Language Arts (9 page)

Authors: Stephanie Kallos

“A person could live in this room, practically,” Pam observed.

This was exactly how Charles felt, but this concurring remark from his colleague was disturbing, especially since there were in fact many times when he'd opted to spend the night here. What if Pam Hamilton got it into her head to do the same? They all had master keys.

“Do you mind if I sit for a minute?” Pam went on. “There's something I wanted to talk to you about.”

She eased down onto the sofa so that they were facing each other across the room's expanse and took a sip of whatever was in that atrocious mug.

“Have you seen Romy Bertleson today?” she asked.

“Yes, she's one of my homeroom kids.”

Pam had an understated, unfussy elegance: no makeup; a nimbus of curly, blond, flyaway hair generously scribbled with silver and battened down on either side of Pam's face (just barely) by a pair of tortoise-shell combs; wire-rimmed glasses; boyish figure; khakis and a cardigan and slip-on Merrells. “She's changed, hasn't she?” Pam said.

“God, yes.”

Pam had been at City Prana as long as anyone; she and a group of young parents/educators had started the school back in the 1970s. All three of Pam's children had gone here. Now she was a grandmother.

“Don't you love it? When kids transform like that?”

Not really,

Charles wanted to say.

Pam absent-mindedly fingered her multistranded, multicolored necklaceâbeads and carved stone, animal fetishes (Alaskan, was Charles's guess; he remembered that one of her daughters lived up that way)âthere was something rosary-like about it. Charles wondered from time to time if Pam was another lapsedâor even practicingâCatholic. Not that they discussed personal matters.

“Have you had a chance to speak with her about her project idea?” Pam asked.

“Not yet, but she turned in a rough draft proposal.”

“Have you read it?”

“Not all of it.”

Staring at the contents of her mug, Pam raised and lowered her tea bag a few times. “I don't want to steal her thunder. She'll tell you about it.”

Charles glanced at the clock. “Well . . . ,” he said, hoping the up-inflected word would have the effect of lifting Pam off the sofa.

“I just wanted to make sure it's okay with you.”

“Sorry; whether what's okay?”

Pam looked up. “Romy's proposal? Art Without Boundaries? Her taking photographs? That's not an issue for you?”

“Why would it be an issue?”

“Well . . . Cody participates in that program, doesn't he?”

Charles was surprised that Pam knew this, but then he remembered that she and Alison had stayed in touch after the divorce. Ali had probably mentioned it.

“Yes. He goes to classes twice a week.”

Clearly, Pam was waiting for him to elaborate, but what else was there to say? He certainly wasn't going to object to Romy's proposal because it would put her in contact with his son. Was that what Pam was worried about?

“How is Cody doing?”

“Fine.”

Charles avoided her eyes; he became entranced by the way she continued to raise and lower the tea bag, rhythmically, precisely; it was like watching a miniature offshore oil-rig operation.

“Okay, then,” she said finally. “One more thing . . .” She withdrew the tea bag, tossed it into a nearby receptacle, and settled back into the sofa cushions with the demeanor of someone intending a long visit. “Because Romy's including both art and creative-writing elements, I think she's going to ask us to be co-advisers.”

“What? Why? I mean, it's not something I've been asked to do before.”

“I have, by other kids with dual-focus projects. There are advantages. We can share the load.”

“True,” Charles said, although he had no idea how that would work.

“Do you have her proposal? She's got something in there about people without language.” Pam looked at him expectantly.

Charles turned over the proposal and began leafing through it. “âWho tells the stories of people who have limited or no language? Is there a way to help empower such people to tell their own stories?'”

“Good stuff, don't you think?”

Charles grunted in the affirmative but he was mostly thinking about how much he hated (

despised, disdained

) the word

empower.

“She's got this kind of Diane-Arbus-meets-Dorothea-Lange-meets-Allen-Ginsberg homage going on, unconsciously, I think, and obviously derivative, but you know what they say: Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.”

A child who cannot imitate cannot learn.

The response was so ingrained and automatic that Charles thought it was subtextual, but when there was a silence, he looked up to find Pam staring at him again, and he realized he'd spoken aloud.

“Right,” she said flatly, and stood. Her thin figure seemed older now, stiff; her movements contained a quality of angularity, like a card table being set up, or an ironing board. “Well, let me know how it goes with Romy and what you decide about the co-adviser thing. Have a good one.”

After she was gone, Charles left his desk and began moving through the room, feeling compelled to touch the desks, tidy the books, re-angle the folding screens, refluff the sofa cushionsâin reassurance, perhaps, or to reinforce his proprietary relationship to this sanctuary.

The upholstery was lightly scented with whatever Pam had been drinking, something herbal and spicy. The smell reminded Charles of the ginger-molasses cookies that were a daily staple of the Cloud City pastry caseâand Emmy's favorite.

He must remember to buy some and send a care package soon.

â¢â¦â¢

By twelve forty-five, Charles's exchange with Pam Hamilton had been excised from his awareness. He'd closed the door to his classroom, had eaten some soup, and was hunkered down in one of the beanbag chairs reading Ted Kooser's

100 Postcards to Jim Harrison

when someone knocked.

He jerked the door open to find Romy Bertleson. Wide-eyed, she took a half step back. He'd frightened her.

“Hi, Mr. Marlow,” she said in her high-pitched, scratchy voice: Tweety Bird with seasonal allergies. “Sorry to interrupt. I was wondering if you had time to talk . . .”

Although his hospitality was a lieâhe was still struggling with an overwhelming feeling of just not being

ready

for all thisâhe said yes, of course, invited her to come in, left the door open as protocol mandated, and assumed a seat behind his desk.

“Did you get a chance to look at my proposal?” Romy asked.

There was that smell again: citrusy, lush, confectionary, complex.

“I did, yes, but . . .” Charles hastily retrieved Romy's paperwork. He remembered now that she'd asked him at the end of homeroom if she could stop by during lunch; he should have been prepared. “Why don't you tell me more about what you have in mind?”

And so she began, a scatter shot of words, enthused, heedless, optimistic, in that wonderfully unguarded way that belongs to the impassioned young, telling him that the only thing she'd settled on for sure was the idea of creating photographic portraits paired with some kind of text, maybe poetry. She mentioned the unit Charles taught in tenth grade, Allen Ginsberg's American Sentences: seventeen syllables, haikus unspooled.

“I'm not a poet, not like . . .” And she named a few classmates, young people Charles knew to be connected with Seattle's poetry-slam scene and whoâCharles could only guess, for he'd never actually

been

to a poetry slamâlikely shouted amplified obscenities with a rapturous sense of discovery, ownership, and invention, as if Lenny Bruce had never existed. But that too Charles found charming and worthy of commendation; at some point, he imagined, the trend would swing in the opposite direction, and notions of what was radical would involve unplugging and reciting hymnic poems, as if Emily Dickinson had never existed.

“But American Sentences,” she continued, “I like those, and having the creative-writing component would be a way of stepping outside my comfort zone, like we're supposed to. That's why I was hoping you'd be a co-adviser with Ms. Hamilton.”

She fell silent and blinked several times, re-agitating the air and sending a satsuma-scented squall in Charles's direction. She'd been talking for so long and with such run-on patterned inflections that it took him a few moments to realize that some sort of query had been posed and she was awaiting a response.

“You've obviously given this a lot of thought,” he said, buying time by stating the obvious.

What had she asked? He looked downâHad her eyes always been this huge and luminous? Had she always looked so much like Emmy?âand shuffled through her proposal. “You said something about having a personal connection to your project . . .”

“Yes.” She swallowed hard and readjusted her position, sitting back, crossing an ankle over her thigh, a habitual posture that didn't carry its former cockiness since she held her hands in a demure, meditative fashion: two small nested bowls, precisely placed in the center of her lap. “My grandma had Alzheimer's. We used to be really close until she got sick. She died over the summer. Toward the end, she didn't know any of us, not even my mom, and . . . well, I'm just sorry that I didn't find out more about her, and about the disease, before it, well, took her away from us.”

Here then, Charles understood, was the deeper circumstance beneath Romy Bertleson's transformation.

Sometimes,

he thought,

they really do flower

right before your eyes.

“I'm sorry,” he said, recalling that blooms do not always emerge in sunlight but can be

forced

by prolonged darkness and isolation, by sorrow.

Charles paused, waiting to see if Romy had more to divulge. Or ask.

She didn't, andârecognizing a fellow tortoise when he saw oneâCharles made no further attempt to invite her confidence. In his opinion (one in opposition to the current trend), teenagers had just as much right to hide within a carapace of privacy as adults.

“I'd be happy to be your adviser,” he said, “along with Ms. Hamilton.”

Romy's eyes widened brieflyâa toddler on the playground swing getting pushed just a little too highâbut then she frowned and stared down into her upturned palms with such intensity that Charles wondered for a moment if she'd been conducting the interview with the aid of crib notes.

“Just get on the paperwork,” Charles continued, rising from his desk and ushering her toward the door. “I know it's a pain, but it's the way we do things.”

“Thanks, Mr. Marlow.”

Suddenly shedding her diffidence, she stood up straight and readjusted her camera in a resolute manner that made Charles afraid she was about to shoot his picture at point-blank range.

But she merely added “See you tomorrow!” and then clumped away on those heavy clog-like shoes with the urgency of Dorothea Lange on a deadline. Teenagers could be such chameleons.

Charles checked the clock: seven minutes until the bell.

After closing the door, he crossed the room and sank back into his beanbag chair, intending to resume reading. But he found that he was too distracted by shafts of light and shadow bending and crisscrossing as they fell between the satsuma trees.

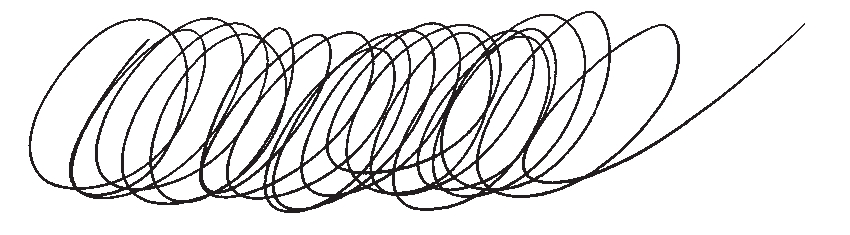

Once in a while you might notice an elderly personâor even someone of my father's generationâdoodling a long series of loops like this:

Try it. It's harder than it looks.

I said

doodling,

but it's the wrong word, implying as it does a kind of mindlessness, an absence of awareness and intent, a physical correlate, perhaps, to

daydreaming.

A more accurate verb would be

producing.

This will serve as your introduction to the handwriting system known as the Palmer Method. We'll begin with basic loop practice.

What you're aiming for is threefold: a perfectly smooth line, uniformity of loop size, and evenness of pen pressure. (A superior writing implementâmy father's Montegrappa Italia, for exampleâis a great assist in this regard, by the way.)

All of this requires maintaining a balance between control and relaxationâa challenge in

any

endeavorâand to this end, finding the right speed is both a vital part of the process and a highly personalized one, since most human beings move through life in a predetermined metronomic comfort zone. Going too fast will lend a frantic quality to the experience; going too slow will make one feel clunky, impatient, stalled, uncalibratedâa cog out of whack, a set of misaligned zipper teeth. One person's largo is another person's allegro

,

so when it comes to tempo, do not expect to succeed by emulating someone else, not your penmanship teacher, not a fellow student, not even that amazingly proficient little woman sitting in the Madonna's Home waiting room. Success in the execution of Palmer loops demands that you locate the beat of your inner drummer.