Lamy of Santa Fe (24 page)

Authors: Paul Horgan

Comanches knew the road well and, working out of their retreat in the Bolsón de Mapimà to the east (a great purse-shaped desert valley

roughly 150 miles long and 100 wide), had their way with passengers who had no refuge. Where there was an occasional ranch, it was centered on a hacienda built like a square fort, with sentries on the flat roof, and marksmen's portholes, and a great timbered double doorway bolted and barred every night. Once accepted within, travellers were treated to good food, ingenious song and dance accompanied by guitars, and even folk plays in pantomime. By day men worked in the close-lying fields, while women cooked or sewed; but an Englishman passing by such a wilderness lodgement remarked that “severe labor is unknown to either men or women.” The United States citizens who had taken Mexican territory north of Chihuahua were known locally as “the barbarians of the North.”

Lamy met a continuing sequence of land forms as he went. In effect, all of that Mexico which he travelled was a vast repetition of land which in many ways resembled New Mexicoâthere was a great terrestrial rhythm which repeated mountain, desert, and river course (whether wet or dry), which he crossed innumerable times as he rode. Such a sequence of land supported a great variety of animalsâthe grizzly and brown bears, big-horn sheep, elk, many kinds of deer and antelope, the peccary, rabbits, and the wolf, and the coyote who sang dolefully at night. He could see fantastic birdsâthe

paysano

or chaparral cock, the great cranes of the sand hills, quailâa wonderful variety of insects, including the centipede, and the tarantula; and the rattlesnake, the copperhead, the horned toad, and the scorpion “whose sting, was sometimes fatal to children or,” noted the Englishman with originality, “persons of inflammable temperament.” Where anything grew from the ground, it was likely to be the mesquite or greasewood, unless near a ranch or in a wet arroyo a few willows or

alamito

âlittle cotton-woodâwere to be seen.

With human habitations so far apart, it was occasionally reassuring to see in the distanceâwhich diminished so slowlyâan occasional wayside chapel, with a tiled dome, pink or blue, and a corner tower, and a frame of trees; and yet seen more closely, it would show a black cavern of an open door in its ornamented plaster front, the doors awry on their hinges, or thrown down, and within, drifts of desert sand and cracked wallsâthe work of such Indian people as never stayed, but who must destroy the works of strangers on the land.

It was a welcome, if implausible sight, in that vast vacancy, to discern at last, two hundred thirty miles south of El Paso del Norte, the city of Chihuahua, which lay against dust-colored hills. It was built on rolling land, and its Spanish aqueduct, with its “stupendous arches,” whitewashed houses, and the towers of its churches and its reaches of trees rising from patio gardens under the pitiless sun, made it seem

larger than it was. Not as old as Santa Fe, it had a population of perhaps ten thousand. It was the most considerable town of northern Mexico, where trade routes converged from New Mexico, Sonora, and California, and where silver from thriving mines in the sierra to the west was hauled into town. What was known as the Santa Fe Trail, which began at Independence, Missouri, actually ended in Chihuahua, with Santa Fe as a midway point. A merchant city, Chihuahua was twelve hundred and fifty miles as the crow flies from the capital city of Mexico, but even in its isolation it had been reasonably well sustained by the viceregal government of Spain. Since the independence of Mexico, the city had been left more or less as a wilderness outpost, to live on its own resources.

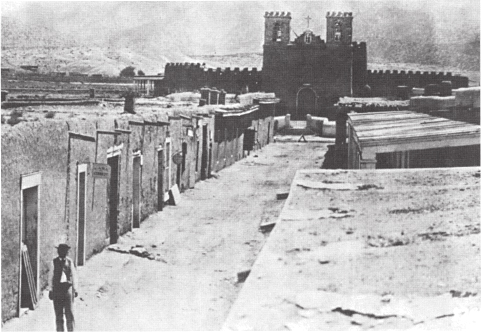

Lamy rode into town through streets laid out in squares, unlike those of Santa Fe, which had seemed to follow the trails of animals seeking the meagre watercourse of the Santa Fe Creek. The houses of the Chihuahueños were of adobe, but many were cornered and corniced with cut stone from the dusty hills about. At the center rose the cathedral, with its towers over a hundred feet tall, whose bells marked the many services of the day. The great bell, said a Santa Fe trader, could be heard at a distance of twenty-five miles. Lamy could see that the façade of the cathedral, which the English traveller said was built “in no style of architecture,” displayed niches which contained life-sized figures of Christ and the twelve apostles. Behind the grand façade was an interior which bore “striking marks of poverty and neglect,” Across from the cathedral was a

portal

or portico running the whole length of one side of the plaza. It was the habit of the residents to string along the

portal

roof the scalps of raiding Indians which had been taken by hunters paid by the local government. Not long before Lamy's passage through town, one hundred and seventy fresh Apache scalps had been paraded through the streets by a procession of men, women, and children. The display was a daily reminder of what a journey away from the protection of the city might mean. Americans and “Northerners” were not warmly welcomed in Chihuahua eitherâthe Chihuahueños, from the governor on down, still remembered “every class of excesses” committed against them by the invading army from the States in the recent war.

Lamy now had five hundred miles left to go across the open country. In long stretches the road became a trail which was at times hard to follow. Having crossed mountain, desert, valley, in the familiar sequence, by now he had become a plainsman who knew how to watch for features of the land which would serve Indians as hiding places. Space and silence and pouring light by day; and sometimes in optical illusions the strange, imagined presence of savagesâa species of cactus

which had a thick body and stood at about the height of a man, crowned with spikes which at certain distances and lights looked startlingly like an Indian with a great crest of feathers. By night, under the stars, a sense greater than ever of the vastness of the land and its emptiness, and its silence, until the long cry of the coyote came over the distance; or, nearby, the obscure crackings and rattlings of shelled insects alerting the ground sleeper.

He passed the small town of Camargo, where the church was distempered in pale yellow, while its tower was rose-pink and the dome over the sanctuary a faded blue, all against bare rock mountains in the distance. There were hardships and glories in the weatherâsometimes came storms which seemed as wide as a continent, the airy equivalent of the desert reaches in size; and then the riders took shelter beside their horses. Again, there were storms of light itself, breaking through clouds above mountains, and standing rays of gold air against distant blue, and trailing far veils of rain which often never reached the ground but seemed to become part of the very light itself; and infinity, perhaps even eternity, had an image.

Coming to a settlement days apart from any other, the traveller might find himself in the midst of an alarumâIndians had been sighted and lost and seen again, and the hacienda within its fortress limits was a turmoil of action, as the master and all his household prepared to resist attack. Animals to secure within the walls; children to put safely away; food to be cooked and stored by the terrified women; water drawn; weapons cleaned and loaded; prayers recited; farmers called in from the fields; and then the long wait. And if it was a needless scare, then what followed would be relief expressed in festivity, with music and abundant food dipped with tortillas out of common bowls and all hospitality for the harmless stranger. He found the ways of the house much like those of Santa Feâsome furniture left over from the Spanish centuries, and some from memories of the Moors.

If Indians did not come, traders sometimes did, and then the household spent hours going over goods, bartering for stuffs, pulling silver pieces out of buckskin

bolsónes

to buy utensils or pretty trifles. Everyone had stories to exchangeâodd weather, escapes from Indians, good advice as to landmarks and passages for anyone travelling alone, locations, and of these, like the Arroyo de los Indios, where the rider might find enough water, caught in deep places, and cool, and perhaps shaded by a high bank from the hot sky, where he could pause for a bath, even then keeping watch for those after whom the arroyo was named, for they had made a trail which crossed it.

It was a land rich in minesâthe road passed through Hidalgo del Parral, where pale tailing lay against the slate-gray mountains from

which the ore was taken. The village had a three-tiered bell tower rising above its small, square adobe houses which were washed in many different colors. Durango state was a center for iron mining. If Parral seemed like an outpost of Durango city, it was not quite halfway there from Chihuahua.

But still the days passed in long thought and patience, and finally Lamy came to the hacienda of El Chorro, where there were salt licks for the horses, and lodging. There the news, along with that of vigilance

“por las novedades que hay

(for the troubles about),” was that Durango lay only twenty-eight miles further, beyond the corn fields where the great sand-hill cranes flew making their strange hoots by day or night.

v

.

Confrontation in Durango

L

AMY CAME ACROSS

the arid plain which surrounded Durango, and, through the formal grid of the streets which were arranged according to the uniform plan for colonial cities issued through the centuries by Madrid, found his way to the bishop's palace. This was a long, low building with plaster walls washed in pink. The façade had strength and eleganceâa cornice, window frames, footing, and a main doorway carved from an ochreous gray stone. The windows and the main entrance were barred with iron grilles. A stone cross surmounted the entrance, whose double doors were made of heavy wood, richly carved, in which a lesser, single door could be opened for inspection and inquiry, and closed for dismissal. Through the little single door a great patio was visibleâthe palace was built about a grand inner square where trees grew and a running portico hung out from the walls as protection from weather. From without, the building was inscrutable. In its general design it was not unlike the 1610 palace at Santa Fe; but it had an air of greater majestyâspoke of a finished style nearer the center of affairs; and in fact Durango was the northernmost extension of Spanish Mexico proper. All that lay above it on the map might as well have been a colony lost in distance and trifling in value. Lamy, his five-week journey ended, asked to be admitted to the presence of Bishop ZubirÃa.

José Antonio Laureano López de ZubirÃa y Escalante had been bishop of Durango for twenty years. He promptly received his visitor, and confronted a lean young man about half as old as himselfâZubirÃa was seventy years of age, having been born in Sonora in July 1781. All he knew of Lamy were a certain letter he had received from him months before, and various rumors abroad during the pastoral visit to the northern provinces in the previous yearâZubirÃa's third such tour, following the first in 1833, and the second in 1845. He knew well the country across which Lamy had just travelled, though ZubirÃa himself had not done it alone; had gone, in fact, with a heavy escort, which was wise under the prevailing conditions.

The old bishop received the younger with every kindness. ZubirÃa impressed others with his benevolent and intelligent expression. His face was fleshy, his hair dark, his eyebrows strongly marked above black eyes which had a narrow Mongolian slit to them which suggested the typical Mexican admixture of Indian blood, and also a reserved shrewdness. His nose was long and slender, above a wide mouth which in repose was turned down at the corners. In his age, his body was heavy, with a full throat which rolled over the edge of his frilled jabot. He loved to talk, his affability and grace of manner were remembered, and he had the reputation of a conscientious prelate much concerned for his people and his duties. He recalled with gratitude the official courtesies given him in his recent New Mexican visitâthe military escorts, the great public reception, crowds unable to obtain entry in the churches where he preached.

Despite the United States victory in the 1846 war he had never expected what was made known to him first by rumor, then by Lamy's letter of 10 April 1851 from San Antonio. On the contrary, he, with other bishops of the Mexican North, had been expressly ordered by Rome to continue their jurisdiction over the full extent of their original diocesan limits despite a new political boundary.

Charm and courtesy were his natural responses, and so, as the years would make plain, was a legalistic stubbornness concerning his responsibilities. He and Lamy had matters of common experience and light courtesies to exchange, but Lamy had really only one mission of immediate importance which had brought him to Durango. If Lamy had come prepared, ZubirÃa was no less sure of his own ground, and he had one further issue to raise with his visitorâand with Rome. First, however, he saw to the comfort of his guest, establishing him in the bishop's palace.

The crucial exchange of information followed. When Lamy's Spanish was inadequate, they conversed in Latin. ZubirÃa had written to Lamy on 12 June, in reply to Lamy's letter of 10 April from San Antonio.