Lamy of Santa Fe (50 page)

Authors: Paul Horgan

Archbishop Lamy lying in state in the Loretto Chapel of Our Lady of Light, night of 13 February 1888

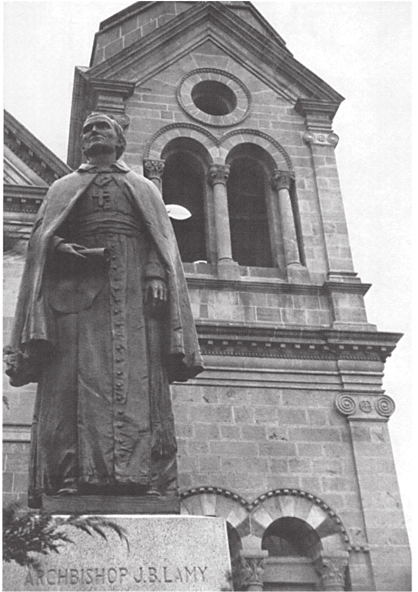

Statue of Lamy in front of his cathedral in Santa Fe, which was unveiled in 1915. Willa Cather thought he looked “well-bred and distinguished⦠there was about him something fearless and fineâ¦.”

Machebeufâlike Lamyâcould readily countenance the common longing of people for material things. It was an energy which given opportunity worked toward commercial civilization. As powerful was that other energy which called for the unseen spirit of men and women to be given visible form. Once again in an alien place Machebeuf went to work in its behalf. Before a year was out, he wrote to his brother Marius,

Since you are the head of the family, I send you this little sign of life to give to all the others.⦠Here I am, firmly established at the foot of the Rocky Mountains (at least for a while, as I don't know where I'll die). This evening I leave for my eighth trip across the Middle and South Parks. N.B.: consult a map and follow me if you can, even though I have to cross the highest range several times to visit our poor Catholics, who are almost buried alive in the depths of the mines. I am very well. Providence has given me strength according to the need. To get to California Gulch, which is on the western slope of the mountains, I often have to sleep under the stars, sometimes surrounded by snow, as in last July, but thanks be to God, I sleep there as soundly as in a feather bed. Besides the principal parish, established at Denver, we have begun another in the center of the mountains at a flourishing place called Central City. I go there next Sunday to say Mass for the first time in our temporary church [it was the hall of a lodge called the Sons of Malta]. After several days there I'll go on to South Parkâand from the crest of the Snowy-Range (or chain white with snow) I'll be able to see through the gorges far off the territory of Utah where the Mormons live. I'll be returning only at the end of September [1861] to pass a few days at Denver and Central City, and then, in October, I'll move on again to the same South Park, and New Mexico, Santa Fe, and Albuquerque [

sic

] & after procuring some vestments which the nuns are busy making, and some good Mexican wine for Mass, and for the table now and then, I'll return to Denver by Christmas at the latest.

“Father Machebeuf,” observed Lamy, “seems to be in fine spirits.”

vii

.

Marie, the Convent, the Country

W

HEN MARIE LAMY

came to her uncle at Santa Fe in 1859 she was a “parlor boarder.” At sixteen, she gave herself airs, tossing her freshly laundered collars back to be washed again if they did not suit her. The convent suffered herâshe was lovely, she was the bishop's niece, and there was that moving within her which led her to become a postulant on 1 October 1859, two years after her arrival. She wore silk dressesâthis was remarked uponâbut even so, she never shirked her duties, however unpleasant, for they included the responsibility of cleaning the outdoor toilets. When Lamy received her into the first stage of the sisterhood, he was proud. She assumed the name Sister Mary Francesca. With her addition, the membership of the Loretto convent reached twenty-six. There were those among them who eventually came to think of Sister Francesca as a saint. One who grew to a great age kept all her life a towel with Francesca's name on it. The lovely child from the Ursulines was growing into a remarkable maturity.

“Our little schools are on the increase,” Lamy had said in 1859, “we have at least two hundred children, between boys and girls.” What he had to offer was being eagerly taken, and the nuns were pleased to present their curriculum of “Spanish grammar, English, French Reading, Orthography, Spanish Geography, Maps, Spanish and American History, Pizarro's Dialogues, Mythology, Copybook Penmanship ⦠Piano, oil painting, crocheting, and”âwhat appeared to be an especially nun-like craftâ”embroidery on perforated paper.”

If parts of the course seem mystifying, occasionally there was more in the convent by which to be both mystified and edified, as in the case of Sister Hilaria and the Devil. It seemed that Mother Magdalen, in order to improve the instruction in piano, which was in the charge of Sister Hilaria, engaged a professor of music to teach her the art, in which she “showed much promise.” As a matter of course, she was always chaperoned by another nun, usually Sister Filomena Lujan, when the professor came to the convent to give the lessons. Both sisters were young, and Sister Filomena did not understand English and so

missed certain meanings in the remarks made by the musician to his pupil, who, young as she was, also did not take what was meant for what it wasâan infatuation on the professor's part. “One day he asked her to go to a concert being given in the town and she asked and obtained the permission. The Professor called in his carriage for Sister Hilaria and her companion.” An appalling revelation then took place. “As she was about to enter the vehicle, Sister Hilaria looked down and saw cloven hoofs where the professor's feet should have been.” As fast as she could she turned and followed by Sister Filomena ran back into the convent.

To think

â! It was an inexhaustible subject within the walls. Changing her name to Sister Rosanna, Hilaria never again left the convent.

It was gratifying to Loretto that “a smart and fine young lady,” the heiress of one of the richest native families in New Mexico, entered the order. Lamy remarked that her father and grandfather “could beat the patriarch Job for the number of stock, out of the increase of their sheep, they have sold upwards of seventy thousand heads in few years ⦔ When she died some years later, she left her property to the nuns, and her will was contested by her family, but was finally upheld by the courts. By 1861 there were over three hundred pupils in Lamy's schools, and it was plain to see that the holy training of the children had its good effect on their parents also. The convent property was being improved through the yearsâ”Our place is beautiful,” said Mother Magdalen, who had assumed her unknown responsibilities on the bank of the Missouri in 1852, “everybody says there is not another such in the Territory.” A wall was built around the grounds, the trees grew so tall that they could soon be seen from a great distance, water flowed in acequias to the flower and vegetable beds and Sister Catalina was kept busy in the garden. To add to the convent fruit trees, Machebeuf brought oranges from the West in 1860.

A year before the arrival of the Christian Brothers with Vicar General Eguillon in 1859, Lamy had made ready for them, asking Rome to let him exchange certain pieces of church land so that he would have a convenient place in which to receive the Brothers and start their boys' school, which would grow in its educational reach until it became a college named after St Michael the Archangel (and which long later in an act of administrative expediency changed its name to the College of Santa Fe). When they arrived the Brothers must be content with “an adobe hut with four walls,” five mattresses, five blankets, two tables, a few benches and some old carpets. They were invited to share Lamy's table until their own kitchen should be ready. The bishop presented them with a contract, assuming all their debts until they should become self-supporting, paying them eight hundred dollars a

year, and perquisites including board and laundry. The contract specified that for breakfast they should be fed bread, meat, and coffee; for dinner, bread, meat, vegetables, dessert, and on occasion, wine. Within a month of their arrival they were open for enrollment, took in at once thirty boarders and more than a hundred and fifty day scholars. It would be, thought Lamy, a “pretty good school.” The Santa Fe newspaper took pleasure, daily, in seeing what had never been seen there before: “the cleanly, joyous little fellows, going and coming from the place”âthe school stood next to San Miguel's, the oldest church in Santa Fe and probably in the nationâ”where they receive the seeds of instruction, from which shall grow the future rulers, teachers and business men of New Mexico.” Lamy would have the school grow, and asked Purcell to procure him a loan of “four or five thousand for five years.⦠I have got good property to answer for it” as security. Above all, he kept urging, the great need for a seminary remained.

But even if matters moved forward in the long view, there were setbacks. In 1861 a smallpox epidemic greatly reduced the school enrollments, and an outbreak of Indian troubles (so dreadful that Lamy called it “war in the west”) endangered the daily life of the territory. The mail service, monthly until 1858 and weekly thereafter, and all other communications, were cut offâeven the Army received no official papers from the government. Twenty men were killed at one mission, where sheep, cattle, and other supplies were stolen. Citizen volunteers mobilized to fight the depredations. It was, said the bishop, “a reign of terror.” A speculative soldier decided the Navajos were descended from Welsh families cast away long ago on the Texas Gulf Coast. “Persons,” he said, “who speak the Welsh language find no difficulty in understanding them and being understood by them ⦔ Such interesting knowledge did little to help the general situation, which was even more difficult because of the effects of a drought which for three years had held the country. Produce was scarce, prices “were frightful”âso high that many poor people were in great want, said Lamy. Increased illness of all sorts kept reminding him of the need for a hospital.

Meanwhile, the routine of his officeâadministrative affairs with Rome, and now Denverâkept him at his desk for long hours when he was not out on the dusty highways to the remote missions.

He seemed to ignore his none-too-robust health, but there were moments when it failed him. In 1859 he had fainted at the altar while saying Mass on the Feast of SS Peter and Paul in the convent oratory. Mother Magdalen was present. During the Epistle she heard a great noise and looked up. The bishop was not in sight. She ran forward. He was lying unconscious, face upward, across the top step of the altar.

She tried to raise him but could not, and then ran to fetch camphor. By the time she returned, some men had lifted him up. He regained consciousness and sat down for a little while, bathing his hands in cold water; and then, “though with difficulty,” he completed the Mass. Afterward he drank a little coffee and was helped to his house. “You can imagine,” noted Mother Magdalen, “better than I can describe what I felt on seeing his Lordship prostrated in his vestments as though dead.⦔

Within a short while he was writing as vigorously as ever to Barnabo pursuing the elusive decision on the Gadsden Purchase. His life continued in Spartan simplicity, and one time on returning from his little ranch four miles north of town where he had been ill, he found that the Mother Superior had installed a stove in the chapel where he said Mass, the better to keep him warm. It was instantly removed when he said that “if he was to say Mass there, that stove should be taken out.”

But he knew, too, when to provide warmth and gaiety himself for his helpers, and after school term in 1860 invited the nuns and others to a picnic at his

ranchito

, thirty-two of them. They took their lunch with them, some sat on the floor of the little two-room stone cabin where he had already planted trees by the porch. Nobody was left to take care of the convent but “the little musician Francis.” Lamy loved the country and stayed several days after the picnic.

At his desk, he conducted his entire correspondence by himself until very late in life. Always clear and deliberate, changes in his handwriting reflected the labor and the passing of the years. Routine reports (there was still opposition, though lessened, among some of the native clergy); finances (he regularly consulted Purcell about business plans and when he had to borrow from him said he would rather help Purcell than ask for help); regular, if modest, payments of Peter's Pence to Rome; whenever possible repayment by installment of his debt to the Society in Paris by requesting them to withhold what he could afford to spare from their annual allocation to him, which was for him “a great pleasure.”

After ten years of struggling with the tithing regulations, he wrote to Cardinal Barnabo: “Here the principal revenue of the church comes from the tithe. A good number of worshippers give it reluctantly and almost never completely; an even greater number refuse to give it at all. All this makes the administration very difficult. Could we be authorized to change this custom and to adopt rules more suited to our present circumstances, after having consulted our clergy on the matter?”

Meanwhile, to the delight of all, Santa Fe's old customs continued,

such as the manner of celebration on great occasions. On St Francis's eveâhe being the patron of the old New Mexican kingdom and the cathedralâLamy recorded: “about sundown, first vespers,” then “grand illumination in the whole town, made with small piles of pine wood on the top of every houseâthe poorest families will have several piles, on the roof of the Cathedral we will have not less than forty fires. We are ignorant of the use of fire-engines. I never witnessed here a house on fire for our buildings are fire proof”âLamy's first admission of any value attached to the old earthen architecture of New Mexico.