looked like he would burst into tears at any moment. My mother tried to greet her sisters and neighbors, but her smile came out crooked, stale. I don't remember if our Christmas Eve dinner was good that year, most probably because I didn't eat a bite.

We finished dinner in silence, and sat on Grandma's veranda to watch the musicians prepare their instruments in Don Agapito's terrace. We could see the musicians connecting extensions and testing microphones through the ornamental blocks that separated the terrace from our veranda. Don Benny's huge belly showed between the buttons of his striped shirt, and when he bent over to find the right cables for the amplifier we could see his butt. “Look at Don Benny's piggy bank,” my cousins Mayrita and Astrid giggled, pointing at the pale pasty flesh overflowing his pants. At a distance, the hors d'oeuvres trays showed neat patterns of food on a table by the bar. My aunts Cuca and Cusita had carefully arranged the table before we arrived. “To entertain ourselves,” Titi Cusita explained. “After we finished Mami's hair, Cuca and I had all this time on our hands.”

That night, the air felt fresh and humid, the streets were a little damp from afternoon showers, and the air smelled of ocean spray and orange blossoms from the tree in Grandma's veranda. Soon, the music started playing next door. We got up and helped Grandma look for her glasses and her false teeth and her keys. Once we arrived at Don Agapito's, my mother sat in a corner, drinking a glass of beer. She was shy, a little depressed. Titi Cuchira and Titi Cruzjosefa tried to cheer her up.

“

Muchacha,

olvÃdate de ese tipo.

Don't let him spoil your night. Here, have some

coquito, mamita.

Just a sip.”

My mother took a sip of the

coquito,

and a sip of beer and talked with her sisters. Little by little, she smiled again. My brother and I watched as she slowly regained her strut, her groove, her rhythm, and started laughing and greeting newcomers. Don Benny dedicated a song to her, and she pulled Don Agapito to the dance floor.

I couldn't believe my eyes. There she was, my mother, laughing and dancing again. After her eyes wanted to cut my father's throat! After she screeched so hard my chest wanted to explode! How could she be dancing right in front of my eyes, when an hour ago she was screaming and crying and pushing us out the door? What was that all about? My father most probably was at the house, or roaming around in his car, killing time, and alone like always. My mother was here, doing what she always did at family gatherings. Nothing had changed. All that anger and nervousness and pain for nothing!

I walked out of Don Agapito's terrace onto the street and went to sit in my Grandma's veranda. I was in no mood for Christmas Eve. Why should I be? I opened my purse, took out my banana-flavored lip gloss and looked at it for a moment. No messages sent, none received. So I opened the lip gloss and retouched my lips, feeling sorry for myself.

A while later, I saw my mother walking towards me with a smile. “There you are, I was looking all over for you,” she said. “Do you want an

alcapurria

? Doña Gladys is frying a fresh batch now.” As soon as I looked at her, my eyes filled with tears. I turned my face away, but she saw my watery eyes. Quietly, she sat very close to me and waited. I couldn't speak. So many words jumped to my mouth. I wanted to tell her she did not have to look at my father that way, even if he was a jerk sometimes. I wanted to scream that she shouldn't be so happy, that she should feel sick and confused and bitter, like I was feeling. But I couldn't speak. All I could do was feel my eyes swell with tears, hold my banana-flavored lip gloss and sit beside her. After a while, Mom spoke.

“Don't you worry. It was just a fight. People fight all the time,” she said.

At last my mouth filled with sound. I sobbed. “But parents should not fight, not on Nochebuena.”

“Who told you that lie?”

“Nobody fights more than Papi and you. That can't be right, Mami.”

“Maybe you're right. But that should not ruin your entire evening. Tonight is Christmas Eve.”

“I don't feel like waiting for Christmas anymore.”

“Well, you should. You should always wait for happier times. They won't come if you don't wait for them.”

“What if they never come, Mami?”

“Oh, they always come. You just have to draw them to you.”

“And how do you do that?”

“By laughing and dancing. At first you don't feel you want to bother, but all of a sudden a lightness takes over your steps. And there you go. You are happy again.”

“But that's only for a little while, as long as the music plays. But then the party ends and it's over.”

“That's all you need, sometimes, a little happiness to get you going. After that, you'll manage on your own,” she said as she looked at the sky.

My mother stayed with me a little longer. We looked at the stars, listened to the music, and sang along, sitting on Grandma's porch,

solitas las dos.

When we returned to Don Agapito's terrace, we danced together. I had a great time that night. I even drank some

coquito

that Grandma poured for me into a thimble. I got a little drunk, I think. At the end of the party, I gave Don Agapito a big smack on the cheek. It smelled of coconut, cinnamon, and rum.

“

Mira,

Mariana, this daughter of yours is a little tipsy,” he told my mother, laughing.

“

Adiós,

Agapito, what do you expect. She is a Febres girl.

Sandunguera,

desde chiquita.

She was born knowing what partying is all about.”

Tres Leches

CREAM CAKE

Our friend Luis Miguel RodrÃguez Villa gave us this recipe. It was created by his sister, MarÃa Cristina RodrÃguez de Littke, who won a contest sponsored by Puerto Rico's

San Juan Star

for the best

tres leches

on the island. When we tested it ourselves, we understood why this was the winning entry. It's a very simple version of a dish that can be very complicated to make, and it's sinfully delicious.

Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

Separate the eggs. Beat the egg whites until fluffy. Add the sugar gradually and mix well. Blend in the egg yolks, one at a time. Alternately blend in the milk, flour, and baking powder. Add the vanilla and blend well. Pour into a greased, square baking pan, and bake 45 minutes or until a knife inserted in the cake comes out clean.

Remove the cake from the oven and pierce it with a fork, making little holes evenly over the surface.

Set aside to cool.

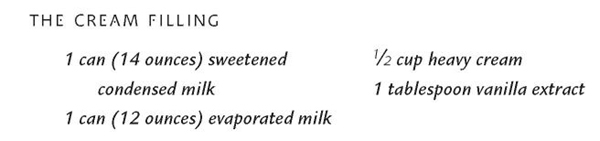

In a large bowl, mix condensed milk, evaporated milk, and vanilla extract until well blended. Slowly pour the mixture over the top of the cake.

THE FROSTING

1 cup whipping cream

Beat whipping cream until stiff. Spread over cake.

Makes

10

to

12

servings

Ray

Suárez

Ray Suárez grew up in Brooklyn, New York. The host of National Public Radio's

award-winning call-in news program,

Talk of the Nation,

he has been a reporter

for NBC affiliate WMAQ-TV in Chicago and CBS Radio in Rome, a correspondentfor CNN in Los Angeles, and a producer for ABC Radio Network in New

York. His work has appeared in the

Washington Post,

the

New York Times,

the

Chicago Tribune,

the

Baltimore Sun,

and other publications. He is the

author of

Running Away from Home

(Free Press), a book on white flight and

the American city.

NUESTRA NAVIDAD EN CHICAGO

A FEW DAYS before Christmas, the frost crawled up the inside of our old windows, making it harder to see the sidewalk below. Before we could wipe a window to get a glimpse of the park, an incongruous sound carried across the frigid, still air.

Two guitars, maracas, a

güiro,

and a small crowd trying to keep up with the songs were heading toward our house. The yellow glow of modern streetlights bounced off a brand-new dusting of snow. Our friends, laughing and threading their way across the whitened park, sent up little breath-cloud plumes against the bright light. Christmas was arriving in the form of these frozen musicians and their chilled chorus, and we could watch it all for another minute before running to open the door.

Usually by this time of year my wife and I would have long since made our reservations for the flight back to New York. Virtually every Christmas we had followed a star back to Brooklyn. From London, Rome, Los Angeles, or Chicago, we always managed, a few days before, on the eve, or unpardonably early on Christmas morning, when Kennedy and La Guardia are quiet as tombs. One relative or another could always be prodded into sleepily heading over the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway to pick us up.

This Christmas we were confined; my wife, as the King James Version would say, was “great with child,” our first. We had been renovating, as cash would permit, an eighty-five-year-old faded beauty facing a small park. Palmer Square was home to successive waves of Chicagoans since it was first developed in the early years of the century. The Norwegian, Swedish, and German petit bourgeoisie had given way to Ukrainians, Russian Jews, and Poles, and eventually to Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and a sprinkling of Latinos from clear down to Tierra del Fuego.

In the closing years of the 1980s, Puerto Ricans and, increasingly, Mexicans were buying and fixing small houses on side streets off the broad, beautiful boulevard that ran like a ribbon through the neighborhood. The houses had two or three apartments, making it feasible to split the mortgage with a cousin, brother, or sister.

Beautiful graystones, from the years on either side of the First World War, were available at prices impossible to find in other, more gentrified sections of town. So a new class of Latino yuppies, not scared of the neighborhood's Spanish-speaking ambience, began drifting in from the Lakefront.

There we were, often the first people in our families to head for college, pick up degrees, and march into big corporations. Sure, Latinos had worked down in the Loop for years, but they had been heavily concentratedâsome would say confinedâin the hotel and restaurant business.

At the same time, we were still who we were. Many born there, others born here. The Ecuadoran MBA and the Mexican-American real estate agent, the Colombian municipal-contracts supervisor and the Mexican-American not-for-profit manager, Puerto Ricans born here who spoke English with an accent, and Puerto Ricans born there who spoke Spanish with an accent. We were clustered in our late thirties, political, ambitious, angry, and affectionate.

We found each other, through the bush telegraph of political fund-raisers and community agency open houses and friendships formed in college. We sought out each other's company, babysat, shared bottles of wine, and sang “Happy Birthday.” Now it was Christmas. Somebody said, “How about a

parranda?

” We had all laughed.

Parranda

was a lovely custom, more suited to a low-rise tropical world of villages and small towns. It was a custom that might not be expected to travel any better than the

coquÃ,

the Puerto Rican frog said to die when it is taken off the island.

Musicians singing traditional

aguinaldos

would wander from house to house, expecting to find hospitality, both solid and liquid, at every stop. The

parrandistas

literally sang for their supper, accompanied by the householders and a growing entourage of friends, neighbors, and relatives, on- or off-key. It is a beautiful custom, quite in tune with that old and perhaps vanishing Puerto Rico, where people not only knew all their neighbors but all their neighbors' business, as well.

In late-twentieth-century Chicago, we had to find a broader definition of kinship. We were amalgam people. Our

parranda

would meld the warmth and welcome we believed was our birthright with the caution of the new proprietors we had struggled so hard to become. Not everyone who decided they'd like to join in would be welcome.

There would be more surrenders. Now thirty-eight weeks pregnant, there was no way Carole was going to cook the labor-intensive dishes of the season:

pasteles,

mashed plantain stuffed with pork;

pollo guisado,

chicken and vegetables in red sauce;

pastelillos,

fried meat pies. No, these would beâsorry, Abuelaâbought from Sabor Latino, one of a cluster of struggling, undercapitalized, and occasionally wonderful small restaurants in our neighborhood.

Invitations were spit out of desktop-publishing programs. Homes were decorated. Food was ordered. Booze was acquired. A few days before the party, a cold front came barreling down from Canada, promising to make this one of the coldest Christmases in a generation. Perfect. Just the thing to remind us we weren't on the island anymore.

Phone calls followed. Should we move from house to house? Should the pregnant women (three of them) go by car while the first ever Iditarod

parranda

proceeded by snowshoe? We stuck with our plan. A frozen delivery man from Sabor Latino arrived an hour later than expected, but before the guests (also late) arrived from their first stop around the corner.

Candles were lit. Lights dimmed. The house began to fill with the bouquet of vast amounts of Puerto Rican food. We stood by the frosty windows and waited for the bell. Leaving the door open was out of the question in single-digit cold. Musicians and revelers and, yes, even pregnant women climbed the stairs, their faces flushed scarlet and their eyes shining. The songs continued in the living room.

The Anglos scattered through the room, friends, neighbors, spouses, and lovers sipped their drinks and smiled indulgently, some limbering up their high-school Spanish and consulting the song sheets, drinking the whole thing in. This is what the potent combination of migration and education brings.

It was a cornerstone belief of the Latinos in the room that something beyond merely liking each other bound us together. We looked for the similarities in family histories, the struggles of the newly landed, and our ongoing argument with America about being here. There was the bond of religion (though many were indifferent Catholics, even outright atheists). There was the bond of Spanish (though there was a range in facility from poetic fluency to something hard on the ear). Time in the States ranged from a few years to a few generations to South Texans who had been in the country as long as there had been one.

Yet somehow we were all

raza.

More sentimental than hardheaded? Maybe. Was this notion of identity so plastic we could easily bend it to fit our needs? Perhaps. But here in this city so far from the places where the Giraldos and the Laras and the MartÃnezes and the GarcÃas and the Suárezes started their journeys, we didn't need to analyze all this very much. We saw ourselves in each others' eyes, and that was enough. For those of us far from home and the people who shared our names and our DNA, this was as good a family as we could find on the road. For this holiday, we had created a warm country to live in. It was Christmas in Pan-America, and though there would never be a special on TV for our new nation, we had a feeling we were all on our way to a different somewhere than the place where we started out.

Pitorro,

a Puerto Rican grappa found more often in well-washed plastic bleach containers than in fancy bottles, emerged from someone's coat. Despite a hurried life, I found time to make pitchers of

coquito.

The songs continued. The Three Kings on the mantel stared across the living room at the silently winking Christmas tree.

When the

parrandistas

made their way to the next house, we took a deep breath. Alone again, we began to clean up. After bouncing around a lot through our married life, we were home. We cared about these people, and were happy to have a house full of them.

Late on El DÃa de los Tres Reyes, the contractions began. I packed away the Christmas ornaments while Carole labored, knowing that soon there would be very little time for these chores. The deep chill had kept its grip on Chicago through Christmas and into the young New Year. We drove through quiet, cold streets the next morning to the hospital, and Rafael was in our arms just a few hours later. He was too late for the party, and right on time.